May 1994.

As the tragedy of the 26-day siege of Goražde takes place, a narrow coalition of international powers - the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and Germany - forms a Contact Group whose aim is to make the Bosnia and Herzegovina peace process faster [you can listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast here].

The ultimate goal of seeking preliminary agreement on peace - to be imposed at a later stage on the warring parties - immediately clashes with the failure of a truce considered the first step to reach a definitive solution.

After the end of clashes with Bosnian Croats, Bosniak troops disengaged from Central Bosnia launch a counterattack to break the Brčko Serb corridor between Northern and Eastern Bosnia.

Despite the disparity of forces and armaments on the ground, this ambitious war plan shows the unity between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats not only on a political level, for the first time after the peace in March.

Signs of unity

With the offensive on Brčko, the Bosnian government is trying to rebalance forces on the battlefield, in order to get a stronger position at the peace negotiating tables.

Brčko is located in Northeastern Bosnia, on the border with Croatia (north) and Serbia (east). More specifically, this is the crossing point between Belgrade, the capital of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and Banja Luka, the de facto capital of Republika Srpska.

Breaking the Brčko corridor would allow to disrupt not only supplies sent by the Serbian President, Slobodan Milošević, to his Bosnian Serb counterpart, Radovan Karadžić, but also the territorial continuity between Serb conquests in the north and east of the country.

This is how the Bosniak and Bosnian-Croat armed forces launch a joint and coordinated attack against the Bosnian Serb army precisely in Brčko, for the very first time since the peace between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina signed on March 18 in Washington.

Although the offensive does not fully achieve the desired result - a portion of the Brčko corridor still remains under Serb control - this is the first demonstration of the solidity of the newly formed Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

To the point that Bosnian-Croat Krešimir Zubak (President of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia since February) becomes the first President of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina on May 31.

The understanding between Sarajevo and Zagreb on sending arms from Iran to Bosnia and Herzegovina via Croatian territory also resists. After receiving tacit U.S. consent, the President of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman, initiates a dialogue with authorities in Tehran and secures a 30% commission for the transit of war material.

Iranian weapons and war production machinery also bring a new wave of political influence from the Islamic world on the Bosnian political establishment.

This is the reason for increasingly nationalist intransigence from the Bosnian President, Alja Izetbegović, and his Democratic Action Party against inter-ethnic marriages, Serbian cultural traditions, and ideals of coexistence that have always characterized Bosnian society in general, and the capital Sarajevo in particular.

The Contact Group's Peace Plan

Despite the failure of the proposed truce at the end of April, the Contact Group presents its first draft of the Peace Plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina on May 13 in Geneva.

The new peace plan draws considerable inspiration from the Juppé-Kinkel Plan of November 1993, abandoned within a few months due to increased diplomatic tension between the United States and France.

The Contact Group Plan once again implies the division of Bosnian territory with roughly the same percentages, but only for six months of truce and in two parts (instead of three): 51% to Bosnian Croats/Bosniaks and 49% to Bosnian Serbs.

Upon the permanent end of hostilities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska will federate, keeping the Bosnian State alive through a compromise acceptable to all parties. Including a common Constitution.

The proposal is presented as the last and non-negotiable option. Take it or leave it.

If the Plan is refused, UNPROFOR will withdraw from Bosnia and Herzegovina (a huge risk for Sarajevo) and international sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia will be tightened (with devastating implications for Belgrade).

The scenario outlined by the Contact Group displeases the two opposing leaders on Bosnian territory.

Bosnian President Izetbegović realizes that he has lost the unconditional support of the United States. He is forced to cede to Republika Srpska not only the town of Prijedor in Northwestern Bosnia, but also many others in Eastern Bosnia: Foča, Vlasenica, Zvornik, Rogatica, Bratunac.

Bosnian Serb President Karadžić is furious, because the Plan implies the cession of almost a third of the territories currently controlled by the army of Republika Srpska to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On the contrary, Serbian President Milošević is much more supportive, as he has been looking for months for a way out of a war that is proving catastrophic for the national economy.

Furthermore, the Contact Group Plan would still allow him to claim that the war has been won: half the Bosnian territory is conquered and only a small portion of Greater Serbia is out of the control of ethnic Serbs.

Through a clever change of rhetoric, Milošević can present the result of almost three years of war on Croatian and Bosnian territory as a “small Greater Serbia”. An intermediate stage on the way to achieving the real goal: a “big Greater Serbia”.

However, Milošević is aware of the difficulty of convincing Karadžić, also considering his failure in April 1993 to command respect from him regarding the Vance-Owen Plan. This time, he leaves the mediations to the Contact Group diplomats.

