S4E8. You should know who is Valter

'Wer is Walter?' project sheds new light on the collective memory and the history of resistance to nazism and fascism in Europe during WWII. Starting with one of the most iconic partisans in Sarajevo

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter (and website) with blurred boundaries.

There are stories that must be remembered. There is a European collective memory that needs to be reconstructed.

The history of the resistance movements to nazism and fascism all over Europe during World War II is a piece of 20th century that risks getting lost, due to negligence or to the rise of nationalist rhetoric.

Those networks of partisans’ movements fighting to free themselves from dictatorial regimes also operated beyond national borders. They gave birth to cross-border experiences, that could create a shared historical memory at a European level.

This is why it is important to give space to projects that address this specific need. For example, one with a very particular name and great ambitions: ‘Wer ist Walter?’ (‘Who is Walter?’)

Today, BarBalkans hosts two guests who can tell us all about this project. Elma Hašimbegović, Director of the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Nicolas Moll, the overall project coordinator.

They will explain us who this Valter is (‘Valter’ in Bosnian, ‘Walter’ in the other languages), but most of all why this is so important for the present day.

More than a symbol

So, who is Valter?

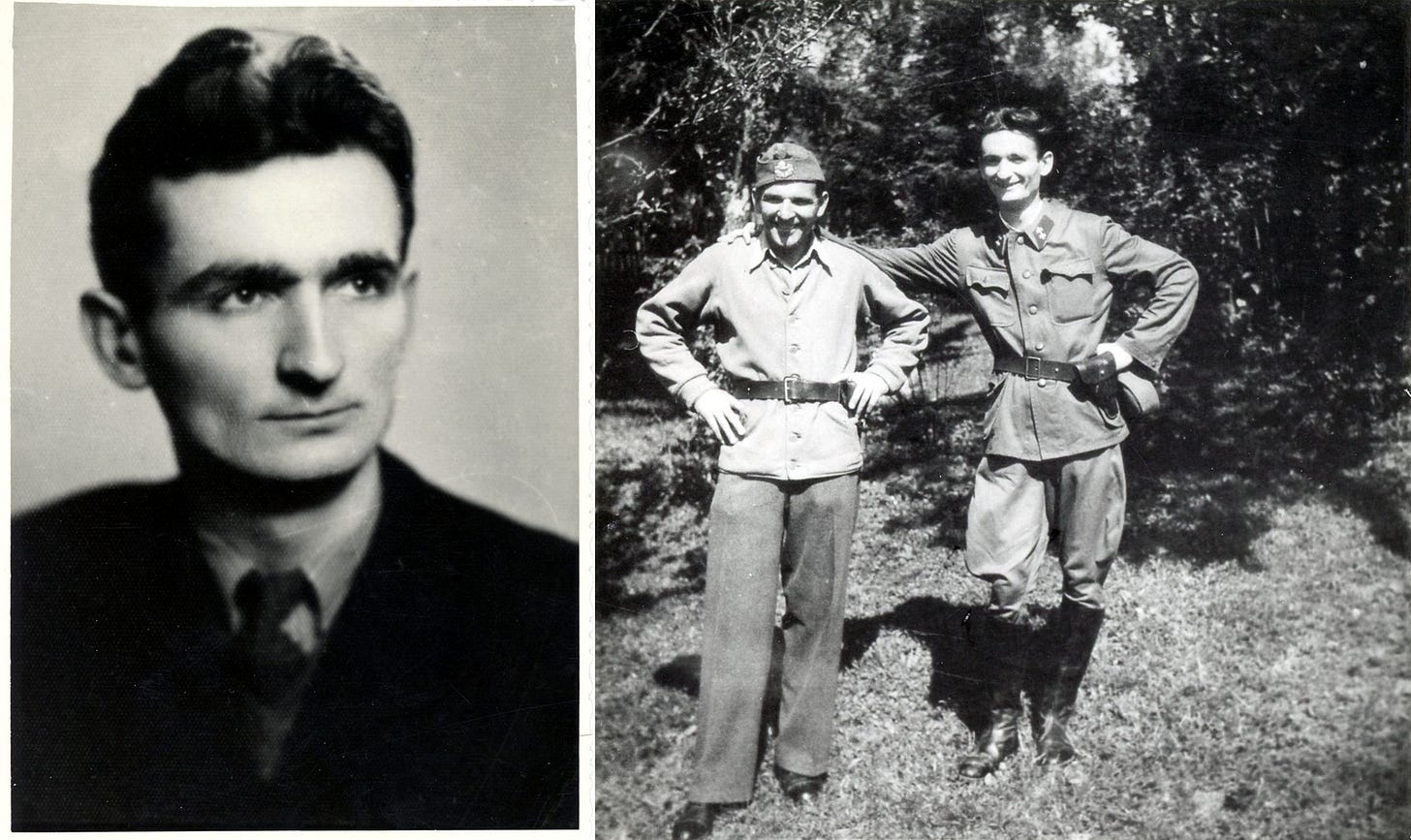

Moll: «‘Valter’ was Vladimir Perić’ nomme de guerre. He was one of the partisan leaders in Sarajevo during World War II. According to a report about the liberation of the city, “Sarajevo is liberated, but Valter is dead”. He was killed in the night of 5-6 April 1945, some hours before the partisan units entered Sarajevo».

