It is September 1991.

War in Croatia is a reality, from Krajina to Slavonia.

Since August 19 all doubts have been swept away by the siege of Vukovar, a strategic city on the Danube’s Croatian bank [you can listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast here].

Belgrade can rely on both the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) and paramilitary units, against the disbanding Croatian National Guard.

However, the brutality shown by the Serbs has reached consciences in Brussels. The twelve Foreign Ministers of the European Community (EEC) speak out against the federal government.

They try a way to find peace.

But Serbs know very well how to double-cross them.

A (non) peace plan

The premise is that there are no conditions for peace in the Balkans.

Despite the truce, on September 1 Petrinja is bombed by the MiG and conquered by the JNA tanks.

The Baranja region - in Eastern Slavonia - is now part of Greater Serbia.

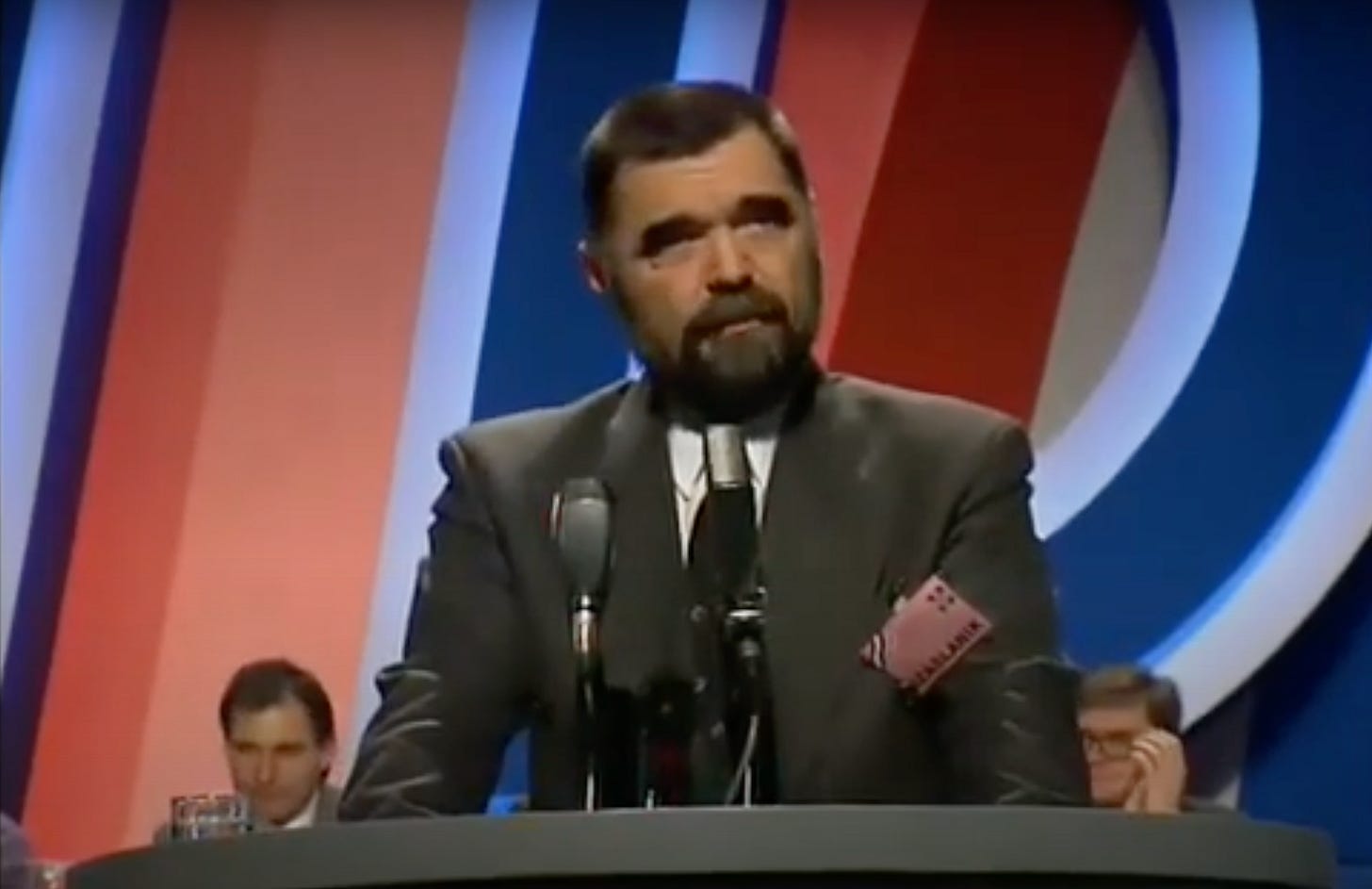

However, the European Community decides to launch a conference, chaired by the British Conservative politician, Lord Peter Carrington.

The Peace Conference on Yugoslavia is opened in The Hague on September 7 and it sets the ambitious goal of securing peace within two months.

The Conference is attended by the members of the collective federal Presidency, the federal government, the Presidents of the six Socialist Republics, the twelve EEC Foreign Ministers and the President of the Council of Europe.

The first consideration is that the Serbian aggression of Croatia is part of a civil war, in which contenders are equally right and wrong.

The consequence is that the issue cannot be resolved with border changes taken by force and that no Republic can aspire to sovereignty without an agreement with the other five.

