February 1994.

Under the push of U.S. diplomacy, the governments of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are beginning to talk about a possible common and peaceful future [you can listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast here].

This diplomatic offensive also opens major disagreements between Europe and the U.S. France is still betting on the dying Juppé-Kinkel Plan, while the United Kingdom undermines NATO toughest threats against the Bosnian Serb army led by Ratko Mladić.

In any case, the road is now drawn for authorities in Zagreb and Sarajevo. But another tragedy in the Bosnian capital has yet to come.

The aftermath of a massacre

The season of massacres in Sarajevo starts again on February 4, when three mortar shots hit a group of people queuing for bread in Dobrinja neighborhood. Ten people die, including three children.

The following day another mortar shot causes an even greater massacre, that recalls 27 May 1992 for location and dynamics. On February 5, around 12:30 p.m., Markale market in the city center is hit again.

Sixty-eight people are killed and 197 wounded. This is the worst massacre of civilians since the beginning of the siege of Sarajevo. The Bosnian Serb besiegers deny any responsibility and accuse the besieged Bosniaks of staging the tragedy, in order to force the lift of international arms embargo on the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Again, the power of the images broadcasted all over the world causes the so-called “CNN effect” (from the US all-news TV channel).

The U.S. President, Bill Clinton, does not exclude any measure in response to the massacre. With the support of France and the United Kingdom, the United States urges UN Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, to ask NATO Secretary General, Manfred Wörner, to activate the “double key”.

In other words, the joint process to order air strikes against Bosnian Serb artillery positions around Sarajevo, in order to prevent further attacks.

On February 9, the NATO Council gives the green light to an ultimatum for an attack within 20 kilometers around Sarajevo, if the besiegers do not withdraw their weapons or hand them over to the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).

Even if the Western diplomacies cross the line between ‘peace keeping’ and ‘peace making’, at the same time they are trying not to humiliate the Bosnian Serbs. Pale, the capital of Republika Srpska, is excluded from the demilitarized area, and the U.S. promise to push the Bosnian government to accept the tripartition of the Republic.

However, all this is not enough to placate Bosnian Serb commander Mladić, who opposes any ultimatum. His arrogance is justified by the support he gets from Moscow.

After the triumph of nationalist and communist forces in the December 1993 general elections, some Russian politicians such as the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, Vladimir Žirinovsky, travel from Moscow to Belgrade, Pale and Knin to advocate for «a union of Slavic States from Vladivostok to Krajina».

Žirinovsky even claims that a NATO air attack on Bosnian Serb positions around Sarajevo would be «a declaration of war on Russia» and «the beginning of World War III».

Although this is not the official political line of the Kremlin, the President of the Russian Federation, Boris El’cin, is forced to adopt a more intransigent foreign policy towards the Western countries, under the increasing pressure of the “red-brown” opposition in the country.

In any case, the political impact of the Markale massacre is not affected by this relation with Belgrade, and there is still a strong willingness in Moscow to work together with the Western allies to resolve the Bosnian issue. President El’cin himself proposes the establishment of a summit between Heads of State and Government of Russia, the United States, France, the United Kingdom and Germany on February 24.

The ultimate goal is to draw up a document with a «historic significance» to put an end to the wars that have been bloodying the Balkans for nearly three years, thanks to the diplomatic cooperation between Moscow, Washington and the European partners.

