S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

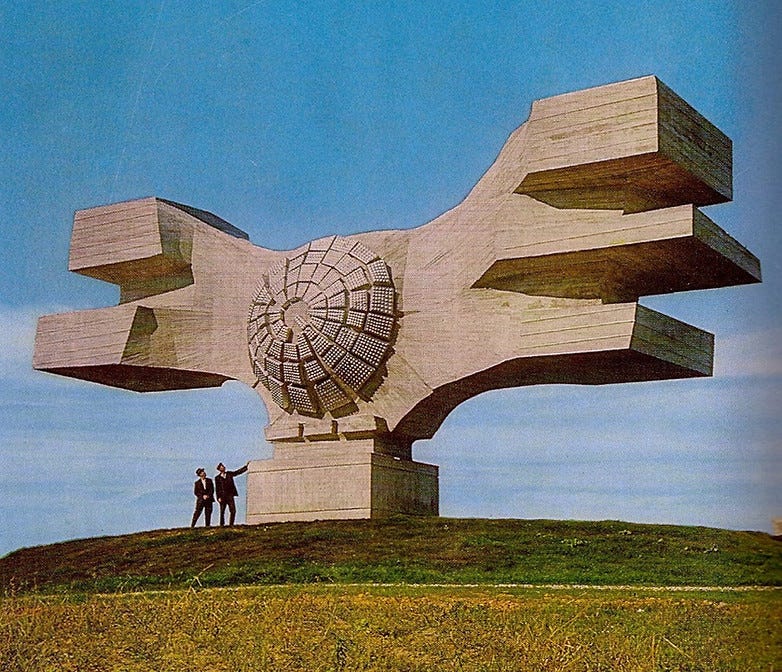

These concrete blocks are more than monuments: they are spread throughout the former Yugoslavia and recall Tito's Federation utopian ideals. Recently, Donald Niebyl has inaugurated a mapping project

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter (and website) with blurred boundaries.

There are words that are much more than mere words.

Some words can contain an entire universe of concepts, so much that it seems disrespectful for their complexity to translate them into another language.

Also among the Slavic languages in the Western Balkans there are several of these words.

Of course, we can always find a term or a periphrasis to describe them. But would it not be more accurate to dig into the meaning of these words and discover stories we have never imagined?

Today, we will discover one of these peculiar words, together with a guest who has turned an almost untranslatable concept into a disruptive socio-cultural project.

We set off to discover former-Yugoslavia’s spomeniks with Donald Niebyl, founder and curator of the Spomenik Database project.

Much more than a monument

Spomenik is the Serbo-Croatian/Slovenian word that can be translated with monument.

But with the word spomenik we are referring to a series of memorials built from the Fifties to the Nineties in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to honor the resistance struggle against Axis occupation during the Second World War.

They do not only commemorate the victims of the crimes during the occupation, but they also celebrate the socialist revolution lead by Marshal Tito’s Partisan Army through the People’s Liberation Struggle (1941-1945).

By 1961, over 14 thousands monuments were already built across Yugoslavia. And 30 years later, on the eve of the Yugoslav Wars, it is likely that their total number was up to 40 thousand.

In the first years of Tito’s Yugoslavia, there was the urge for a mass landscape-wide memorialization of the events of the People’s Liberation Struggle. Particularly, the aim was to give shape to a new Republic, ruled by principles of socialism, “brotherhood and unity”. The ‘Spomenik project’ was part of that great plan and it was a political tool meant to articulate the vision of a new tomorrow.

During the initial decade after the war, spomeniks were crafted in the figurative style of socialist-realism borrowed from the Soviet Union (USSR). However, while Tito opposed Stalin’s efforts to make Yugoslavia a Soviet satellite-State, also the creation of Yugoslav war memorials weakened its connections with socialist-realism.

As a consequence, anti-fascist war sculptural memorials began to spring up across the Federation in plastic styles - such as abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction, minimalism and brutalism - inspired by Western artistic movements.

These styles fitted well the Yugoslav need to redefine the sacredness of memorials, designed for an egalitarian society, free from the bonds of ethnic-nationalism, religious sectarianism and class conflict.

Instead of monuments built through historical artistic styles speaking of the past, geometric figures looking towards the future.

