S4E17. Balkan sombreros

Under the influence of films imported from Mexico, the Yu-Mex musical trend exploded in Tito's Yugoslavia. Fernando Martín Velazco traces the journey in search of these unexpected Yugoslav mariachis

Dear reader,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter with blurred boundaries.

Mariachis, sombreros, ¡Que viva México!

What all the Mexican stereotypes have to do with the Balkans? Well, there was a time when the melodies of the deepest rural areas of Western Mexico could also be heard in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and in all the other former Yugoslav countries.

It was called Yu-Mex (from ‘Yugoslavia’ and ‘Mexico’) and was one of the most important musical and cultural phenomena in Yugoslavia for a limited period of time.

This genre originated from the exchange between two countries that were geographically far away, but at the same time united by the same need to build a myth of national unity and identity rooted in a social revolution.

In an entirely unexpected way, this meeting led several Yugoslav musicians to transform themselves into skilled mariachis, singing the ranchera (in Serbo-Croatian) and dressed in charro suits and wearing sombreros.

BarBalkans will analyze the origin of this phenomenon - as forgotten as singular - with the support of writer and multidisciplinary researcher Fernando Martín Velazco, captain of Stultifera Navis Institutom, a creative expedition method-based research platform.

One of these expeditions was precisely focused on rediscovering the history and characteristics of Yu-Mex. In search of the unexpected mariachis in the utopian town of ‘Kamarones, Jugoslavija’.

Mexico. In Yugoslavia

To understand the reasons behind the rise of Yu-Mex and the huge Mexican influence in Yugoslavia, we have to go back to post-World War II. «Mexico had a big economic boost because the United States needed labor work and ideological influence», Velazco explains, talking about U.S. funding that led the Mexican film industry to grow with «a generation of extraordinary filmmakers and export of movies».

At the same time in Yugoslavia, with the breakup between Tito and Stalin in 1948, «there were no longer conditions for importing Soviet cinema, but neither was U.S. cinema». Therefore, only very few markets available remained in terms of production, other than Europe.

Read also: S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

But on the other side of the Atlantic, there was a country that had been producing good cinema with recognizable music for years, and that had experienced a revolution in the 1910s. «Even if it was not a socialist revolution like the Yugoslav one, and what emerged was a capitalist state, many elements of the Mexican revolutionary discourse were social», the creator of ‘Kamarones, Jugoslavija’ project points out.

All this made possible in 1952 the landing of the first Mexican film in Yugoslavia, Un día de vida by Emilio ‘El Indio’ Fernández. Velazco recalls that «while it was not successful at all in Mexico, in Yugoslavia was a total hit», to the point that Jedan dan života (in Serbo-Croatian) «became the most screened movie».

The plot of Un día de vida/Jedan dan života reveals the very reason for the Mexican music boom in Yugoslavia. Two brothers - generals during the Mexican Revolution - find themselves divided at the end of the civil war: one is sentenced to death for high treason and the other must capture him for execution.

The last wish of the man sentenced to death is one more day of life to visit their mother on her birthday, and sing together Las mañanitas, «a song that everyone knows in Mexico».

The success of the film in Yugoslav theaters was probably connected to some recognizable themes: social revolution, civil war, betrayal, family relations. Since that moment, «some musicians started playing this song, writing new lyrics in Serbo-Croatian», Velazco reveals.

In other words, new versions with the same melody - but with different lyrics and different intentions - appeared in Yugoslavia. «While in Mexico this is a happy song, in the former Yugoslav countries it became a sad song, dedicated to mothers who lost their children».

Las mañanitas - or Mama Huanita as it is also known - «became a very successful and popular song», which paved the way for more Mexican cinema and music in Yugoslavia.

Under this influence, local musicians began to use Mexican melodies to write their own lyrics. And sombreros spread throughout the whole region, as Velazco points out: «Yu-Mex became a musical genre by its own».

Read also: S4E8. You should know who is Valter

An idealized image of unity

Yu-Mex became such a structured musical phenomenon that «in a film by Emir Kusturica it is said that this is “a safe thing to listen to”», Velazco continues. As it always happens in history, «music reflected what was happening in Yugoslavia» in the Fifties and early Sixties.

«If you listened to folk music you could be suspected of nationalism, if you listened to Western or Soviet music it could be dangerous as well». This is why «Mexican music was something totally safe».

Yugoslav musicians «made very good adaptations, making Yu-Mex a good movement», even if it was limited to the space of a decade. Afterwards, Yugoslavia formed its own more structured music and film industry.

Read also: XXVII. New Year’s Eve with Tito

There is no doubt that the founder of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Josip ‘Tito’ Broz, fostered the rise of Mexican culture in the region. «He was a fan of Mexican music and mariachis», Velazco reveals, citing 1956 New Year’s Eve pictures in Luxor, Egypt, while wearing a sombrero. Tito was also close friends with Mexican President Luis Echeverría, who «gave him the gun of Emiliano Zapata, one of the Mexican Revolution leaders», according to urban myths.

But this is not the only issue that fascinates those who study the Yu-Mex phenomenon.

