S4E4. Yugeurope

In Brussels, at the heart of the EU, the House of European History showcases integration processes across the continent. Some initiatives highlight the role of extinguished countries like Yugoslavia

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter (and website) with blurred boundaries.

Balkans. Europe. Yugoslavia. European Union. Western Balkans.

A thousand newsletters could be written about the links, the misunderstandings, the plots, the disagreements and the efforts for convergence between one of the most complex European regions and the rest of the continent.

There is a whole world to be discovered - starting from the word ‘Balkans’ - that can reveal a lot about the way we conceive and describe this peninsula.

When it comes to analyze the relations between the Balkan region and the Western European countries on a historical level, it becomes much more evident how the present can be influenced by highlighting or glossing over the common past.

This is not just historiography for a few experts, but a question for anyone who asks themselves: where do my prejudices come from?

To be more conscious about all this, we can enter one particular museum in Brussels. In the heart of a European Union that is struggling to integrate the six Western Balkan countries into the project of peace, stability and democracy.

A House for the Europeans

The House of European History was conceived in 2007 as an idea of former President of the European Parliament Hans-Gert Pöttering. The exhibition space of about 4 thousand square meters was inaugurated on 6 May 2017.

Admission is free and over the years this museum has become one of the landmarks in Brussels for tourists from all over Europe, who want to learn more about the history of integrations across the continent. This is possible thanks to a permanent exhibition of objects and documents, temporary exhibitions and cultural events. All in the most technological way possible.

With a tablet and an audio guide, you can walk through five floors of exhibits, following the twists and turns of European history. And you can pass from one historical moment to the other, while discovering how events in one country had an impact on the rest of the continent.

And even if you sense that the museum is slightly leaning towards the Western countries’ history, it is true that you can have an almost full overview of the social, cultural and economic exchanges that have made Europe what we know today.

«The House of European History aims to tell a transnational history of the European continent, focusing on the 20th century and trying to answer questions relevant for today’s Europe», curator Simina Bădică tells BarBalkans, stressing that «even if we mainly display the 20th century, our exhibition is very dense».

Read also: S3E16. At the Heart of Empire

There is a recurrent question for contemporary Europe, from the beginning to the end of the permanent exhibition: what is the relationship between Europe and the European Union?

«I believe the confusion between Europe and European Union is one of the misconceptions that the House of European History skilfully and consistently challenges», the curator claims. Although in everyday life the two words are wrongly used as synonyms, «if you look closely at our exhibition texts, you will find that the two concepts are very clearly separated».

More precisely, the difference between the word ‘Europe’ and ‘European Union’ also concerns the relationship with those countries that are not in the EU project (yet). Such as the the so-called Western Balkans: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia.

«I think we have achieved a good balance at the House of European History, a balance in which Eastern Europe and the Balkan countries are very much present». Also considering the background of people who shaped the museum: «Our first academic project manager was a Slovene curator, Taja Vovk van Gaal», Bădică recalls.

There is more. «The balance that we aim to keep is not only between East and West, in itself quite a historical division», but also «between North and South, gender balance, personal stories vs. State narratives, and so on».

This is how that the permanent exhibition can be read through a thousand different lenses. Including the lens focused on the Balkan contribution to the construction of Europe.

