S5E21. Was it really the worst car in history?

Thanks to the Yugoverse project, the iconic Yugo continues to challenge its undeserved reputation. More importantly, it connects the values of the past with today’s ongoing struggle for a common good

Dear reader,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter with blurred boundaries.

They called it ‘the worst car in history’. It was mocked—particularly for its affordability and accessibility. Critics often likened it to the failure of the socialist state, as if the car itself were a metaphor for the system.

Yet the Yugo is still here. Nearly 50 years after the first model rolled off the production line, it can still be seen on the roads between Serbia and Croatia, climbing mountain tracks in Bosnia, or navigating the streets of Mitrovica, Skopje, Banja Luka, Podgorica and Novi Sad.

The Yugo is undoubtedly a central piece of Yugoslav history—but it is more than that. In recent years, it has increasingly become a symbol of the revival of a collective memory that the political elites of post-Yugoslav states sought to suppress or erase, whether for reasons of nationalism or as a response to a traumatic past.

In short, the Yugo represents far more than Yugoslav socialism—starting with its name. Contrary to popular belief, ‘Yugo’ is not an abbreviation of ‘Yugoslavia’.

Today, Jovana Ninković, founder of Yugoverse—a Belgrade-based company that offers guided tours in vintage Yugoslav cars—share with BarBalkans all her knowledge and insights on this extraordinary car.

Read also: XXVII. New Year’s Eve with Tito

BarBalkans is a newsletter powered by The New Union Post. Your support is essential to ensure the entire editorial project continues producing original content while remaining free and accessible to everyone.

The wind car

“The Yugo is a legend,” says Ninković without hesitation, referring to the car produced from 1981 by the Zastava car factory in Kragujevac, Serbia. The factory had collaborated closely with the Italian company Fiat since 1953.

“Zastava and Fiat have been partners since the very beginning of the vehicle production in Kragujevac,” she explains. Today, the Fiat 500L is still manufactured at the same plant—although no longer under Zastava, which ceased operations in 2008.

While the early models were “were almost exact copies of their Italian counterparts”—thanks to licences granted by Fiat to its Serbian partner (Zastava 750 & Fiat 600, Zastava 101/128 & Fiat 128)—the Yugo was different.

“It was not a ‘carbon copy’ like the others, but rather designed in Serbia,” Ninković notes. What also set it apart was that “all the components were produced in Yugoslavia”, across the different Republics: interiors and brakes in Croatia, seat belts, locks and mirrors in Macedonia, electrical systems in Slovenia, engines in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and final assembly in Serbia.

And then there is a curious detail that few people know, as Ninković reveals.

“The name ‘Yugo’ did not derive from ‘Yugoslavia’, that is a common misconception. As you can see on some of the first series of the car, the original name was ‘Jugo’. It was named after the warm, dry wind that blows from Africa and becomes humid over the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, “it was common to name new car models after types of wind.” Examples include the Volkswagen Scirocco, the Maserati Ghibli (the Libyan name for the same wind), and the Zastava Jugo—later renamed Yugo—“which means scirocco” in Serbo-Croatian.

Read also: S4E17. Balkan sombreros

The first prototype of the Yugo was built on 2 October 1978, with official production beginning on 28 November 1980. Sales began the following year.

According to Ninković, one of the car’s defining features was its affordability. It was compact, “yet offered plenty of space for four passengers”, although it wasn’t the easiest car to drive. “In Serbia, we have a saying: if you have learned to drive a Yugo, you can drive anything!”

Other fun facts include the spare wheel located in the engine compartment, versions with air conditioning, and around 500 Yugo Cabrio models designed in Detroit by General Motors—“mainly for young Americans who wanted a small, affordable convertible with a sporty look.”

The Yugo was “extremely comfortable to drive, and fuel consumption could be significantly reduced if you treated it right.” It also adapted well to modification, thanks to its “very simple engine, compatible with many types of upgrades and swaps”—making it “the most popular among young enthusiasts who wanted to build their own race cars.”

The worst car or the best car

“For such a small car from Yugoslavia, the Yugo has endured a lot,” says the founder of Yugoverse.

It has been described as “reliable, practical and affordable,” but also as the worst car in the world. “Both can be true, depending on what you compare it with and where you come from, but nobody can deny that the Yugo has defied all odds”—as demonstrated by the 140,000 units sold in the United States since 1984.

Even after more than 40 years on the road, Yugos—like those used by Yugoverse for guided tours—“still work perfectly,” Ninković points out. She recalls how “on an average salary, you could afford to buy a new car” that would last a long time—until it eventually broke down. “Spare parts were always cheap, and the simplicity of the car made it fairly easy to maintain.”

Read also: XXVI. The Return of the Great Yugoslavia

Yet the label “worst car in history” has remained attached to the Yugo, largely due to the poor reputation it gained in the United States.

“There, the Yugo never had the chance to be updated or improved because of the political situation in Yugoslavia,” explains Ninković, referring to the dissolution of the Federation and the wars of the 1990s.

As a result, “there weren’t enough authorised repair shops or spare parts—or there were only of a poorer quality—and those who wanted to maintain or repair their cars didn’t know where to turn.” In other words, “the Yugo was simply ‘dropped off’ in the United States, and then everything stopped.”

Although it fulfilled its intended purpose overseas—“it was cheap and affordable, usually the second car for the family”—it is easy to imagine the frustration when maintenance was needed, but no mechanic could help.

