S5E10. The Ghost of 1994 past, present and future

A brief summary of the fourth year of dissolution of Yugoslavia, exactly 30 years ago. Month by month, the timeline of the events with BarBalkans' podcast, discovering the fate of the European history

Dear reader,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter with blurred boundaries.

On the occasion of the last episode of 2024, our tradition is to look back over the past year with BarBalkans’ time machine.

If you are familiar with BarBalkans, you already know it. If you have recently joined us, you will discover it soon. Alongside the biweekly newsletter, there is a parallel path following the dissolution of Yugoslavia 30 years ago.

Month after month, The Yugoslav Wars podcast is taking us back in time, to the decade that sealed the fate of recent European history.

To kick off 1995 (or rather 2025) together, all you need to do is a small donation.

Every second Wednesday of the month, you will receive an email–only for subscribers–with the story of what happened in that very month 30 years ago.

Today, we rewind the tape and discover the highlights of this year.

1994.

There is a new way to support BarBalkans.

By donating a coffee worth €1, you can help make this editorial project sustainable. You can also become a member with €5 per month.

Visit buymeacoffee.com/newunionpost

The fourth year of war

In this newsletter you will find the link to each episode. The text content is reserved to subscribers, but here you can get an overview of the events. You can freely listen to all the podcasts on Spreaker and Spotify.

The year 1993 ended with the relentless bombardment of Sarajevo, the nationalists’ victory in Serbia’s parliamentary elections, and the clear failure of the Juppé-Kinkel Plan, the latest attempt at peace for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In January, President of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegović and President of Croatia Franjo Tuđman establish initial contacts to discuss a cessation of hostilities and the future territorial organization of Bosnia. Despite this, Tuđman continues to maintain dialogue with Serbian President Slobodan Milošević.

As international diplomacy stalls, strained by tensions between Paris and Washington, the war in Bosnia rages on. In February, one of the war’s darkest moments take place in Sarajevo’s Markale market: a shell strikes the crowd, resulting in the highest civilian death toll since the siege begins.

The attack shocks global public opinion and prompts Russian President Boris Yeltsin to propose a summit with the leaders of the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany. The goal is to draft a document of “historical significance” to end the wars in the Balkans.

International pressure mounts on Zagreb and Sarajevo. Western allies push Croats and Bosniaks to embrace a federation proposal that can peacefully resolve a conflict. The war has already claimed over 10,000 Bosnian lives since July 1992.

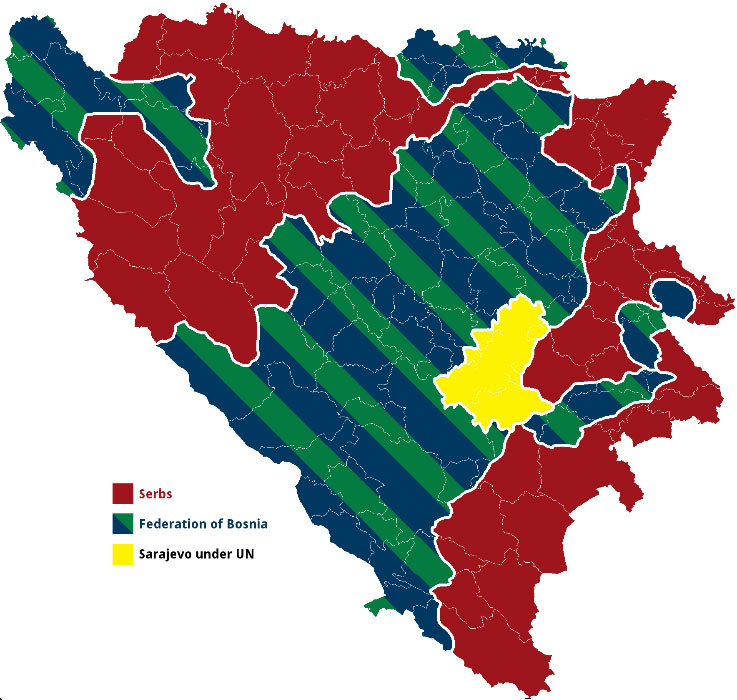

In March, the Washington Agreement establishes the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and paves the way for a potential confederation with Croatia. This agreement marks the end of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia, the secessionist project in Bosnia led by Croatian nationalists.