Read also: XXXIII. Culture from your couch

A Balkan tour

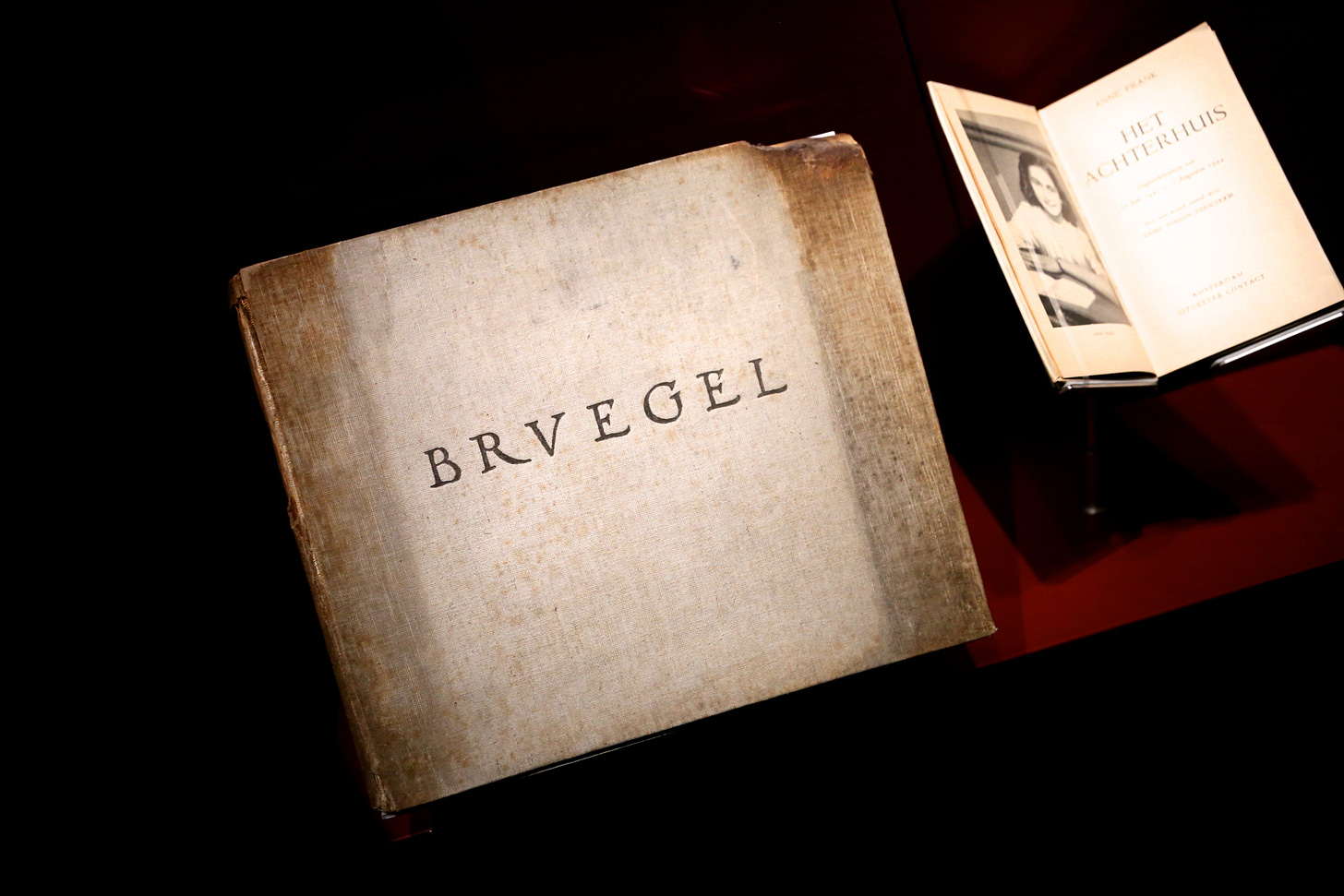

Our tour - which can also be followed virtually - starts with a book about Bruegel. This is one of the few books rescued from the National Library in Sarajevo and that did not turn into “black butterflies”, pieces of pages in ashes poured over the city after the bombing in 1992.

After some considerations on the common cultural heritage and on the division of the Balkan peoples into different Empires - Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman - between the 19th and 20th centuries, we enter a black room. In the center of the room, inside a display case, there is a pistol: the same model used by Gavrilo Princip in 1915 to kill Archduke Franz Ferdinand, setting off the series of events that led to World War I.