«The image of Mexico reflected in these movies is a complete invention», explains Velazco: «Only few elements from some specific regions of Mexico were taken». Mariachi iconography has become a national symbol, despite the fact that «it was only for a small part from Mexico».

The Mexican government’s effort to create an image of unity for a country emerging from a civil war was especially successful in Yugoslavia, because «the image of Mexico was fictional, but it worked very well for that audience».

In short, when Yugoslav musicians used those melodies and themes - even singing ¡Que viva México! - «they were talking about a Mexico that did not really exist and that they could not know».

After World War II, an image of unity and social revolution inevitably had a great attractiveness in Yugoslavia. A newly formed, non-aligned country that «needed a new narrative and had to deal with different identities».

In search of Kamarones

Lost in the folds of history - in the decades that saw the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the transformation of Mexico into one of the main powers of Latin America - Yu-Mex recently re-emerged also thanks to a cultural project by Stultifera Navis Institutom.

«The research expedition was carried out in the summer of 2018 in Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was an adventure to the former Yugoslav countries to find out more about mariachis in this region», Velazco tells BarBalkans.

‘Kamarones, Jugoslavija’ looked for to a utopian Mexican country in the middle of the Balkans, a fictional narrative used to trigger a collective memory.

The name ‘Kamarones’ is not related to Yugoslav history, but to Mexican history: «In the mid-19th century, France invaded Mexico and put an Austrian emperor [Maximilian I, ed] on the throne». Near the village of Camarón, the Mexican Army and the French Foreign Legion fought a great battle: «The invaders were defeated, but they fought with such great valor that the Mexican generals let the survivors live».

The hymn of the French Foreign Legion refers to the battle that took place in Camarón - “Héros de Camerone et frères modèles, dormez en paix dans vos tombeaux”. However, the creator of ‘Kamarones, Jugoslavija’ project was even more surprised to hear this story from a man in a kafana in Belgrade: «I thought it could be a nice name for a utopian town in former Yugoslavia».

During the expedition in search of Kamarones, Velazco found that «there is some kind of emotional connection» with Yu-Mex, «more intimate than socio-historical». Although not necessarily related to the history of Yugoslavia, «some people remembered Mexican music as a strange taste related to their grandparents». This is why «I think it was a powerful topic to bring back family stories».

Beyond the documentary research, «an interesting aspect of this project was ‘performing Mexicanity’ in public spaces of former Yugoslav territories». People took part in a Mexican performing game, which included singing an old song together (in Spanish and Serbo-Croatian) and wearing a sombrero: «The reaction used to be very kind, enthusiastic, and even theatrical».

