January 1994.

Year 1993 in former Yugoslavia ended with constant bombing on Sarajevo and the failure of the latest peace plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Juppé-Kinkel Plan [you can listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast here].

When the deadlock is likely to remain among the three warring parties - Bosniaks, Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats - the U.S. President, Bill Clinton, unexpectedly takes the lead on the diplomatic level.

The risk is to be perceived as powerless in the face of the war in Bosnia. But also that division of Bosnia and Herzegovina into three entities will result in the creation of a Greater Serbia, a Greater Croatia and a Greater Albania. This scenario would be very unwelcome to the United States.

An obscure triangle

Under pressure from U.S. diplomacy (supported by German and Austrian governments), Bosnian Deputy Prime Minister, Haris Silajdžić, and Croatian Foreign Minister, Mate Granić, meet in Vienna on January 4.

Deputy Prime Minister Silajdžić reassures his counterpart that no harm will come to 65 thousand Bosnian Croats trapped in the Lašva River Valley (in Central Bosnia). Minister Granić promises that no troops from Zagreb will be sent in support to the Croatian Defense Council.

This is the preview of the following meeting between the President of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Alija Izetbegović, and the President of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman. On January 9 in Bonn (Germany), the two leaders discuss a plan for the end of hostilities and for the future of Bosnian territory.

Although Izetbegović cannot accept the idea of a division of Croat- and Bosniak-majority territories from those controlled by Bosnian Serbs, he starts a dialogue with Tuđman on a future monetary union between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

However, a channel of dialogue is still open between President Tuđman and his Serbian counterpart, Slobodan Milošević, following the intense discussions that led to the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan in summer 1992 (even if it was abandoned in early autumn).

The result of this dialogue is the decision to open respective diplomatic offices in Belgrade and Zagreb, the starting point of a possible mutual recognition. Republika Srpska and the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia do the same in Pale and Mostar, respectively.

Meanwhile, civilians on Bosnian soil continue to die, day after day.

On January 22, four shells hit Alipašino Polje neighborhood in Sarajevo, killing six young boys. The number of children killed or missing during the siege of Sarajevo since April 1992 reaches 1,500. Four more children die in Mostar the following day.

On January 28, three Italian journalists working for RAI-TV are killed by mortar fire from Bosnian Croat soldiers in Bosniak sector of Mostar. More than 60 journalists have already been killed since the beginning of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the same number of all journalists killed during the 20 years of the Vietnam War.

The crisis between Europe and the U.S.

The disagreement among Western allies increases together with the U.S. diplomatic initiative and with the difficulties within the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).

Firstly, Thorvald Stoltenberg resigns as Special Representative of the Secretary General. And then, a controversial NATO Summit takes place in Brussels on January 10-11.

The United States is pushing to include in the final declaration a new threat of NATO air strikes to Bosnian Serb positions, if they continue to bomb Sarajevo, to block UNPROFOR soldiers in Srebrenica and to prevent the reopening of Tuzla military airport.

However, this threat is undermined by the United Kingdom (and Canada, that fears repercussions for Canadian Blue Helmets in Srebrenica). In the final declaration there is no detail on the timing and modalities of intervention.

President Clinton warns the European allies that the credibility of the whole Atlantic Alliance will depend on the solution of the war in Bosnia.

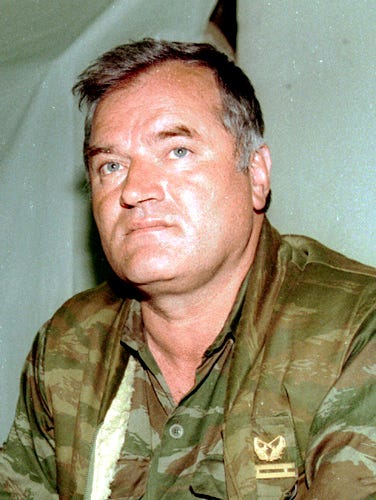

It is no coincidence that Bosnian Serb troops led by Ratko Mladić do not take NATO threats seriously. On January 13, on the occasion of the Orthodox New Year, they bomb Sarajevo heavily. Nine people die during the attack.

While the Republika Srpska army Chief of Staff accepts the replacement of Blue Helmets in Srebrenica (Canadians are replaced by Dutch soldiers), he refuses the truce in the Bosnian capital city - that would allow the general power plant to be repaired - and also the reopening of Tuzla military airport.

The military answer by the Republika Srpska army increases the tension between two sides of the Atlantic.

On January 21, U.S. Secretary of State, Warren Christopher, visits French Foreign Minister, Alain Juppé, in Paris. He tries to persuade the France to join U.S. call for lifting the arms embargo on the government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (as stated by the UN resolution of December 1992).

On the other hand, Minister Juppé wants the U.S. to pressure authorities in Sarajevo to accept his dying peace plan (presented in late November with his German counterpart, Klaus Kinkel).

Both politicians reject the proposal of their respective counterparts. And the French government accuses the U.S. administration of being the main obstacle to a solution to the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

A harsh response from Washington comes a few day later. As the United States Senate approves the resolution authorizing the White House to send arms for self-defense to the Bosnian government, U.S. senators accuse European governments of an «idiotic attitude» in handling the crisis in former Yugoslavia.

An independent project like this cannot survive without the support of the readers. To realize all that you have read and listened to, and even more.

If you know someone who can be interested in The Yugoslav Wars podcast, why not give them a gift subscription?

Here you can find a summary of the past years:

Share this post