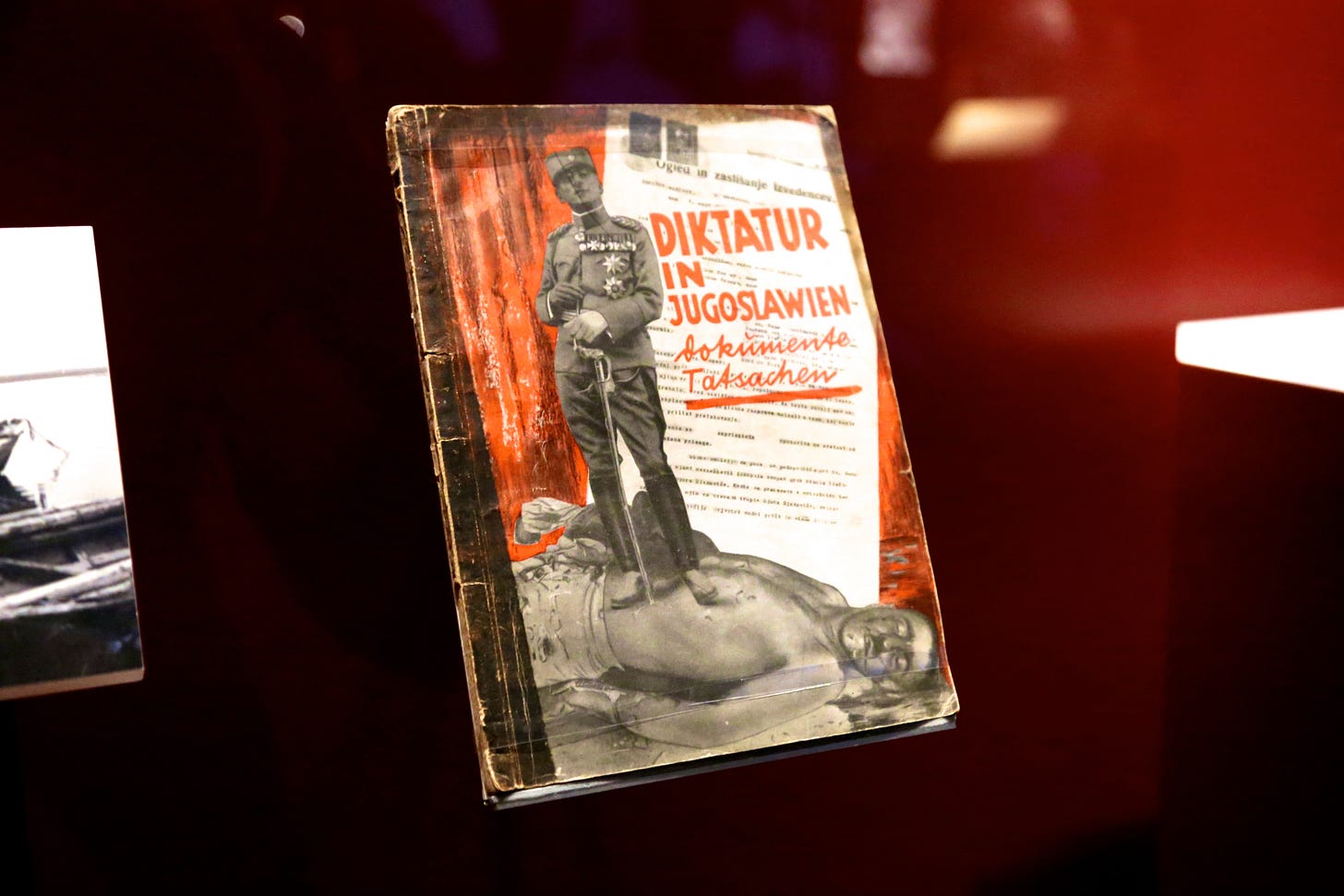

The term ‘Yugoslavia’ - “Land of the South Slavs” - first appears on exhibition’s maps with the birth of post-war kingdoms. This is a complex period, made of hard clashes and efforts to create a common identity, as illustrated by the pamphlet Dictatorship in Yugoslavia.

The region is occupied by nazi Germany during World War II, with different policies adopted according to the movements present on the ground. For example, nazis give birth to the Independent State of Croatia, a puppet State - that also includes present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina - led by the Ustaše.