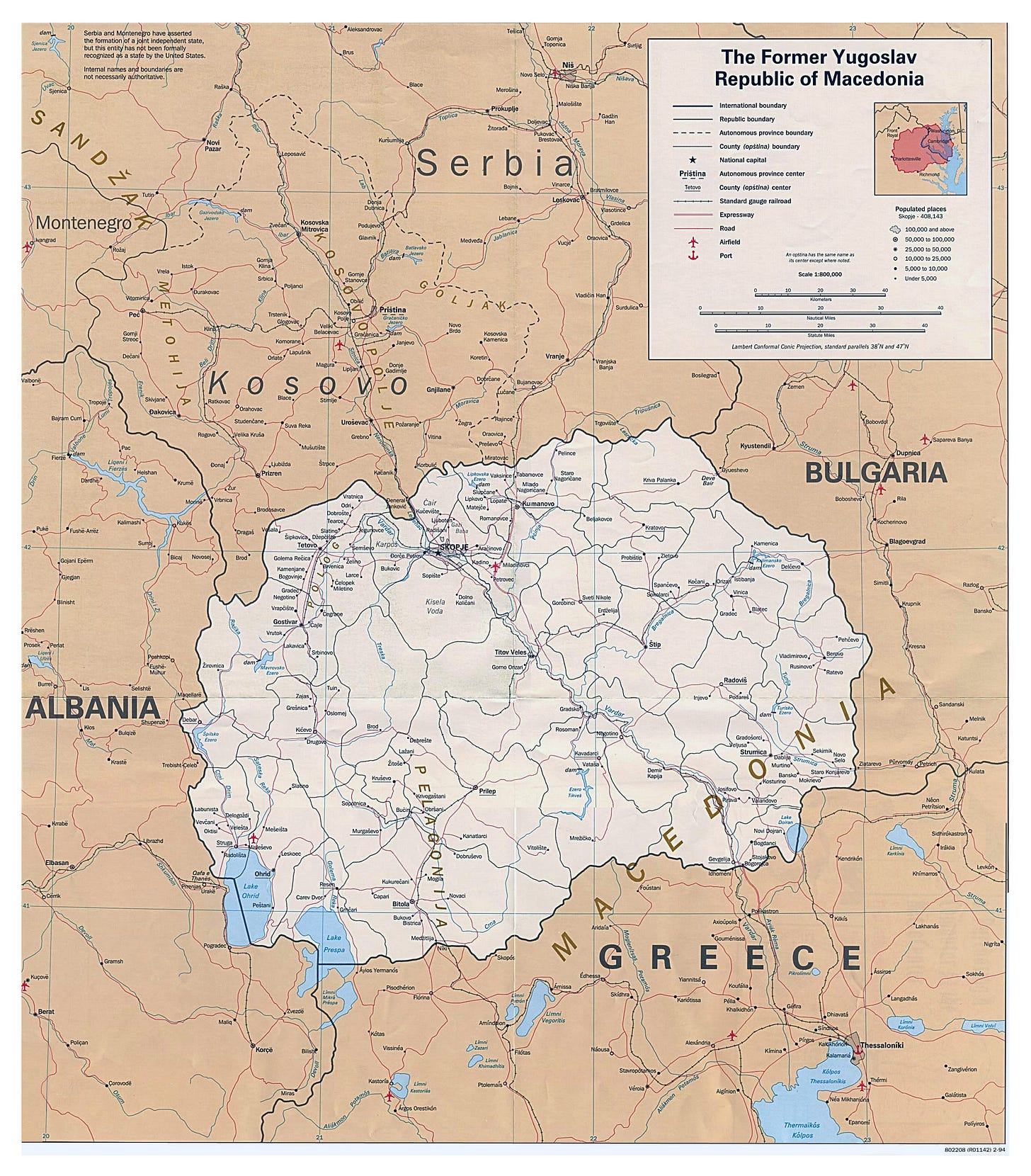

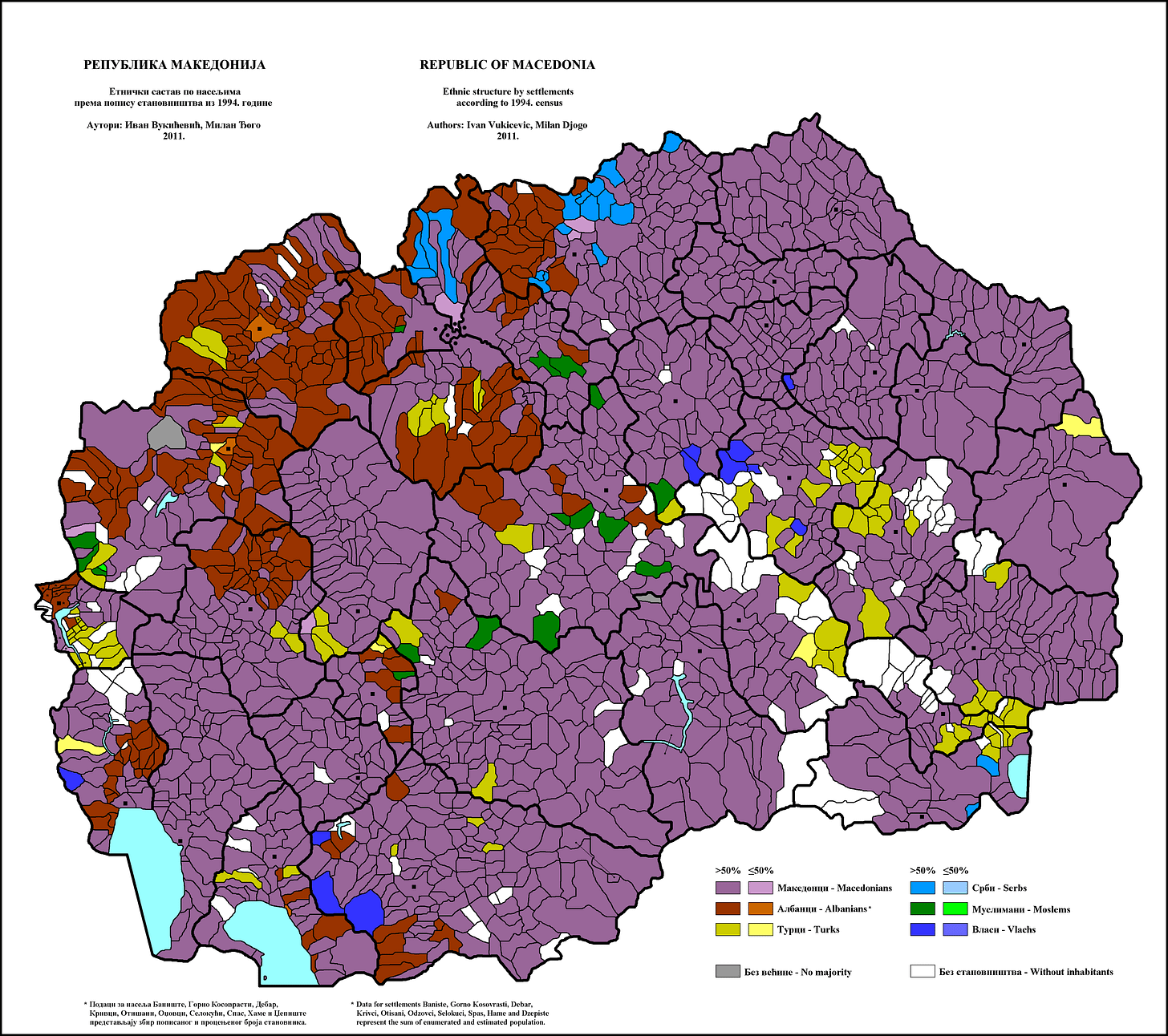

Macedonia’s open fronts

In the meantime, another former Yugoslav Republic is experiencing a moment of serious tension. Not only with its direct opponent on the international stage, but also with the major regional power from which it declared independence in September 1991.

The Republic of Macedonia - or the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), as it is recognized by the United Nations - has been facing opposition from Greece since its inception, particularly regarding the naming issue.

Despite facing the Greek veto on its independence, Macedonia has been a member of the United Nations since 8 April 1993. But the situation in the Republic is so unstable that the United States is forced to intervene with a contingent of soldiers, deployed as part of UNPROFOR.

Nearly half of the entire contingent of more than a thousand Blue Helmets stationed at the former Yugoslav military base in Krivolak comprises U.S. soldiers sent between the fall of 1993 and the spring of 1994 (the others are part of the Nordic battalion from Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Norway).

This substantial U.S. and European military presence is currently preventing the tension along the borders from escalating into a new conflict. Not with Greece, but with Serbia.

As early as January 1992, Milošević - disturbed by the Macedonian independence from Yugoslavia, but not to the extent of provoking war as with Bosnia and Herzegovina - proposed to then Prime Minister of Greece, Konstantinos Mitsotakis, a partition of Macedonia and the creation of confederal ties between Serbia and Greece.

The proposal was rejected, but Belgrade’s attention to the southern front has remained high. This is primarily due to the flow of arms and smuggled goods to Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the ties between the ethnic Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia.

Between May 11 and 12, Yugoslav troops mass on the Macedonian border, which is not defined by any official treaty for 80% of its length (270 kilometers).

Over the following days, Serbian soldiers continue to illegally cross the border, as confirmed by the UNPROFOR commander in Macedonia, Norwegian General Tryggve Tellefsen. He also raises a worrying alarm: the Blue Helmets would not be able to prevent a full-scale conflict between Belgrade and Skopje.

The support of readers who every day gives strength to this project - reading and sharing our articles - is essential to realize all that you have read and listened to, and even more.

If you know someone who can be interested in The Yugoslav Wars podcast, why not give them a gift subscription?

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support BarBalkans will be able to elaborate new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

Here is the archive of The Yugoslav Wars:

Here you can find a summary of the past years:

Share this post