Before 1960, the construction of the vast majority of memorial spaces was largely un-directed and spontaneous. A few selected major projects in the immediate post-war period were directed by the government planning project, but 80% of spomeniks was represented by modest plaques, stone markers and basic memorial tombs initiated by local village leaders or small veterans groups.

After 1960, the State-run veterans group SUBNOR (Federation of the Association of Veterans of the National Liberation War of Yugoslavia) assumed all responsibility in directing and coordinating Yugoslavia's creation of monumental structures. The aim was to set up a less-chaotic system for the creation of monumental works.

When a memorial project was announced by SUBNOR, a monument planning commission took the lead of the spomenik creation. First of all, the commission launched a design competition. Any artist and architect could freely submit their own concepts and design proposals (open calls), or the planning commission choosed designs offered from a pre-selected group of candidates (closed calls).

When all design proposals were received, the monument planning commission selected a jury (made up of artists, architects, art critics, as well as politicians, party representatives, veterans and military leaders), who collectively and anonymously selected a winner.

As most of the personalities who composed the juries were part of the State institutions, the selected proposals closely reflected the desired political aesthetics. In any case, the anonymous design competition and the multidisciplinary juries guaranteed the selection of artistically ambitious projects, that might never have been otherwise considered for monumental applications.

Nowadays, a number of spomeniks are in state of disrepair, neglect, abandonment or complete destruction. This process began after the breakup of Yugoslavia and the independence of the former Socialist Republics.

Despite the efforts towards unity, many in Yugoslavia refused to fully integrate into the multi-cultural society, because of religious/ethnic claims, distrust towards communist leadership and anger about massacres during the Second World War.

As a consequence, in many areas where this anti-Yugoslav attitudes prevailed, the symbols of “brotherhood and unity” were the first target of destruction, as the war broke out in 1991.

In the new independent and ethnically conflicting States in the Nineties, spomeniks were often considered unwelcome reminders of an unwanted past. This was the reason for some militaries and political groups to erase them from the collective memory.

Since then, it is unknown exactly how many spomeniks survived. The misinformation on these memorial sites is not only due to a lack of cataloging, but also because they are still being actively neglected by local and regional governments.