The Bosnian issue is also addressed. The proposal is to create three Republics, in order to let Serbs reconnect with Belgrade and Croats with Zagreb. But the Twelve oppose the possibility to give birth to a Muslim State in the Balkans.

After five days of negotiations, a Declaration of intent is signed on September 12.

The document highlights the commitment to respect the rights of minorities and not to resort to violence to change national borders.

The promises are contradicted by facts.

And not just in Croatia.

Just one day after the opening of the Conference, a referendum on independence is held in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.

On September 8, 95.26% of Macedonian voters are in favor of separating from the Socialist Federal Republic (the turnout is more than 75%).

Independence is declared on September 25.

Kiro Gligorov becomes the first democratically elected President of the Republic of Macedonia.

In this case, there is no resistance from Belgrade. Greater Serbia has no piece of land to claim in Macedonia. This is why relations with Skopje remain good and they recognize each other.

On the contrary, on the same day of The Hague Declaration military operations extend into the territory of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the first time.

On the southern border with Croatia - thirty kilometers from Dubrovnik - the city of Trebinje falls into Serbian hands on September 12.

This event gives a jolt to the Bosnian President, Alija Izetbegović, to overcome the idea that «choosing between Tuđman and Milošević is like choosing between leukemia and brain tumor».

It is now clear that the plan implemented in Croatia is about to be reproduced in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well.

The ranks of local militias swell with the arrival of Serbian and Montenegrin reservists and with the paramilitary units. In particular, Arkan’s Tigers and Vuk Drašković’s National Guard, as they are marching upon Dubrovnik.

On September 16, following the Croatian example, the Autonomous Region of Bosnian Krajina is born, as «indivisible part of federal Yugoslavia».

In The Hague, Izetbegović only obtains the promise that international observers will also be sent to Bosnia.

Double game in Belgrade

To tell the truth, someone in Belgrade denounces the Ram Plan to annex the territories claimed by Greater Serbia.

Stipe Mesić, the President of Yugoslavia. He is the last one who still believes he can stop the Army and the Serbian President, Slobodan Milošević.

He gives it a desperate try. Without consulting his colleagues in the collective Presidency, on September 11 Mesić orders the Federal Secretary of People’s Defense of Yugoslavia, Veljko Kadijević, to withdraw the troops.

The answer is mocking: the federal President should know that the powers of supreme commander belong to the collective federal Presidency.

Meanwhile, the Waterloo of European mediators continues.

Serbs conquer two crucial points. In the north, the Belgrade-Zagreb highway between Okučani and Nova Gradiška. In the south, the Maslenica bridge near Zadar.

The communications between the Croatian capital city and the regions of Dalmatia and Slavonia are cut.

The Croatian President, Franjo Tuđman, now reacts.

On September 14, he orders the blockade of the federal barracks, cutting off all supplies and providing the Croatian National Guard with weapons and ammunition.

A week later, he lays the foundations of a strategic defense of the territory, with the creation of the Army General Staff.

Croatian paramilitary units also appear on the battlefields: the Zebras, the Black Legions and the Croatian Defense Forces.

They are between 10 and 15 thousand men, who wear the Ustasha (Croatian fascists) black uniforms and - like their Serbian “colleagues” - commit atrocities especially on civilians.

Facing the new escalation of violence, the United Nations Security Council declares that Yugoslavia is «a threat to international peace».

On September 25, Resolution 713 is unanimously approved. The axe of the «general and total embargo on all supplies of arms and war material» falls on Yugoslavia.

This is the Kansas City Shuffle of the Serbian government.

In the Kansas City Shuffle, the scam victim expects to be cheated and believes themselves smart enough to pinpoint where the perpetrator’s move will come from.

But everything is already planned.

This is what happens in Belgrade. Perhaps for the first time in history, a country welcomes happily a punitive measure.

Resolution 713 freezes the possession of weapons of the warring parties. In practice, it favors Serbia, which controls the federal Army and the war industry.

Croatia and the Republics that oppose the Serbian hegemonism are denied the right to self-defense, enshrined in Article 51 of the UN Charter.

On the battlefield, the Serbian double game gives the expected results.

Reinforcements for the siege of Vukovar come from Osijek, while in Dalmatia the siege of Dubrovnik begins. The UNESCO protection of the “Pearl of the Adriatic” is worth nothing.

There is also time to get rid of the cumbersome presence of Mesić, who has tried to save Dubrovnik with letters sent to the UN, to the United States and to the European governments.

In a sitting he cannot attend, on September 25 (once again the dates overlap) the representatives of Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Vojvodina in the collective Presidency oust him.

The vice-president, the Montenegrin Branko Kostić, approves the termination of Mesić’s mandate as representative to the UN Assembly.

In addition, the four representatives abolish the constitutional provision that required the federal Presidency to take decisions by an absolute majority. They apply the simple majority of those present - coincidentally - in Belgrade, where they can only meet because of state of the emergency.

The collective Presidency also assumes the functions previously exercised by the Parliament of Yugoslavia.

This is enough for Brussels. The twelve Foreign Ministers announce that they will not recognize the decisions of an assembly that no longer represents the entire Federation.

They are implicitly admitting the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

If you liked this article, you can spread this parallel journey and the free weekly newsletter on social media:

You can also give a gift subscription to whoever you want. Don’t let this virtual trip to the Balkans get lost!

Here is the archive of BarBalkans - Podcast:

Share this post