XXVII. New Year's Eve with Tito

Parties, sombreros, Maraschino and liver dumplings. The Museum of Yugoslavia (Belgrade) opens its archives to show how the founder of the Federation used to spend the last night of the year

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the Italian newsletter whose aim is to give a voice to the Western Balkans’ stories, on the 30th anniversary eve of the Yugoslav Wars.

This is the last stop of the year. Starting from the next one, we’ll live a “new” experience, on the anniversary of the Federation’s collapse.

Since we’re going to bid farewell to this first stretch of road and prepare for the new year, why not do it with the man who founded the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia?

So let’s get dressed up, wear the strangest hat we have and buy a bottle to toast the New Year with Tito!

[Thanks to Ana Panić, curator at the Museum of Yugoslavia in Belgrade, for opening the historical archive for us. All the photo credits go to the Museum of Yugoslavia].

A new idea of celebrating

In Yugoslavia the celebrations for the New Year gained special importance only after the Second World War.

Since 1919, Little Christmas - as the New Year was known in the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes - was seldom celebrated and only as a symbol of Europeanization.

But in the aftermath of World War II (1945-1947) the first advertisements for celebrations in hotels and restaurants appeared in the press. The USSR model was introduced in public places (city squares, army clubs, factories and workplaces).

Old and new holidays were mixed in an interweaving of tradition and new ideology. Christmas was still officially celebrated: the newspapers published a three-day holiday special with Christmas songs and greetings.

However, from 1947 there wasn’t even a hint of the Christmas atmosphere in the press. The old calendar of holidays, with its pre-revolutionary and religious connotations, had to be recoded.

A new socialist holiday was required.

In the post-revolutionary process of a comprehensive transformation of the society, the strategy of inventing traditions (State holidays, festivals and rituals) played an important role, as a means of preserving the social order and imposing new principles.

At the end of 1948, the least-politicized mass organization Women’s Anti-Fascist Front was put in charge of promoting the New Year’s celebration as the “future national tradition”, a children’s holiday, a day of joy for all workers who could sum up the results of the year.

Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) was criticized for being a creation of the Bolsheviks (after the Tito-Stalin split) and clerics, too similar to St. Nicholas. Instead, the central figures were a girl in national costume - as the personification of the New Year bringing in the future - and an old Partisan, in continuity with the revolution.

The trees were decorated with socialist symbols.

The authorities ordered to withdraw sweets and toys from the shops and then put them back on sale again immediately before New Year’s Eve, in order not to be on the market at the time of religious celebrations.

Through a combination of propaganda and coercion, the newly-created national holiday took its full shape at the end of 1949, replacing the former commemoration of religious festivals in the public life.

A little party never killed nobody

New Year’s Eve was proclaimed a state holiday in 1955, with the first general law on state holidays. It was meant to erase the borders between personal and social life.

Public celebrations’ primary function was to create a sense of belonging to the same community for all the people in Yugoslavia, regardless of their religion or nationality.

This was the general idea when the president of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Josip “Tito” Broz, visited public celebrations, got rides on trams and walked along packed streets to let ordinary citizens share their wishes for New Year.