Despite the devastating toll of war, international sanctions, and out-of-control inflation on Serbia’s economy, President Milošević decides to go on the offensive in the Drina River Valley, targeting isolated Bosniak enclaves: Goražde, Žepa, Srebrenica, and Tuzla.

A fierce assault is launched on Goražde, lasting 26 days until late April. The Serb offensive exposes growing tensions between the UN and NATO over the possibility of targeting the besieging forces.

The North Atlantic Council eventually imposes an ultimatum, leading to a complete Serb withdrawal from a 20-kilometre demilitarised zone around the enclave. However, as in Srebrenica, Goražde’s population is left trapped within the “protected area,” disarmed and vulnerable.

Meanwhile, the international community continues its search for a plan to end the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. After months of diplomatic efforts, the Contact Group—comprising the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany—is established to streamline and accelerate the peace process.

In May, the first draft of the Contact Group Plan revisits the division of Bosnian territory as proposed by the Juppé-Kinkel Plan. The new peace plan simplifies the division into two parts rather than three, allocating 51% of the territory to Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats, and 49% to Bosnian Serbs.

On the battlefield, Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats forge a unity against Bosnian Serb forces near Brčko, a strategically critical area in northeastern Bosnia bordering Croatia and Serbia. Brčko serves as a vital corridor linking Belgrade, the capital of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to Banja Luka, the de facto capital of Republika Srpska.

Cutting the Brčko corridor would sever the supply route from Belgrade to Bosnian Serb President Radovan Karadžić and disrupt the territorial continuity of Serb-controlled areas in northern and eastern Bosnia, dealing a significant blow to their war effort.

The hour of the Bosnian Serbs

From the moment the first draft of the Contact Group Plan is unveiled, Bosnian Serb Karadžić emerges as the greatest obstacle—not only to a peace agreement but also to Milošević’s broader ambitions.

Karadžić fails to understand that the territorial arrangements proposed in the plan could facilitate the creation of a ‘small Greater Serbia’—the union of Republika Srpska with Yugoslavia—as a stepping stone toward the more ambitious vision of a ‘big Greater Serbia.’ His intransigence complicates both the peace process and Milošević’s strategy.

In June, tensions in the Balkans spill over into Macedonia, another former-Yugoslav Republic independent since September 1991. Macedonian President Kiro Gligorov warns that “the danger comes from the north,” citing repeated incursions by Yugoslav troops along a largely undefined border. Over 80% of the 270-kilometre border remains unregulated by any formal treaty.

In July, the Contact Group Plan is formally presented. It requires Bosnian Serbs to cede 22% of the territory under their control, reallocating areas such as the enclaves of Srebrenica, Žepa, and Goražde to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Additionally, Sarajevo is to be designated a United Nations protectorate for two years, while Mostar comes under the administration of the European Union.

The Bosnian Serb Parliament conditionally approves the plan—setting six preconditions and treating it as a basis for further negotiations—but Karadžić advocates outright rejection.

The war continues unabated. On the northwestern front, the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina launches Operation Tiger, targeting Fikret Abdić’s Autonomous Region of Western Bosnia.

By August, almost the entire secessionist enclave is overrun, and Velika Kladuša, its stronghold, falls. Despite Sarajevo’s offer of amnesty to members of the People’s Defense of Western Bosnia, approximately 35,000 civilians and soldiers flee to Croatia, seeking refuge among their allies in the Serbian Republic of Krajina.

Meanwhile, Milan Martić’s Croatian Serb nationalists answer Karadžić’s call to unite Serbian “compatriots” in pursuit of a Greater Serbia, opposing the peace plan.

Milošević reacts decisively. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia closes its border with Republika Srpska (except for essential food and medical supplies), severs telephone lines, and halts diplomatic relations.

However, a referendum on the peace plan in Republika Srpska delivers a decisive rejection, with 96.65% of voters opposing it. This result buries yet another attempt by the international community to broker peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In September, global attention shifts back to Sarajevo as Pope John Paul II announces plans to visit the besieged capital. However, the trip is canceled when the United Nations declares it cannot guarantee the Pope’s safety from what it describes as the threat of “a masked attack, after which the attacker could accuse his enemies.”

