S5E18. What do we know about Yugoslav partisans in the Italian Resistance?

Interview with historian Eric Gobetti on the experience of prisoners of war and political and civilian internees who, from 1943, fought as foreigners in the war of liberation against Nazi-Fascism

Dear reader,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter with blurred boundaries.

2025 marks a particularly significant anniversary. Across Europe, we will be commemorating 80 years since the liberation from Nazi-Fascism during the Second World War.

Anniversaries offer a chance to reflect—not just on what happened in the past, but on how those events continue to shape our present.

This is especially true of the Resistance. Eighty years ago, it helped lay the foundations for a Europe free from the grip of far-right dictatorships—thanks in large part to ordinary people who stood up to occupation and collaboration.

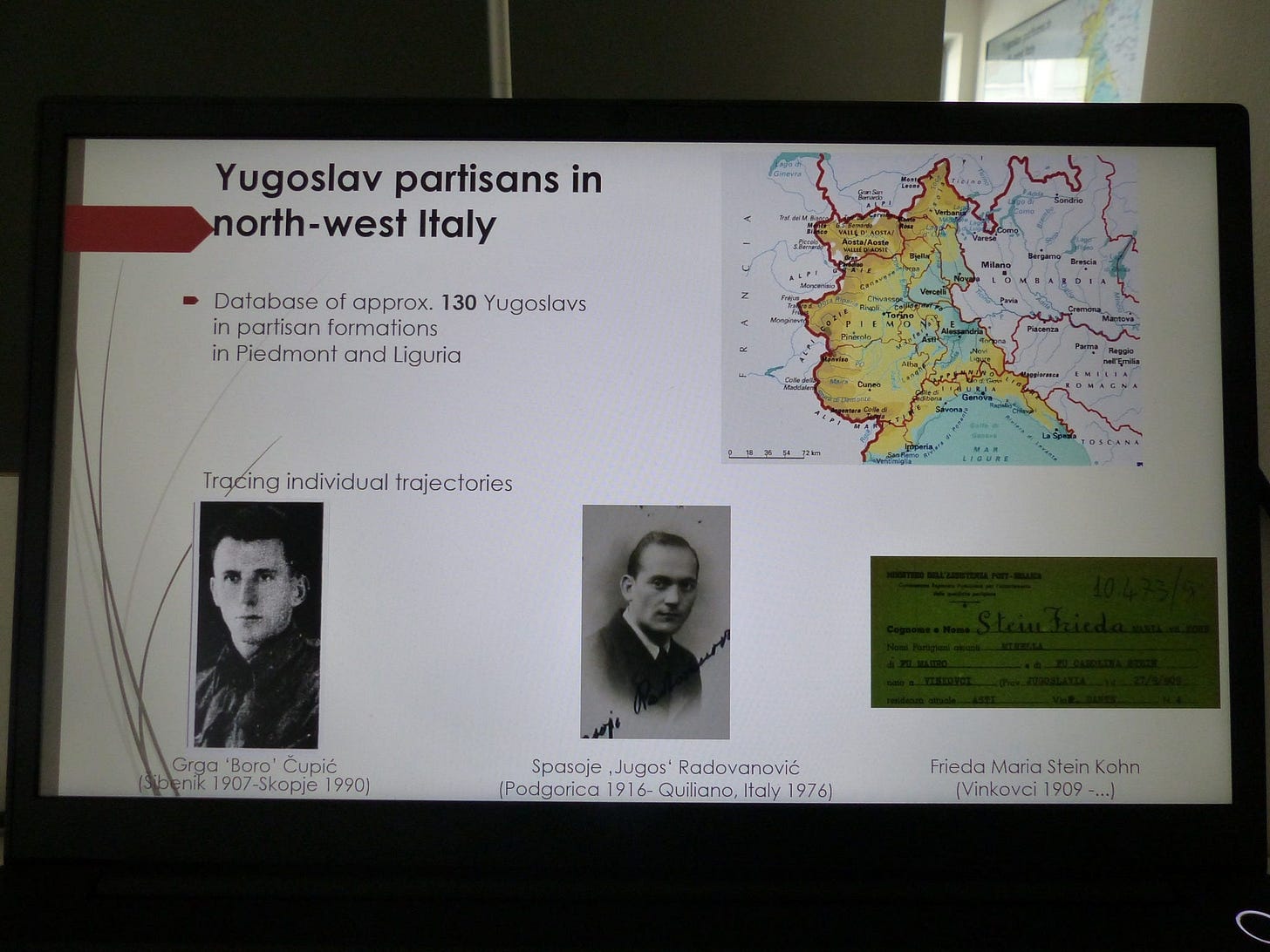

But not all of those who took part in the struggle for liberation have been remembered equally. One of the most striking examples—both for the scale of its contribution and the depth of its neglect—are the Yugoslav partisans who fought in the Italian Resistance.