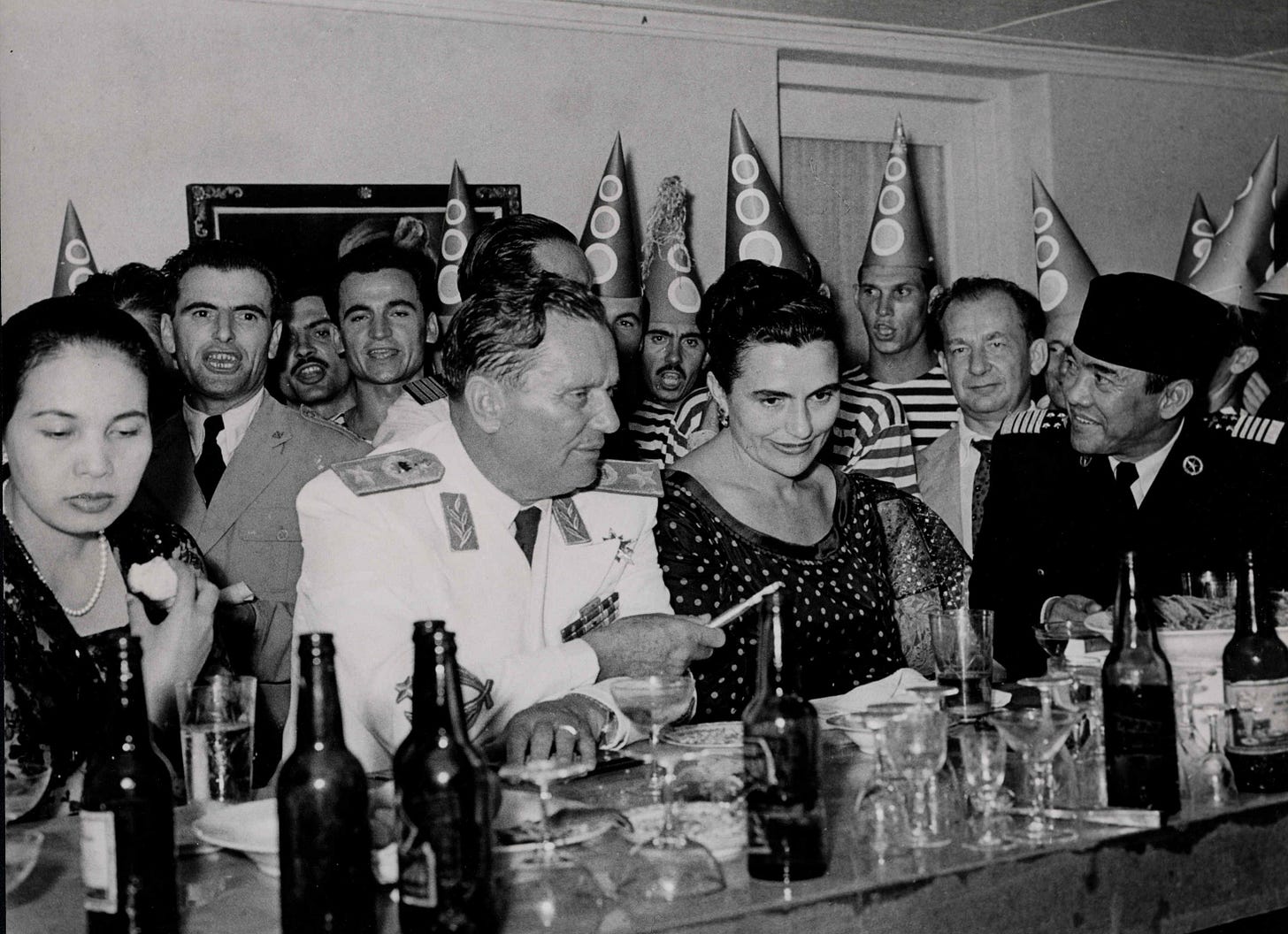

Moreover, Tito organized famous New Year’s Eve parties, where his partner was his wife Jovanka. His closest political allies joined them, while his numerous family members participated only a few years before Tito’s death (1980).

Parties were regularly held in the presidential residence in Belgrade, or in the other Yugoslav big cities. But Tito’s favorite place was his semi-private island, Veliki Brijun (the largest of a group of 14 small islands in the northern Adriatic Sea), where he spent 7 New Year’s Eve celebrations.

The most popular Yugoslav stars were invited and anyone could understand who his favorites were, comparing how many times they were invited to entertain him.

Even if the presidential protocol department was in charge to plan the party, Tito had the final say.

One of the party traditions was a social game called “funny mail”: the actors read and commented the postcards handed out to girls during musical performances.

Another characteristic of these parties was the dress code. Not only Tito’s, but also other guests’ suits and dresses were embellished with imaginative accessories. Like caps, hats, Mexican sombreros… Once, the mayor of Sarajevo wore a cap shaped as a tram, as an homage to the public service granted to his town in just one year.

Some awkward episodes happened in the years. For example, the search for an appropriate venue for New Year’s Eve 1956 in Egypt was very complicated. Tito and his entourage were accommodated in an ancient hotel: but there was the danger that the room would have collapsed, if thirty people had moved around at the same time.

Cheers! Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

And now at our bar, the BarBalkans, we have the privilege to host some of Tito’s New Year dinner menus.

Documents from the Archives of Yugoslavia tell us about the protocol, the guest lists with seating and performances and the very detailed organization of these New Year parties.

In some cases, even the menu proposal. Such as the New Year’s Eve 1978 at the Hotel Neptune on Brijuni islands. The menu was made up of mostly local dishes and wines:

Appetizer: Brijuni Overture + rich consommé and sea fruits

Main course: Festive potpourri + New Year’s pig accompanied by salad

Dessert: My dream cake + local tangerines from Vanga

Another one was the New Year’s Eve 1977 at the Park Hotel in Novi Sad. The menu included:

Appetizer: Vojvodina snack (homemade smoked ham, Slovak kulen, Sombor cheese)

First course: Carrot soup with homemade noodles and liver dumplings + cooked perch in Dutch sauce

Main course: Turkey, pork and veal roast with flakes

Side dish: Cabbage, baked potatoes and mixed salad

Dessert: Bačka strudel + pumpkin, cherries, walnuts and apples

Dulcis in fundo, Tito and his guests drank Riesling Sremski Karlovci (white wine) and Burgundy black Kutjevo. As a digestif, Maraschino, Cointreau and Grand-Marnier!

Let’s continue the BarBalkans journey. We’ll meet again in a week, for the 28th stop.

A big hug, have a good journey… and a Happy New Year!

I thank you for getting this far with me, in this trip started six months ago. Here you can find all the English newsletters published in 2020.

I invite you to subscribe to BarBalkans with your e-mail address, to receive the newsletter automatically every 2021 Saturday morning:

Pay attention! The first time you will receive the newsletter, it may go to spam, or to “Promotions Tab”, if you use Gmail. Just move it to “Inbox” and, on the top of the e-mail, flag the specific option to receive the next ones there.

And then you can invite whoever you want to subscribe to the newsletter. Just use this button:

BarBalkans is on Facebook and Instagram, too! Follow it on the social media to keep you updated on the news of the day.

On the Linktree page you can find a graphically pleasing archive.