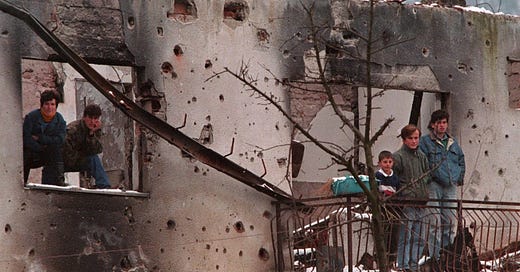

Sarajevo, already crippled by a lack of electricity and gas, now faces a humanitarian crisis as water and food supplies run out. This situation stems from a blockade of humanitarian convoys imposed by the Bosnian Serbs in retaliation for NATO airstrikes on Ratko Mladić’s forces, launched in response to violations of the demilitarised zone around the Bosnian capital.

Meanwhile, bolstered by smuggled weapons from Iran and Turkey, the Bosnian Army goes on the offensive in northwestern Bosnia in October. Simultaneously, the Croatian Defence Council (the Bosnian Croat military force) launches its own attacks.

For the first time in the conflict, a town held by Bosnian Serbs is recaptured. Kupres, strategically located between Bihać and Mostar, becomes a pivotal gain for controlling central Bosnia and western Herzegovina.

At the same time, Bosnian Croat forces prepare an attack against the Croatian Serbs to reconquer Knin, the capital of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina, signaling an escalation of the conflict in the region.

Faced with the existential threat to Bosnian Serbs and Serbs of Croatia, Milošević does not abandon his “compatriots,” despite the political rift of recent months. In November, a massive offensive reverses the situation on the battlefield.

The 5th Corps of the Bosnian Army faces a coordinated attack from Bosnian Serbs in the south/south-east and from Croatian Serbs and Bosniak secessionists in the north/north-west. This offensive includes remnants of the People’s Defense of Western Bosnia, which successfully advances on Velika Kladuša.

Bihać now stands on the verge of collapse. The Bosniak enclave endures relentless bombardment from the Bosnian-Serb army, which deploys napalm and fragmentation bombs. The planes that bomb Bihać take off from Udbina airport, located just across the Croatian border, in the heart of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.

Tensions escalate between the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR)—accused of appeasing the Serbs—and NATO, which advocates for a robust offensive against Serbian positions.

As Serb tanks press closer to Bihać, NATO’s demilitarisation agreement temporarily halts the advance but leaves the balance of power in Mladić’s favour.

An unexpected turn of events occurs in December. The Contact Group approves the ‘Brussels option’ of the peace plan, which would permit Republika Srpska to form a confederation with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, like the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with Croatia.

Moreover, Bosnian Serb President Karadžić suggests former U.S. President Jimmy Carter as a mediator. This initiative leads to an agreement for a four-month ceasefire across Bosnia, intended as a prelude to peace talks based on the ‘Brussels option.’

On 31 December, Sarajevo marks 1,000 days under siege. This is the longest siege in contemporary history, even longer than the siege of Stalingrad during the Second World War.

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road and of this year.

Like every end of the year, we deserve two Balkan specialities to warm up this winter day.

At our bar, the BarBalkans, we find a small glass of hot rakija, one of the most typical Balkan Christmas drinks, very easy to prepare.

And then, there is a cup of kuhano vino, the Balkan mulled wine. The wine is boiled with a combination of nutmeg, cloves, cinnamon, sugar, orange juice and zest.

Let’s continue the BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 11th stop.

A big hug and have a good journey!

If you have a proposal for a Balkan-themed article, interview or report, please send it to redazione@barbalcani.eu. External original contributions will be published in the Open Bar section.

The support of readers who every day gives strength to this project - reading and sharing our articles - is also essential to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone.

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support BarBalkans will be able to elaborate new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

Regardless of what you decide, just thank you.

If you no longer want to receive all BarBalkans newsletters (the biweekly one in English and Italian, Open Bar external contributions, the monthly podcast The Yugoslav Wars for subscribers), you can manage your preferences through Account settings.

There is no need to unsubscribe from all the newsletters, if you think you are receiving too many emails from BarBalkans. Just select the products you prefer!