November 1993.

The pressure on the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina - inside and outside of Sarajevo - is overwhelming [you can listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast here].

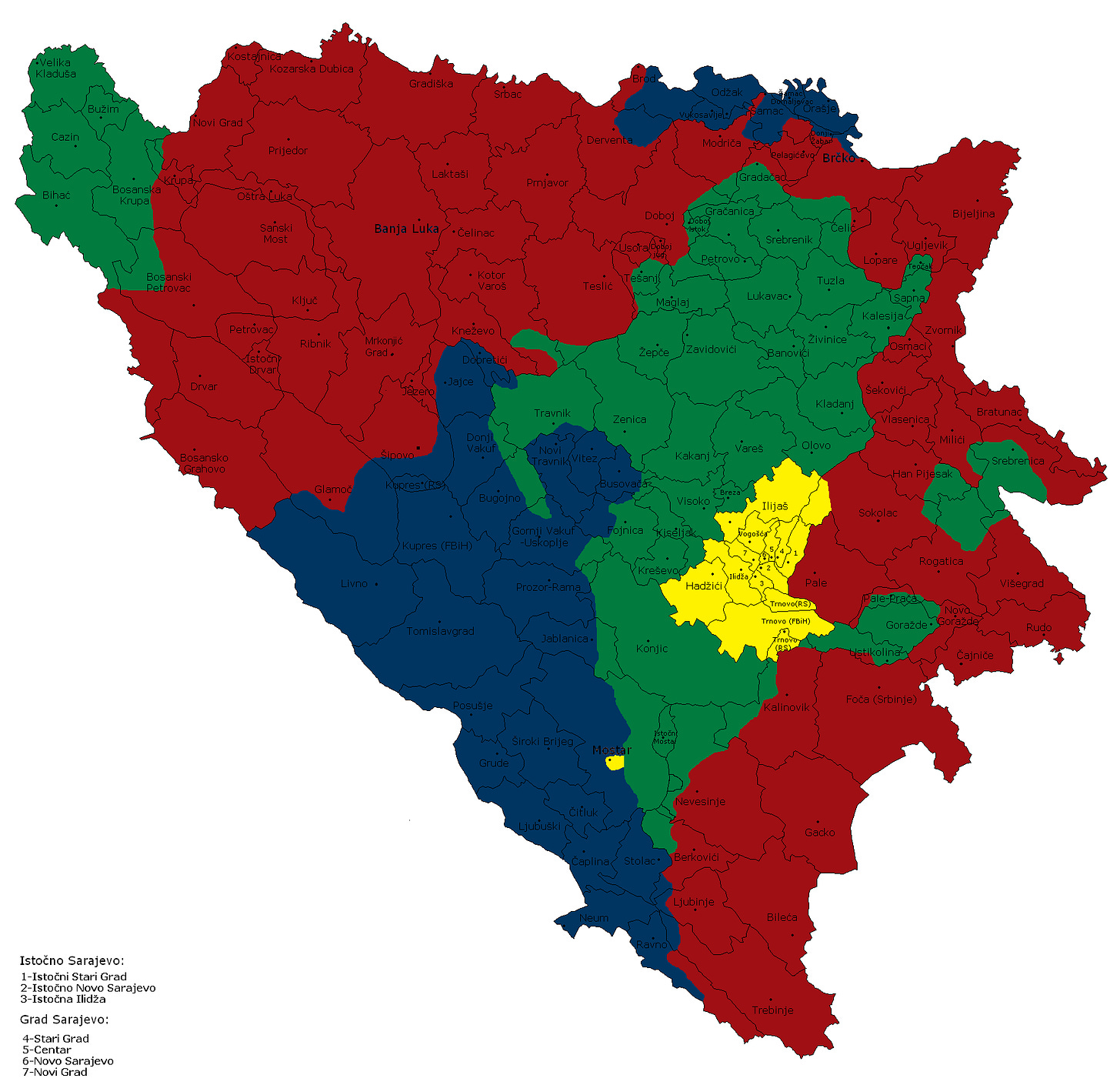

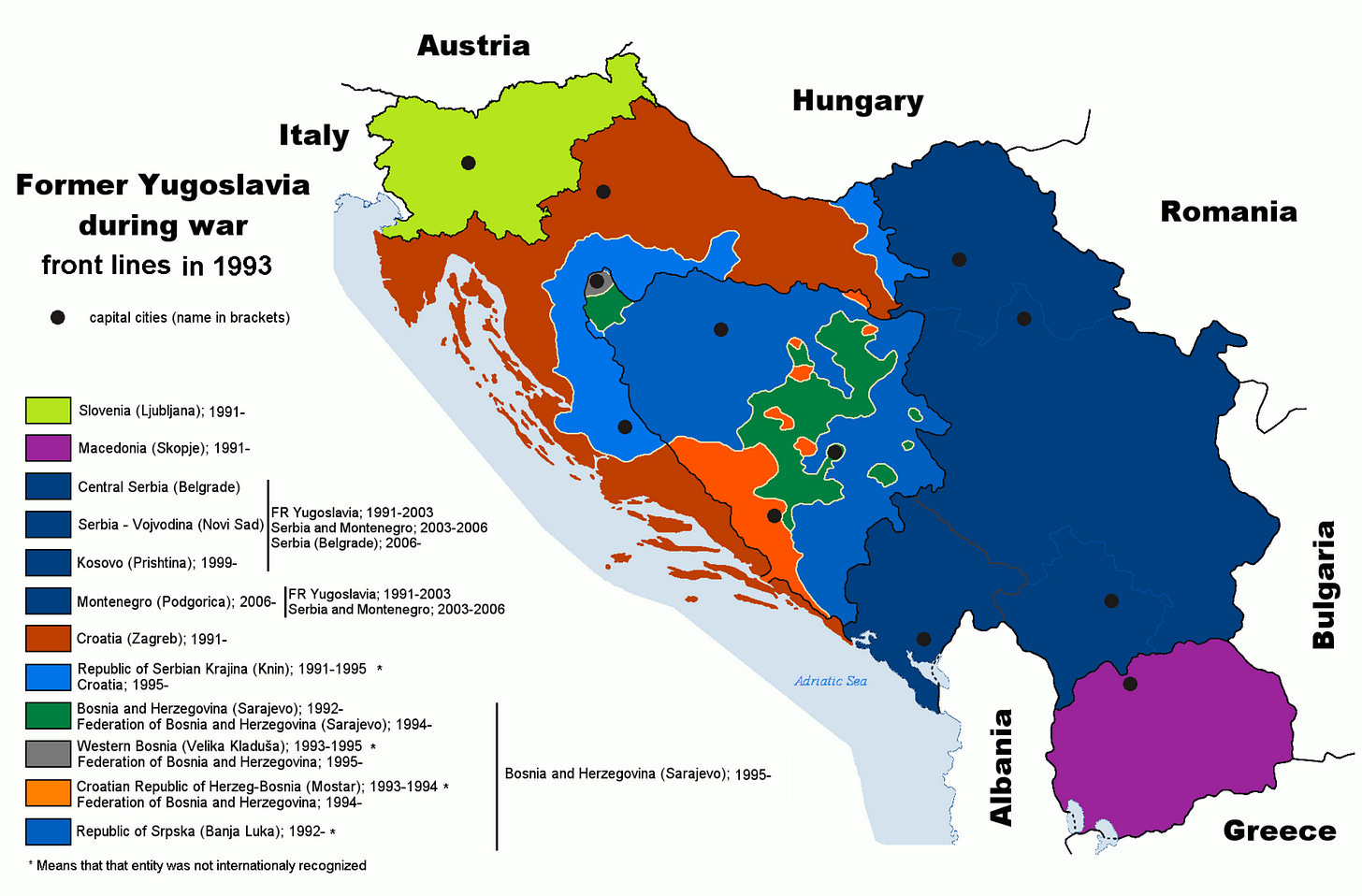

While Republika Srpska and the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia are imposing a blockade on the Bosnian capital, the situation on the battlefield is made more complicated by the new war front opened by the Autonomous Region of Western Bosnia.

However, the most heinous violence is taking place especially in the South. Together with one of the darkest episodes in Bosnian history.

Stari Most is falling down

Following the massacre in Stupni Do by the Croatian Defense Council (the Army of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia), the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina responds with additional violence on civilians on November 2.

The ancient mining town of Vareš is conquered and put to the sword, forcing more than 12 thousand people to flee from day to night.

The escalation of violence between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats continues to worsen, reaching its most tragic point from symbolic, historical, social and diplomatic perspectives.

The destruction of Stari Most.

The Old Bridge in Mostar was built in 1566 by order of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Considered one of the wonders of Ottoman architecture, it dominates the Neretva River with a single arch from a height of 24 meters and with two towers called mostari (“guardians of the bridge”).

The bridge is the symbol of the Herzegovina’s main city, as it connects not only the two banks of the river, but also two peoples, two religions, two ethnicities.

This is why the Croatian Defense Council considers the bridge as a military target. The unthinkable happens on November 9, shocking the whole world.

A Bosnian-Croat military unit destroys the bridge with several mortar shots from the heights above Mostar, while the soldiers celebrates the event.