To uncover the story of these nearly forgotten foreign fighters, BarBalkans welcomes Italian historian Eric Gobetti, a specialist in the history of the Resistance and Yugoslavia, whose work has played a key role in bringing this overlooked chapter of the partisan war back into focus.

BarBalkans is a newsletter powered by The New Union Post. Your support is essential to ensure the entire editorial project continues producing original content while remaining free and accessible to everyone.

Different types of foreign fighters

How did Yugoslavs come to fight in Italy’s war of liberation against Nazi-Fascism?

“The vast majority of foreign partisans in Italy were prisoners before the armistice of 8 September 1943. In the case of the Yugoslavs, this context is particularly significant, and we can distinguish three main categories of internees.

The first group consisted of prisoners of war—soldiers captured in 1941 during Italy’s invasion of Yugoslavia. Some had already been released after being reclassified as nationals of so-called friendly States.

For instance, following the creation of a collaborationist State in Croatia, many Croats were released almost immediately, along with Serbs and Montenegrins who chose to join the fascist-aligned Chetnik movement. Slovenians were also freed once half of Slovenian territory was annexed by Italy.

The rest remained in prison camps, mostly in northern Italy. On 8 September 1943, there were around 20,000 still interned—the vast majority of them Serbs and Montenegrins.

Then there were the civilian internees. Roughly 50,000 Yugoslavs who were deported to Italy during the war (with a similar number held in Yugoslavia). Some had been partisans or supporters, others were civilians living in Resistance areas and were rounded up during anti-partisan operations in 1942–1943.

They were held in camps not only in northern Italy, but also along the eastern border—those deemed ‘less dangerous’, mostly women and children—and in central Italy. In camps like Renicci (Tuscany) and Colfiorito (Umbria), adult men and active partisans were the primary detainees.

Read also: S4E8. You should know who is Valter

The third category consisted of political activists, most of whom were communists. Some had been imprisoned even before the war began. Many were Italian citizens from the eastern border regions—areas such as Istria, Fiume, Capodistria, and Trieste—but were of Slovenian or Croatian nationality.

This raises an important question: what does it mean to be a foreigner in Italy, or an Italian abroad? One particularly striking example is Anton Ukmar, a Slovenian from Trieste and a committed member of the Italian Communist Party. After fighting alongside Ethiopian partisans in the 1930s, he became a partisan commander in the province of Genoa.

After the armistice of 8 September 1943, many of these political activists joined the partisan movement, where they played a significant role in the Resistance. As for the others—both civilian internees and former soldiers—only a minority chose not to return home. Most of those who stayed behind were escapees who found shelter with local farming families in the Alps and the Apennines.”

Their contribution to the Italian Resistance

In which areas of Italy did these Yugoslav fighters operate?

“For both political activists and former military personnel, their presence was scattered—they could be found operating not only in the north, but also in the south of Italy.

Political activists often actively sought out local partisan groups to join. In contrast, former officers of the Yugoslav royal army were generally more conservative and less inclined to engage in partisan activity. However, through personal connections, friendships, or particular local circumstances, some of them were eventually drawn into the struggle, especially when Italian partisans sought them out for their military expertise.

The largest concentrations of Yugoslav fighters were in central Italy, primarily made up of former prisoners from civilian internment camps. The two significant groups were Montenegrins from Colfiorito and Slovenes and Croats from Renicci. Many were either partisans or closely aligned with the Resistance, already convinced of the need to take up arms. Their presence was bolstered by support from political activists, including Slovenians and Croats from the Italian–Yugoslav borderlands.

This combination—of leaders who spoke the languages of the Yugoslav peoples, and large numbers of men with prior partisan experience—made the phenomenon particularly prominent in central Italy.

They were especially active in the Marche region, where they fought in mixed partisan bands—such as the one led by Mario Depangher, which included Afro-descendants, Jews, British POWs, and Yugoslavs—as well as in exclusively Yugoslav units, like the Montenegrin group from Colfiorito. One notable example was the Tito Battalion, later renamed the Gramsci Brigade, which was commanded by a Montenegrin alongside an Italian political commissar.

The Yugoslav partisans typically established immediate connections with local communists, as most had ties to the Communist Party. In some cases, even conservative former military officers ended up fighting in communist units, particularly when those were the only ones active in the area.”

How did this collaboration evolve over time?