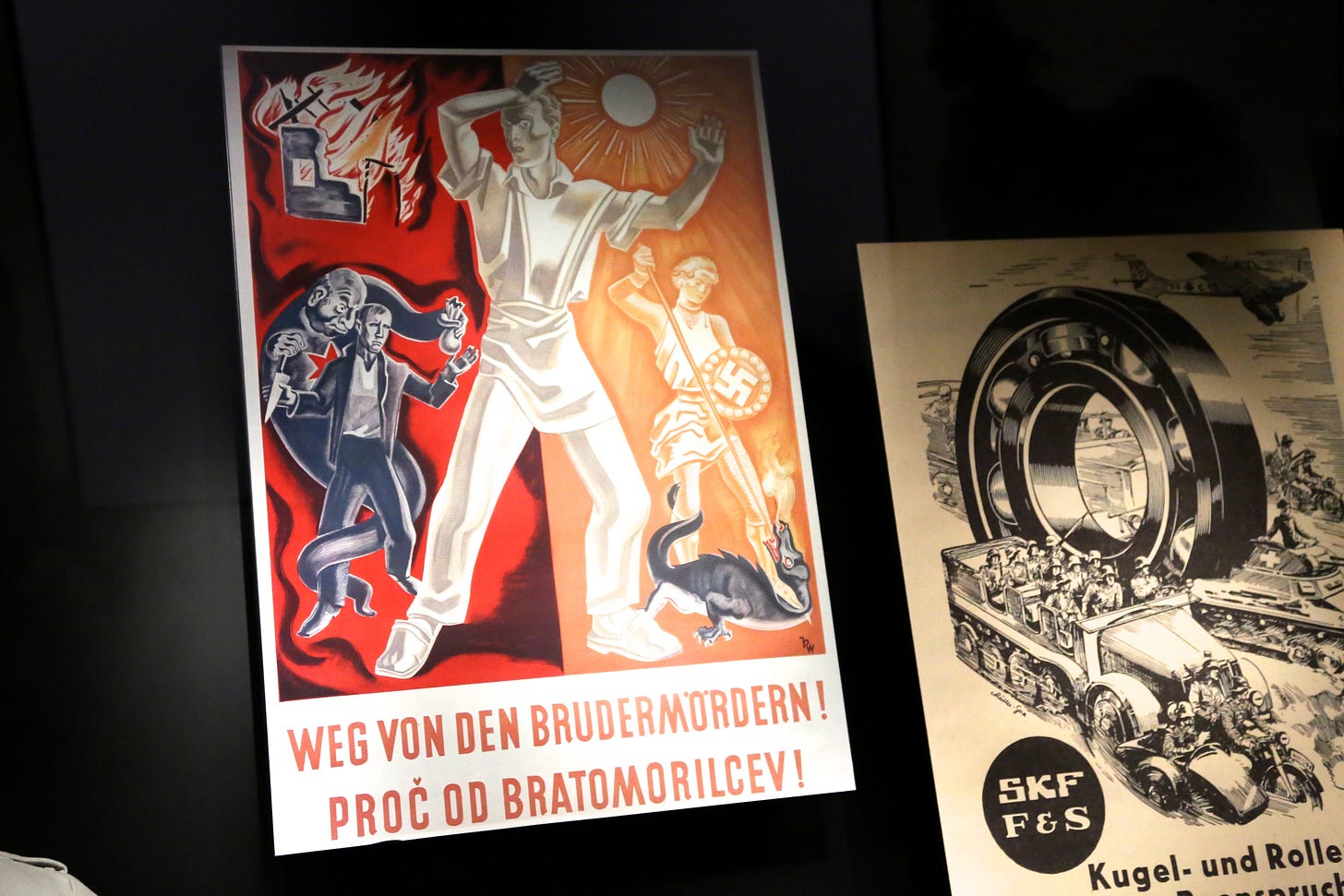

This is a typical fascist movement with enemies to persecute: Jews and Serbs. Some pictures show ethnic Serbs expelled from Bosnia, as well as Jasenovac concentration camp, where more than 100 thousand people died. And there is also a peculiar poster.

It is written in German and Croatian - Away from the fratricide - and represents a man in the middle of two scenes inspired by the Ustaše propaganda. On one side, a stereotyped Jewish devil with a red star on his chest, offering a knife and money. On the other side, a nazi angel slaying the dragon (symbol of the Bolshevik-Jewish conspiracy).

As in the rest of Europe, a partisan liberation struggle against the occupiers takes place in Yugoslavia. In regions like Serbia and Bosnia, this is also a struggle against the Ustaše administration. The framework is even more complex because of the Chetniks, the Serbian nationalist movement loyal to King Peter II of Yugoslavia in exile: they ally and fight against everyone, according to the specific situation.

Thanks to the partisans led by Josip ‘Tito’ Broz (whose winter war uniform can be seen in a display case), Yugoslavia is the only country to get rid of the nazi occupation and the collaborationist regime on its own.

Read also: XXVII. New Year’s Eve with Tito

However, all ethnic horrors of the recent past pass over in silence in the post-war period, while the rhetoric of liberation targets only nazis and fascists. In the name of a unity - which never existed - necessary for the construction of the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The Zastava 750 SP Luxe (the most famous car manufactured by Zavodi Crvena Zastava, under license from Italian Fiat) brings us in the Yugoslavian world of the Sixties and Seventies, surrounded by the economic boom throughout Europe. The car in the center of a large room is a physical representation of the desire to forget wartime and to improve living conditions.

But this vehicle is also a metaphor for Yugoslavia. Something that is not perfect, that often does not work, but can be fixed somehow through human relations. This is a time when intermarriages are very common and when Zastava 750 allows families to travel on holiday.

Everything changes with the fall of the Socialist Federation. As the maps show, the borders of the newly independent States change under the pressure of ethnic groups. People can no longer be ‘Yugoslav’, it is necessary to identify with (and belong to) a specific ethnic group, opposed to the other “enemies”.

Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Albanians, Macedonians, Slovenes, Montenegrins. Although an institutional memory about World War II has always been neglected, the massacres of the past have never been forgotten at the family level. And now they become the playground for propaganda and ethnic hatred.

Among all the Yugoslav Wars in the Nineties, the main focus is on Sarajevo, as it represents the longest siege in modern European history (from 1992 to 1996).

Videos of the siege, objects like a homemade rifle and United Nations materials reused by the civilian population for everyday needs (such as a gasoline can turned into a watering can) give a real dimension of the suffering of a European people in the middle of a heinous war only 30 years ago.

Listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast: September ‘93. The season of internal strife

Parallel paths

The tour we have just taken together with our minds is an actual itinerary created by the House of European History.

Every Tuesday, the museum’s learning team dedicates a ‘lunch tour’ to a specific topic, part of a monthly macro-theme. ‘Countries that have ceased to exist’ was September’s theme and ‘Yugoslavia’ was the third topic.

«This theme resonates with many parts of our permanent exhibition», Bădică - our guide for the Yugoslav tour - points out. «There was quite some demand for a thematic tour on the USSR or Yugoslavia, so we decided to group them under the same theme», along with the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires.

The tour, focused on the history of the Balkan countries in the 20th century (except Albania), gave the opportunity to think about the fact that ‘Yugoslavia’ - pre- and post-Tito’s Federation - can be a divisive term.

It also presented specific concepts such as ‘yugo-nostalgia’ and the Serbo-Croat common language. Moreover, several visitors from former Yugoslav countries had the opportunity to dialogue and discuss experiences of the past.

«I hope that the Western Balkan countries feel represented in our exhibition, even though we do not focus on national histories». As the first sentence you hear at the beginning of the visit says:

“As we walk you through the main exhibition, you will notice that we do not tell you the history of every European nation. Instead, we want to explore how history has shaped a sense of European memory and continues to influence our lives today and in the future”.

Read also: S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

After all, the House of European History has one main purpose. «Not to highlight the regional differences, but on the contrary to focus on transnational phenomena that have affected the whole continent, with different impact or forms in different parts of Europe», Bădică underlines.

«I personally think that the exoticization of the Balkans is also a historical phenomenon that I hope we are about to grow out of». It is the museum’s duty «to understand the different histories that have shaped the different regions, but not for making one region - the Balkans from example - stand out as different».

Visitors themselves are also called to play an active role. «I encourage them to look for similar histories of their close or more distant neighbors, instead of looking for what they already know», the curator of the House of European History urges.

Although we were taught in school that our national history is so unique and incomparable, «actually it is quite comparable and sometimes strikingly similar to other countries’ history».

From here we can start building a new narrative of a common past and present. Free of prejudices.

Read also: S2E32. Journey to extinguished countries

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

While discovering the impact of the past on our common present, at our bar, the BarBalkans, we have a soft drink that made the history of Yugoslavia and that is still imbottled in a EU Member State.

The carbonated orange soft drink Pipi is produced by Dalmacijavino since the early Seventies. More precisely since 1971, when it first appeared on supermarket shelves in the Socialist Republic of Croatia and in the rest of the Federation.

Pipi takes its name - and image - from the famous Pippi Longstocking, the protagonist of the homonymous children’s novel by Swedish author Astrid Lindgren. Although stylized and refined over time, the girl with blond braids is the trademark of the most famous Croatian soft drink.

Pipi also won the heart of swimmer Veljko Rogošić - the current holder of the world record for longest distance ever swum in open ocean without flippers - who participated in early TV commercials and in curious marketing operations.

For example, the great Dalmacijavino’s great prize game in 1975, when Rogošić threw hundreds of Pipi bottles containing prize vouchers into the sea, for anyone lucky enough to see one make it to shore.

In 1979, the Mediterranean Games were hosted in Split and Pipi was chosen as the official drink. The record of production dates back to that year, with 12 million bottles filled with Pipi.

Over the years, more different drinks have been produced under this label - lemonade, cola, blood orange, tonic - but only the orange carbonated soft drink has entered the collective imagination throughout the Balkans, when ordering a Pipi.

Read also: Cockta, the spomenik of Balkan soft drinks

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 5th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

If you have a proposal for a Balkan-themed article, interview or report, please send it to redazione@barbalcani.eu. External original contributions will be published every last Friday of the month in BarBalkans - Open bar section.

Your support is essential to realize all that you have read. And to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone.

An independent project like this cannot survive without the support of the readers. For this reason I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating:

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans - right in that month - 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of BarBalkans - Podcast on Spreaker and Spotify.