And what did he represent during the resistance to nazism in Bosnia?

Hašimbegović: «Perić was appreciated all over the country during the war, but he was much better known thanks to his role of leader of the underground Resistance in occupied Sarajevo. He provided significant assistance to partisan units operating close to the city, he organized a network of partisan intelligence and was well respected by his fellow fighters inside and outside the city».

How was Valter portrayed in post-war Yugoslavia?

Hašimbegović: «He was better known after 1953, when he was awarded the posthumous ‘national hero’ medal for his achievements in the liberation war. However, his fame skyrocketed with the partisan movie Valter brani Sarajevo (Walter defends Sarajevo) in 1972. He became a sort of symbol of collective resistance in Sarajevo during World War II».

Read also: S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

And how does this story relate to your project?

Moll: «At the beginning, we were looking for a title for our project on the memory of resistance to nazism. We had very general ideas, not very attractive. Suddenly, we came up with the catch phrase “Wer ist Walter?” from the 1972 movie.

Due to his fake identity, German occupiers continue to ask themselves Wer ist Walter?, “Who is Walter?”. At the end of the movie, it is legendary the scene where a nazi officer says “Now I know where Walter is” and he shows another officer Sarajevo: “Do you see the city? This is Walter”.

We chose this phrase for different reasons. Firstly, the question mark is important to us. Nowadays, resistance to nazism is not one of the most popular topics in many European societies and we wanted to focus our attention on what we know about ‘the Walters’ everywhere.

Moreover, our project involves four countries – France, Germany, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina – and this reference also considers former Yugoslav countries. When we talk about European history and memory, we think about Western Europe, while Southeastern Europe is often a black hole. Through this title, we also aimed to reinforce the role of Yugoslav memory within a general European history».

How did the project ‘Wer ist Walter?’ originate?

Moll: «It all started in Sarajevo together with the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Museum of Revolution dedicated the partisan’s struggle. In the Nineties, when Yugoslavia fell apart, the history of World War II became less important and the role of this museum changed.

I remember when Director Hašimbegović told me: “We need to think about what we can do with all our cultural heritage, consisting on so many pictures, objects and documents collected during the 40 years of Socialist Yugoslavia”.

We asked ourselves what is the role of memory of resistance to nazism and fascism during World War II nowadays and what it can tell us. We started with post-Yugoslav countries, where this anti-fascist legacy can be challenging. But then, we realized that these questions are the same also in other European countries. The idea is to work on the history and memory in a European perspective and in some selected countries».

What is the timeline of this project?

Moll: «‘Wer ist Walter?’ is a two-year project, started in August 2022, with three outputs to be achieved: a scientific publication - for an academic audience - a digital platform with 100 stories of resistance in the four countries - for the general public – and finally an exhibition at the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Within the project teams of the four institutions, we gathered a group of experts composed of 12 people – historians, art historians, curators - who meet regularly to think about how we should arrive to these results.

During these two years, we scheduled four workshops and three conferences. The last conference will be in Sarajevo in July 2024. There, we will present the scientific publication, the digital platform and the exhibition. And there will be a reflection on how we can go on.

Even if it is a little bit arbitrary to focus only on these four countries, one of the most important aspects of our research is the transnational dimension of resistance: we are already considering the links between different countries, beyond the national perspective. For example, how partisans from Yugoslavia were involved in the liberation struggle in Northern Italy».

Fading memory

What is the knowledge about the partisan struggle in the four examined countries?

Moll: «In general, the knowledge is rather superficial or inexistent, uncritically glorified or uncritically demonized. It is often very selective, and this helps instrumentalization. This is why our project is not only about historical knowledge, but also a reflection on what is happening with this memory nowadays».

Hašimbegović: «In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the history of Resistance has been removed from the public space, as well as from school curricula, and this is one of the main reasons why new generations are not familiar or curious about the topic. The memory of World War II is ethnicized and often reinterpreted through nationalist perspectives. Furthermore, the memory of 1992-1995 war has become dominant».

Listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast: November ‘93. Falling down

How did the narrative of Resistance change with the dissolution of Yugoslavia?

Hašimbegović: «The whole dominating narrative of the multiethnic and antifascist struggle during Word War II totally changed with the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the Nineties. The newly born States did not need old heroes, brotherhood, unity and Museums of Revolution. The new nationalistic narratives did not support common history and legacy, so they erased them from the public space and memory.