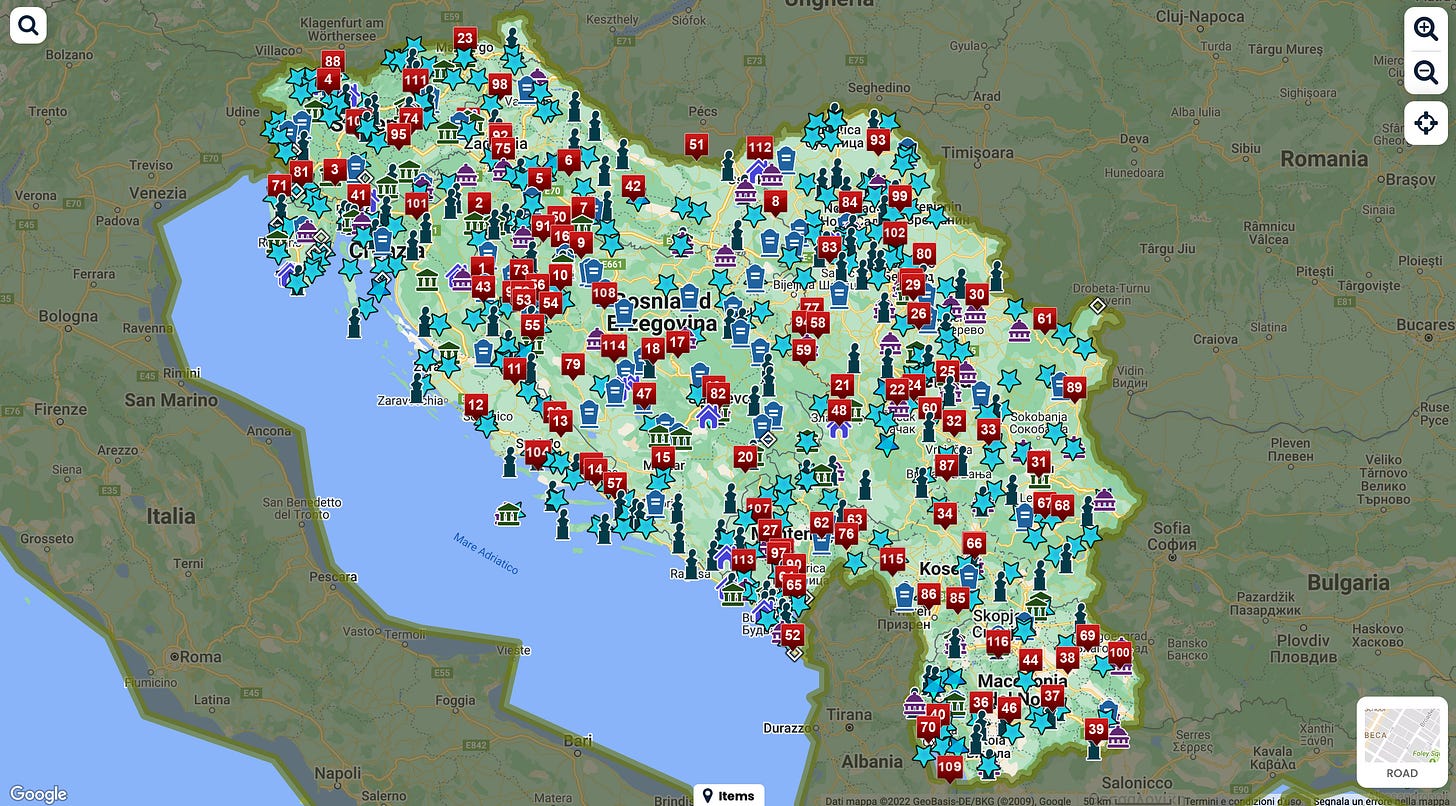

For all these reasons, in the last few years Donald Niebyl has been creating an online memorial site to compensate the almost non-existence of a comprehensive database with detailed information about the landscape of spomeniks.

Today, we have the chance to discuss directly with him.

A never-ending project

Donald, why did you decide to create a spomenik database?

«It all started back in 2015, when I first saw Belgian photographer Jan Kempanaers’ pictures. Those sculptural monumental forms spoke in grand universalist gestures but, at the same time, were lightyears beyond my naive American understanding.

In 2016, I spent about 3 months traveling across the Western Balkans, visiting as many of these monuments as I could. I captured hundreds of images, documenting their condition, pin-pointing their exact locations and directions.

I enlisted the help of locals to assist me in translating the monuments’ inscriptions, deciphering their history and understanding their cultural meaning.

Upon returning to the US, I created the Spomenik Database website, so that if anyone else wanted to find out information about these sites, it would have been easier to track them down and decipher their meanings.

There was an instant positive reaction from people around the world. With this encouragement, I continued to expand the website and upload more and more data.

Since 2017, I have been coming back to visit more sites every year, for at least one or two months. The project continues to expand, with information on the architecture, sculpture and history of Yugoslav monuments».

How many spomeniks are there now?

«It is hard to say in any exact numbers, but most certainly there are many thousands.

No one knows for sure how many, because there have never been any exact records kept on a national level. The destruction of many thousands of sites during the Yugoslav Wars has made it even more difficult to establish any exact number.

However, with the Spomenik Database and the research by Miran Hladnik in Slovenia and Andrew Lawler in Bosnia and Herzegovina, more work is being put towards systematically describing and cataloging these important heritage sites.

More than 6,400 Partisan memorial sites and objects in Slovenia have been documented by Hladnik. This is an indication on how many monumets we could expect to find in the other former Socialist Republics».

How difficult is to map spomeniks?

«When I first got started, finding geographic information on the specific locations was very difficult, as very little easily accessible data was available.

My early attempts consisted of scanning through aerial photographs where I suspected that monuments might be located. Even years later, I am still attempting to locate numerous sites.

Once I pin-pointed the sites on maps, the next step was finding them on the ground, which was not always so easy».

Can users contribute with reports and info?

«While my travels across the region are certainly one of the most significant sources for adding new details to the map, users and followers of my project are also a huge source of new information.

Just about every other day I have my followers reaching out to me, with pictures they have taken of previously undocumented monument sites. I really cannot stress the extent to which followers have helped me to expand the Spomenik Database.