Even if it was already damaged by Serb bombing in 1992, the Old Bridge was the last link between the Muslim quarter on the left bank and the Croatian quarter on the other side of the river.

Most of all, it represented the only access to drinking water on the right bank for some 55 thousand Bosniaks (even if they had to run from one side of the bridge to the other, avoiding snipers). From now on, these people are trapped.

Like the debris of the bridge at the bottom of the Neretva River, any hope of a multicultural Bosnia and Herzegovina disappears with the destruction of Stari Most.

The destruction of the Old Bridge in Mostar is a blow to Bosniak morale, but it does not affect the impressive developments following the conquest of Vareš.

Since November 2, the Bosnian Army has been able to connect the four regions of Sarajevo, Mostar, Tuzla and Zenica, with five army corps to resume the offensive in the most industrialized areas of the country.

An army of 80 thousand soldiers is now capable of confronting the Bosnian Serb and Bosnian Croat armies, thanks to the acquisition of substantial quantities of weapons received from allied Arab countries or purchased on the black market via Slovenia, Eastern European and former USSR States.

Even U.S. Stinger anti-tank missiles - obtained through intermediaries from Afghanistan - show up on the field. Together with advisers and specialized units from Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Jordan and Morocco.

The new European Union’s diplomacy

As of November 1, there is a new actor on the international scene. The European Union. Actually, it has just changed its name (from European Community) with the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty, signed on February 7, 1992.

The new European Union makes its debut only a week later with the first draft of a peace plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina, following the failure of the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan.

On October 8, the Foreign Ministers of Germany and France - Alain Juppé and Klaus Kinkel, respectively - send a letter to the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the European Union, detailing their proposal to solve the crisis in former Yugoslavia.

XXX In reality, the Juppé-Kinkel Plan does not differ a lot from the principles of the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan. With the exception of two factors: an additional 3.6% of territory to Bosniaks (from the original 30%) and the gradual - and explicit - lift of international sanctions against Yugoslavia.

Even this new plan is born crooked - as it is criticized from both the European public opinion and the U.S. administration - it succeeds in bringing the parties back to the same diplomatic table.

On November 29, a new round of peace negotiations of the Conference for the Former Yugoslavia opens in Geneva. It is chaired by the European Union’s negotiator for the former Yugoslavia, David Owen, and the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative, Thorvald Stoltenberg.

The meeting is attended by the leaders of Serbia, Croatia, the three Republics in Bosnia (the official one with capital Sarajevo and the self-proclaimed Republika Srpska and Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia), the 12 European Union Foreign Ministers, and U.S. and Russian delegates.

The atmosphere is tense and none of the parties to the conflict are willing to make concessions. Only the Serbian President, Slobodan Milošević, leaves the Conference significantly strengthened.

With his classic rhetoric that shows Serbia as a «victim of an international conspiracy», he can focus again on electoral campaigning ahead of the December 19 vote for the renewal of the Serbian Parliament.

A historical Tribunal

As diplomatic efforts continue with extreme difficulty, November 17 becomes one of the most decisive dates in Balkan contemporary history.

The inaugural session of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia takes place in The Hague, in the Netherlands.

The International Tribunal’s objective is to prosecute those responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide on the territory of former Yugoslavia since 1991. Its birth was sanctioned in February 1993 by UN Security Council Resolution 808, and its composition was later defined by Resolution 827 on May 25.

It consists of 11 judges divided into 3 chambers (two first instance and one appeal), a prosecutor and a court clerk. They are all elected by the UN General Assembly, except for the prosecutor by the Security Council.

All UN Member States have a duty to arrest and take to The Hague whoever is accused by the prosecutor of having «organized, instigated, ordered, or otherwise aided or abetted the organization, preparation or execution» of crimes within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.

The Tribunal aims high, but the gap between ambitions and the real possibilities of implementing the warrants raises enormous doubts. Even in its President, Italian Antonio Cassese.

Not least because some States - especially France and Britain - oppose some appointments that could be decisive for incisive action.

Starting with the appointment of Egyptian Cherif Bassouni as prosecutor. The fact that he is Muslim is not enough. The truth is that he has already conducted investigations in former Yugoslavia as head of the UN Security Council’s Commission of Experts in October 1992.

Where he gathered evidence about war crimes ordered by the same interlocutors who were promised the largest portions of Bosnia and Herzegovina by the EU negotiators.

With a prosecutor like Bassouni at its core, the Tribunal would be too dangerous for Western diplomacy.

If you know someone who can be interested in this newsletter, why not give them a gift subscription?

Here is the archive of BarBalkans - Podcast:

And here you can find a summary of the past years:

Share this post