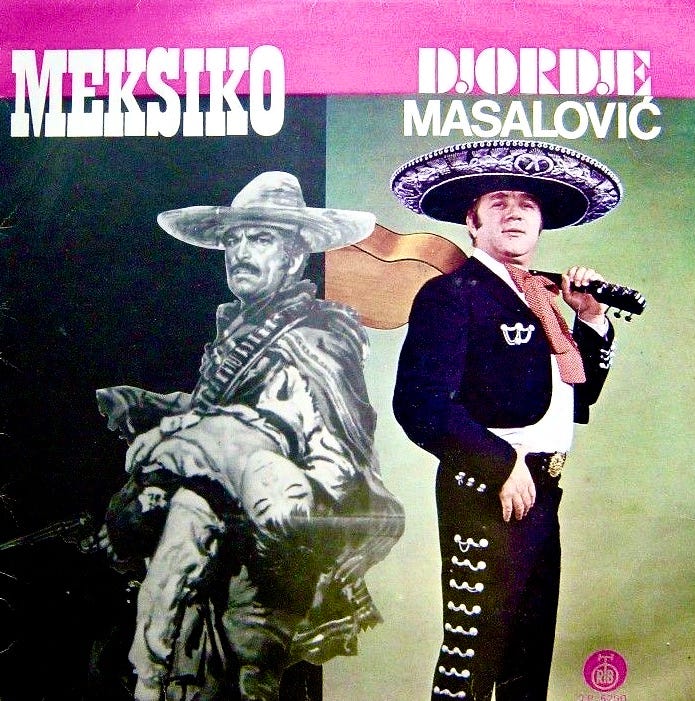

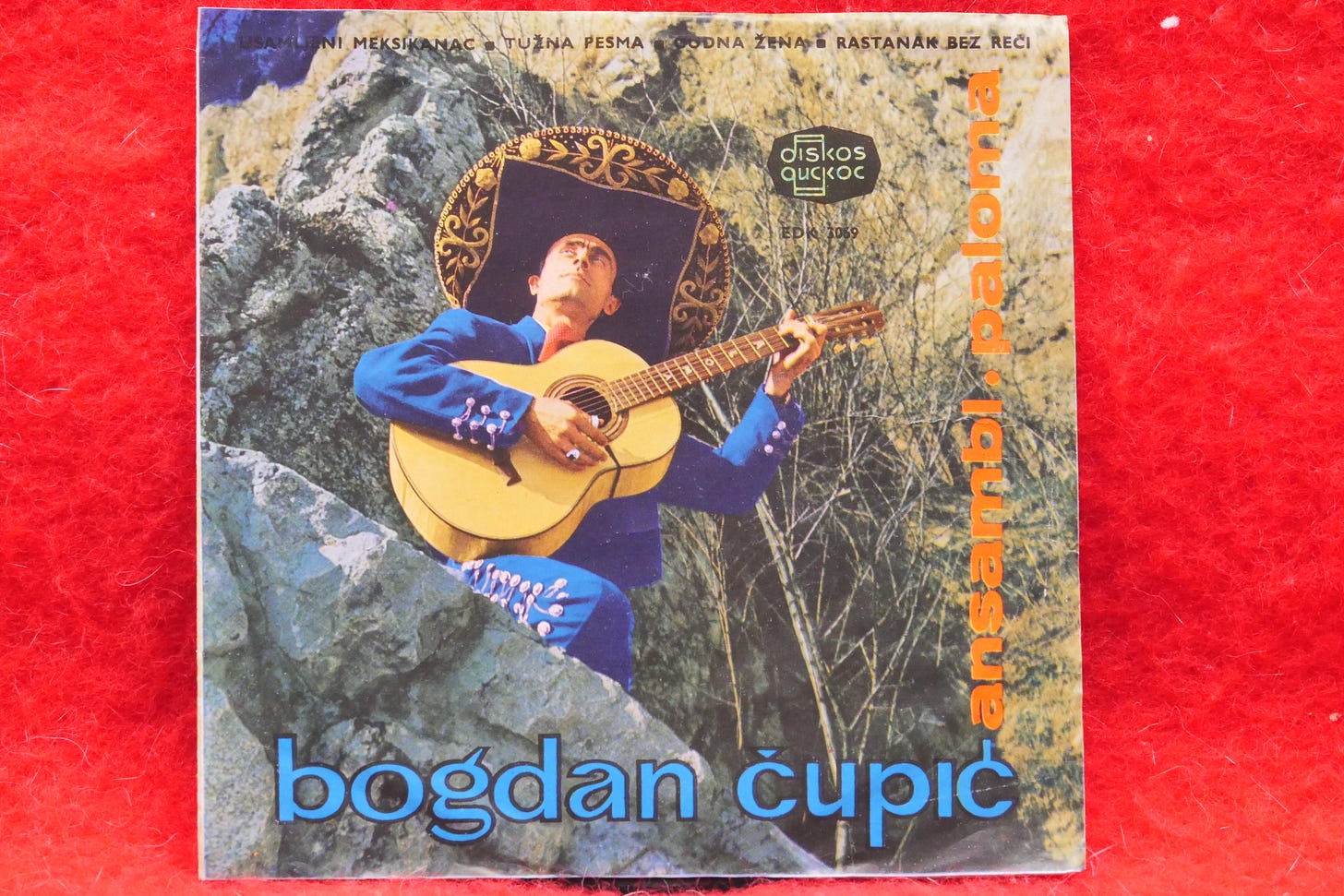

As it was the case with Yugoslav musicians and singers, who pretended to be mariachis more than a half a century ago. «The Yu-Mex LPs used some prototypical Mexican iconography or photographs of Yugoslav singers dressed as Mexicans», which is definitely unexpected for today’s Mexican audience. «It is very strange to see a Mexican wearing a mariachi suit in everyday life, even more so on Yugoslav people from the Fifties», Velazco confesses.

For all these reasons, ‘Kamarones, Jugoslavija’ «was an interesting research on both regions, their identities, their false sense of unity and their music». Once, it was the Balkans that played and sang Mexican music, but «ironically, today Balkan music is starting to become very popular in Mexico!»

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of the road.

Guided by our host, who followed the path of Mexican culture in what was once Tito’s Yugoslavia, today our bar, the BarBalkans, inevitably stops in the utopian Balkan-Mexican town of Kamarones.

«I wonder what a margarita made with slatko [a thin fruit preserve made of plum, ed] or žižula [jujube, ed] would taste like», Velazco smiles.

«But I think for the Yu-Mex spirit, shots of rakija and tequila, listening to mariachi music, would work». As the creator of the ‘Kamarones, Jugoslavija’ project confesses, «the most amazing stories related to this research emerged from sharing these drinks with different people from the former Yugoslav countries».

Read also: S4E13. Gastronationalism tastes like nothing

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 18th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

If you have a proposal for a Balkan-themed article, interview or report, please send it to redazione@barbalcani.eu. External original contributions will be published in the Open Barsection.

The support of readers who every day gives strength to this project - reading and sharing our articles - is also essential to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone.

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support BarBalkans will be able to elaborate new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans - right in that month - 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of The Yugoslav Wars every month on Spreaker and Spotify.

If you no longer want to receive all BarBalkans newsletters (the biweekly one in English and Italian, Open Bar external contributions, the monthly podcast The Yugoslav Wars for subscribers), you can manage your preferences through Account settings.

There is no need to unsubscribe from all the newsletters, if you think you are receiving too many emails from BarBalkans. Just select the products you prefer!