Street and institution were no more named after partisans and historical figures from World War II, and even Valter ‘lost’ his school in Sarajevo. In any case, he was able to survive the change of narrative: we could say that “heroes are dead, but Valter survived”. In post-war Bosnian society Valter has become a symbol for anti-nationalism and against ethnic divisions».

As the memory of this historical period is increasingly fading away, what are the most effective ways to reintroduce knowledge among citizens?

Hašimbegović: «We are exploring different ways to raise interest and to bring new perspectives on this topic. Recently, we have worked on a project about the role of young people during World War II: how they reacted to war, their active or passive role, the choices they had. We used our historical material and we presented inspiring stories from the museum collections.

Being aware of the power of art, sometimes we also open our collections to artists, who can creatively relate to historical documents. Moreover, the outcomes of the project ‘Wer ist Walter?’ - the academic publication, the digital platform and the exhibition at our Museum - will certainly represent a great occasion to work with different groups of audience in the future».

A trans-European history

Why does the memory of the European resistance to nazism and fascism exclude what happened in former Yugoslav countries?

Moll: «I think we have to go back to the Cold War to answer this question. Between the Western and the Eastern blocks, Yugoslavia chose a third way of non-alignment after Tito clashed with Stalin. Somehow, Yugoslavia was outside the general interest of “Western Europe against Eastern Europe”.

With the unification of Germany, the fall of the Soviet Empire and the enlargement of the European Union, the Eastern countries’ narratives entered the European space, formerly dominated by Western countries. However, the exclusion of post-Yugoslav countries continued, because Yugoslavia fell apart in the Nineties and seven successor nation States took its place.

Slovenia and Croatia are part of the European Union, but they are more interested in the creation of a Slovenian and a Croatian memory, rather than promoting the major role played by Yugoslav partisans in World War II. The multinational dimension of Yugoslav space during socialist times - that was something apart in whole Europe - is not attractive for nationalist ideologies».

Read also: XXVII. New Year’s Eve with Tito

What is the risk related to a loss of this memory?

Moll: «The European memory of resistance against nazism and fascism is incomplete, if we continue to ignore the very important chapter of Yugoslav contribution to our common history. Yugoslav partisans succeeded in creating a real army and in freeing themselves from occupiers and collaborators, also thanks to the support of the Soviet Union, the US and the UK.

Moreover, we have to highlight the many links with other European countries. For example, the British government supported the Yugoslav Resistance. Thousands of Yugoslav partisans were deported to concentration camps in Germany. Yugoslav fighters - who took part in the Spanish Civil War and who moved to France after 1939 - became part of French Resistance».

Do you think it is possible to build a shared European memory, rather than just a national memory?

Hašimbegović: «Yes, we aim to share and broaden this knowledge among European historians and museum professionals thanks to ‘Wer ist Walter?’ project. But we also want to put the Yugoslav Resistance during World War II in its European context».

Moll: «I think it is possible to work on a European narrative, even though we can not pretend that a unified European resistance existed. In any case, there were partisan movements in almost all European countries, and it is important to point out the differences and similarities.

When we work on the European history and memory, it is important not to idealize the concept of resistance, because it had grey zones and problematic aspects: sometimes the border between Resistance and collaborators was fluid, and also partisans committed crimes. All these aspects must be considered, as we are trying to do with our project, giving inputs to progress with a European vision of Resistance to nazism and fascism».

Read also: S4E4. Jugeurope

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

Today our bar, the BarBalkans, travels back in time to find out what we could drink together with ‘Valter’ during the resistance against nazism in Yugoslavia.

Hašimbegović: «I am not familiar with any account of Vladimir ‘Valter’ Perić drinking slivovica. But I know for sure that his birth town, Prijepolje, is rich in plums and has a long tradition of making plum brandy. Therefore, I have no doubts that ‘Valter’ inherited this tradition from home!

Recently, I came across the episode in which Fitzroy MacClean, the Head of the British Mission to Yugoslav partisans in 1943, wrote about his first meeting with Tito at the headquarter in Jajce. The conversation was about British support to Tito’s partisans - as they were the only real force that made “Germans considerable inconvenience, especially in Bosnia” - as well as about future of the country at the end of the war.

The conversation was very fluid, because both of them spoke fluently German and Russian. But it became even smoother when they drank a couple of glasses of slivovica».

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 9th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

Your support is essential to realize all that you have read. And even more.

A job well done needs many hours and energy. Also to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone and to make it an increasingly original product, with new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

An independent project like this cannot survive without the support of the readers. For this reason I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating:

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans - right in that month - 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of BarBalkans - Podcast on Spreaker and Spotify.

Pay attention! The first time you will receive the newsletter, it may go to spam, or to “Promotions Tab”, if you use Gmail. Just move it to “Inbox” and, on the top of the e-mail, flag the specific option to receive the next ones there.