The mapping is something that I am continually working on. I update the Spomenik Database map almost weekly with new info and additional interactive content».

Concrete barometers

What do spomeniks mean today for former-Yugoslavia countries?

«Each of the former Socialist Republics has a different relationship with the sites, and within every Republic as well.

These relationships can vary on the basis of culture, politics, religion, ethnicity, recent history. In one village you may find their Yugoslav-era monument in a pristine preserved condition, while the one in the next village completely destroyed or expunged.

In an overall sense, most of destroyed or neglected monuments can be found across certain regions of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. These monuments can operate as barometers in gauging the relationship that any given community has with its Yugoslav/Second World War history and heritage».

How has the project been received in the region?

«The response that the Spomenik Database project has received has been tremendous. Sometimes I receive messages even from the authors of the monuments or their descendants, sharing documents and information.

Furthermore, this website is one of the few places on the Internet where a select few of these authors are written about in English (or any other languages).

A small minority of the feedback that I receive are negative reactions, especially because I am a foreigner who writes about Yugoslav history. But I do my very best to make the writings and research on Spomenik Database be as thorough, unbiased and accurate as I possibly can».

Has this project started a specific tourism?

«From the online reaction I have seen over the years, there has been a significant surge in the touristic interest in visiting the Yugoslav monument sites, both from foreign and domestic tourists.

A cursory glance at the social media platforms will reveal thousands of people photographing themselves at these sites, something that would have been barely visible about 5 or 6 years ago.

Global tour outfits, such as Atlas Obscura or Soviet Tours, have been offering chartered and guided experiences to visit spomenik sites.

Meanwhile, in recent years I worked on a UN-funded project to develop a touristic cultural route centered around these Yugoslav-era monument sites.

While the momentum of that project was dashed by the COVID-19 crisis, I am confident that such efforts will most certainly come to fruition in the future».

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

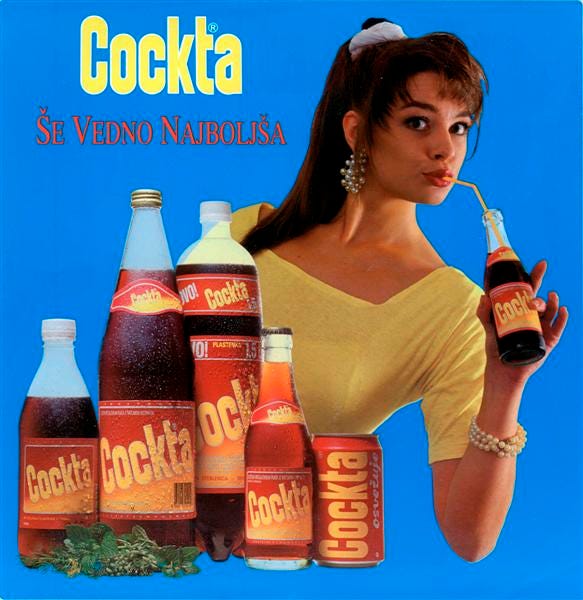

Today, we sit with our guest at our bar, the BarBalkans, and we discover a sort of spomenik for Yugoslav drinks.

Cockta was invented in 1952 in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia as a soft drink which would be able to compete with foreign brands and to compensate their absence in Yugoslavia (because of a governmental ban).

The Director of the State-owned corporation Slovenijavino, Ivan Deu, came up with the idea of producing an original beverage and the chemical engineer, Emerik Zelinka, an employee of the Slovenijavino research labs, created it.

The name comes from the word ‘cocktail’ and the new product was first presented on March 8, 1953, in Planica, at a ski jumping competition. That year, 4.5 million bottles were filled with a million liters of Cockta.

Cockta is still made of a blend of eleven different herbs and spices, including rose hip, the prominent flavor within the drink.

Let’s continue the BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 10th stop.

A big hug and have a good journey!

BarBalkans is a free newsletter. Behind these contents there is a lot of work undertaken.

If you want to help this project to improve, I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating. As a gift, every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans - right in that month - 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of BarBalkans - Podcast on Spreaker and Spotify.

Pay attention! The first time you will receive the newsletter, it may go to spam, or to “Promotions Tab”, if you use Gmail. Just move it to “Inbox” and, on the top of the e-mail, flag the specific option to receive the next ones there.