Peace between Sarajevo and Zagreb

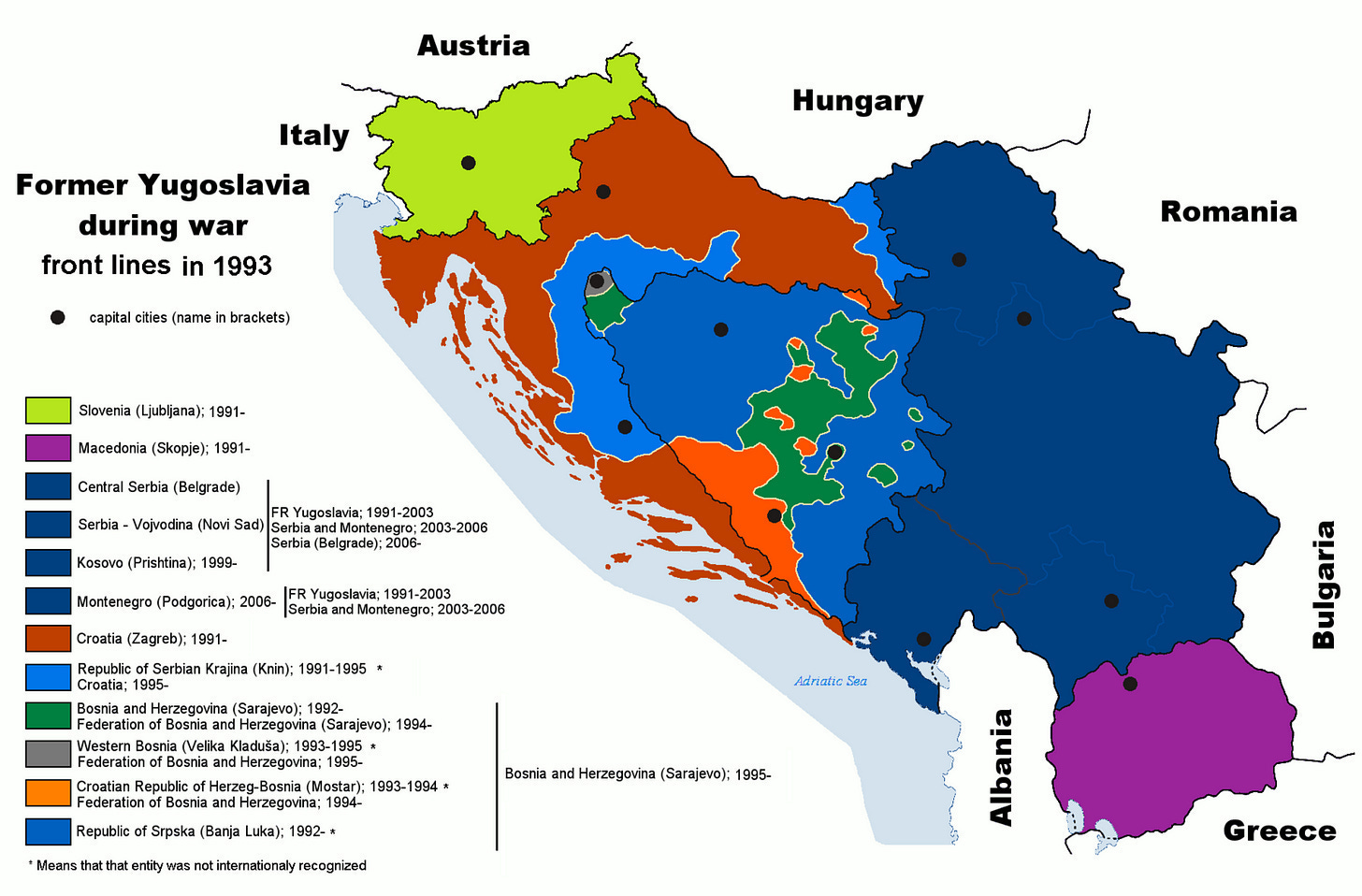

The rapprochement between Moscow and Belgrade also has another effect. The dialogue opened in January between the governments of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina is supported by all diplomatic actors interested in a pacification between the two warring parties.

The Vatican City State, the Croatian Catholic Church, Germany, the United States, Turkey.

On February 17, the international community presents a draft project for a federation between Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, pushing the President of Croatia, Franjo Tuđman, to renounce the long-established dialogue with his Serbian counterpart, Slobodan Milošević, over the partition of Bosnian territory.

If he accepts, authorities in Zagreb could gain support for the reconquest of Krajina region and funding for the economic recovery of the country. On the contrary, a refusal could cost the economic sanctions threatened for a year by the UN Security Council.

This is how Tuđman agrees to the Washington-sponsored project on February 21, also considering the collapse of the Croatian Defense Council in Central Bosnia.

The military defeat has already had heavy consequences on the political establishment of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia. On February 8 in Livno, President Mate Boban is forced to resign and is replaced by the moderate Krešimir Zubak.

What happens in Mostar consequently pushes Croatia to accept U.N. control on its borders with Bosnia and Herzegovina, renouncing any plans to annex Herzegovina.

Two days after Tuđman’s green light to the project of a federation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the commanders of the Bosnian army and the Croatian Defense Council sign the cease-fire, providing a stable foundation for peace on the ground.

This is how a war project that lasted a year and a half ends. Since July 1992, it caused the death of more than 10 thousand people, and it forced nearly half of the 880 thousand ethnic Croats living in Bosnia and Herzegovina to leave their homes during the Bosniak counteroffensive.

Demilitarizing Sarajevo

The U.S. diplomatic offensive considers also Serbia, in order to reach a peaceful solution in the entire Balkan peninsula (including the recognition of Macedonia, almost a year after joining the UN).

The refusal by the President of Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, to withdraw heavy weapons from the heights above Sarajevo makes NATO bombardment on Bosnian Serb positions increasingly real. Almost 200 aircraft are on alert at Italian and French bases, and on three aircraft carriers in the Adriatic Sea.

The Russian President averts this risk, proposing to Milošević to station 400 Russian paratroopers in the demilitarized area around Sarajevo.

On one hand, this compromise avoids escalation of violence between NATO and Belgrade (Milošević agrees to the plan on February 17), but on the other hand it reinforces Russia’s ambiguity towards Serbs and Bosnian Serbs.

Entering Pale on February 20, Russian paratroopers are welcomed as liberators by a cheering crowd. And they salute back “Serbian-style” - with three fingers raised (thumb-index-middle fingers) and the others closed - a religious salute borrowed from the Cetnik militias (the ultra-conservatives Serbs).

Moreover, Bosnian Serbs are allowed to move mortars from Sarajevo to other war fronts, while the Bosnian government is forced to hand over arms to UNPROFOR.

As a result of this reorganization of weapons, Mladić’ troops launch a heavy offensive on Bihać (in Northwestern Bosnia) and on Tuzla, Olovo, and Maglaj in Eastern and Central Bosnia.

NATO immediately wants to make the new balance of power crystal clear. On February 28, two F-16 fighter jets shoot down four Soko G-4 Super Galeb jets of the Yugoslav Army in the skies over Banja Luka, because of the violation of the no-fly zone in Novi Travnik and Bugojno.

Since U.N. Security Council Resolution 816 authorized «all necessary measures» to make the ban on military flights in Bosnian airspace effective, the no-fly zone has been violated 816 times in 334 days.

NATO’s baptism of fire follows an attempt by Belgrade to understand the seriousness of Western intentions and to drive a wedge between Washington and Moscow. But this time the legitimacy of NATO military action is not challenged by the Kremlin.

The support of readers who every day gives strength to this project - reading and sharing our articles - is essential to realize all that you have read and listened to, and even more.

If you know someone who can be interested in The Yugoslav Wars podcast, why not give them a gift subscription?

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support BarBalkans will be able to elaborate new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

Here is the archive of The Yugoslav Wars:

Here you can find a summary of the past years:

Share this post