“Until 1944, these Yugoslav fighters had no direct link to Tito’s command. Some of the partisans based in Colfiorito believed they were fighting as part of the Yugoslav partisan army, but in reality, they operated under the authority of the local CLN (National Liberation Committee).

Things began to shift in 1944, when the front line moved north from the Gustav Line to the Gothic Line. As central Italy was gradually liberated, many of these fighters relocated south, where they encountered a little-known yet remarkable development.

Between late 1943 and the end of 1944, the region of Puglia became a major logistical hub for the Yugoslav Resistance. This was the result of an agreement between Tito and Churchill, which allowed for the establishment of hospitals, recruitment centres, training bases, and even partisan Yugoslav navy and air force on Italian soil.

Tens of thousands of Yugoslav partisans passed through these centres in Puglia, training there before returning to Yugoslavia to continue the fight.

This is an extraordinary story: partisans who had fought in Montenegro, were captured and deported to Italy, joined the Resistance in central Italy after the armistice, relocated to Puglia for training, and ultimately returned to Yugoslavia to resume the struggle.

In essence, they fought four different wars—yet always through the lens of the same partisan cause.”

What actions should be remembered?

“Two key episodes stand out, both in central Italy.

The first is the Battle of Bosco Martese (Teramo) in September 1943. Here, Yugoslav and British prisoners who had escaped from a nearby camp were surrounded by German forces, but managed to defeat them and force a retreat. It was one of the earliest partisan victories in Italy, and the Yugoslavs played a decisive role.

The second is the Partisan Republic of Norcia and Cascia (Perugia), a strategically crucial area that sat along the route connecting Rome with northern Italy—a vital corridor for German withdrawals. In the spring of 1944, the Gramsci Brigade, composed largely of Yugoslav partisans, liberated the region, seriously hampering the occupying forces. It was the first territory in Italy to be freed by partisans.”

A troubled memory

Why has the history of the Yugoslav partisans faded from the memory of the Italian Resistance?

“Unlike the British, Soviet, or even German and Austrian partisans, the partisan experience was remembered in Yugoslavia as an extraordinary epic—a source of deep national pride. Yugoslavia was not only a multi-ethnic and multi-national state, but also the only country in Europe to liberate itself entirely through its own Resistance movement.

Just as Yugoslavia celebrated the many foreigners who had fought within its own partisan ranks—including Italians and Germans—it was equally proud of its partisans who had fought abroad. This internationalist spirit was a cornerstone of the communist ideology that had shaped the Yugoslav Resistance.

In Italy, however, this chapter was largely left out of the official narrative. For decades, the Resistance was primarily portrayed as a national struggle—Italians against foreign occupiers. The presence of foreign fighters didn’t fit neatly into this framework, especially those from countries viewed with hostility in the post-war years.

Yugoslavia was particularly problematic. Not only was it communist, but it also had ongoing territorial disputes with Italy over the Trieste border until 1954.”

Read also: S4E17. Balkan sombreros

Are we now ready to rediscover this history?

“From a broader European and global perspective, there is growing interest in exploring the international dimensions of Resistance movements, including the role of foreign fighters.

But in Italy, the case of the Yugoslavs remains particularly sensitive—and, paradoxically, the situation may have even worsened. Today, the dominant stereotype casts Yugoslav partisans as brutal aggressors along the eastern border. This image clashes with Italian nationalist narratives and makes it difficult to reintroduce them as figures worthy.

What’s more, while Yugoslavia once actively celebrated its partisan legacy, no successor State today carries that torch. All of them emerged from conflicts that were fought against the very idea of a united Yugoslavia.

This isn’t about deliberate erasure. Rather, this is a case of collective indifference. There is simply little political or cultural will to study, remember or publicise these stories—neither in Italy, nor in the former Yugoslav countries.”

Read also: S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of the road.

Today at our bar, the BarBalkans, we are celebrating the 80th anniversary of liberation from Nazi-Fascism with a rakija in hand and the powerful voice of Goran Bregović, singing the world’s most beautiful anthem of freedom:

“One morning I awakened and I found the invader.

Oh partisan, carry me away, because I feel death approaching […]

This is the flower of the partisan, who died for freedom”.

Read also: S4E13. Gastronationalism tastes like nothing

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 19th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support The New Union Post will be able to elaborate new ideas, articles, and interviews, including within BarBalkans newsletter.

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of The Yugoslav Wars every month on Spreaker.

Discover Pomegranates, the newsletter on Armenia and Georgia’s European path powered by The New Union Post

If you no longer want to receive all BarBalkans newsletters, you can manage your preferences through Account settings. There is no need to unsubscribe from all the newsletters, just choose the products you prefer!