Read also: XLIII. The basketball factory

Then there is another issue, related to the wars of the 1990s. After the NATO bombing of the Kragujevac factory (Zastava was also involved in arms production) in 1999, “these cars never had a chance to be updated—they remained stuck in time.”

As a result, Zastava cars continued to be produced unchanged until 2008. For reasons of age and obsolescence, it is clear that, compared to competitors that were 20 or 30 years more modern, “the Yugo couldn’t compete in any way,” recalls Ninković.

All of these circumstances do not justify its poor reputation. And besides, “how many 1980s cars do you still see on the road every day?”

Much more than a small car

In light of a past worth rediscovering, in 2019 Ninković launched Yugoverse—a local tourism project offering people the chance to explore Belgrade and Yugoslav history aboard a Yugo (or other vintage Zastava models).

“The idea that prompted me to found the company was that no one who drives a Zastava should be forced to sell it due to lack of funds to maintain or restore it,” explains the Serbian entrepreneur.

Allowing people to earn money “by driving their beloved cars” while connecting those with shared passions became the key to success: “It was a fusion of our love for cars, history and our city—and the ability to present all that to tourists visiting Serbia.”

Read also: S4E15. The feminist fight of Serbian Gen Z

At a time when the Serbian government is actively erasing traces of the Yugoslav past, the Yugo has become a symbol of something greater.

“Some see it as a symbol of difficult and dark times, a shadow they pretend they have never owned or driven,” says Ninković. But the truth is often quite the opposite: “They were born in a Yugo, learned to drive in a Yugo or owned one—and they have forgotten what it means to love a car like a member of the family.”

What Yugoverse promotes is “respecting and loving your history”—critically, yes, but with a touch of idealism too.

All of this is captured in one word: Yugonostalgia. In recent years, it has evolved into something more than a fond memory of a bygone era. It is a kind of resistance to a model of society that has shed some of the progressive values of the Yugoslav period.

“Yugonostalgia is often seen as a ‘disease’ of some parts of modern society, or as a hundred steps backwards,” says Ninković, “but in truth, we are nostalgic for are core values that have disappeared since then.”

Not just the famous Yugoslav unity—“which was partially honest and partially politically forced”—but more importantly, the sense that “people genuinely worked for their country and their future.”

Read also: S4E18. Rest is resistance

‘Plant a tree so that your children and grandchildren can sit under it, even if you never will’. This, she says, was the kind of philosophy that motivated young people at the time to build roads, schools, homes, parks—entire cities. “Much of what we have in Belgrade today, we owe to them.”

According to Ninković, those ‘affected’ by Yugonostalgia in 2025 are inspired by “commitment, effort, and the conviction that we are building something good and useful”—not just for ourselves, but “for our neighbours, our children, and our grandchildren.”

Today in Serbia, this awareness is regaining strength among a new generation that is “fighting with all its might for a better society.” Students, in particular, “are setting the example by uniting people who have long been divided, but for no irreparable factors.”

It is in this new spirit that Ninković sees the fundamental values of the past: “A spark that illuminates the possibility that we can all work together for a common good,” both now and in the future.

Read also: S5E14. Meet the voices of Serbian students

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of the road.

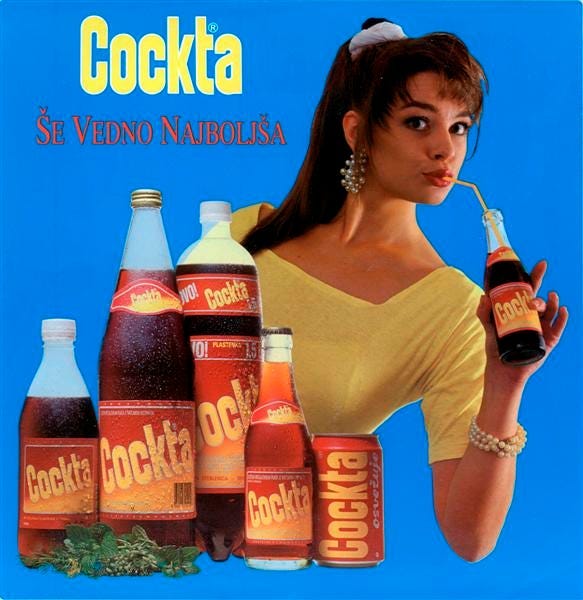

Today at our bar, the BarBalkans, we find a drink that is also suitable for those who need to drive—whether in a Yugo or any other car. “For a non-alcoholic option, definitely Cockta,” Ninković recommends.

Cockta was invented in 1952 in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia as a soft drink designed to compete with foreign brands and compensate for their absence in Yugoslavia, following a government ban.

Ivan Deu, Director of the state-owned corporation Slovenijavino, came up with the idea of creating an original beverage. It was chemical engineer Emerik Zelinka, working in Slovenijavino’s research labs, who developed the formula.

The name derives from the word ‘cocktail’, and the new product was first launched on 8 March 1953 in Planica, during a ski jumping competition. That year, 4.5 million bottles were filled with one million litres of Cockta.

Cockta is still made from a blend of eleven different herbs and spices, with rose hip providing its distinctive flavour.

Read also: S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 22nd and last stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support The New Union Post will be able to elaborate new ideas, articles, and interviews, including within BarBalkans newsletter.

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of The Yugoslav Wars every month on Spreaker.

Discover Pomegranates, the newsletter on Armenia and Georgia’s European path powered by The New Union Post

If you no longer want to receive all BarBalkans newsletters, you can manage your preferences through Account settings. There is no need to unsubscribe from all the newsletters, just choose the products you prefer!