XXIX. When the earth trembles

Petrinja earthquake (Croatia) is the latest in a series of seismic events that hit the Balkans. They are caused by the Adriatic micro-plate, placed between the Italian and the Balkan peninsulas

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the Italian newsletter whose aim is to give a voice to the Western Balkans’ stories, on the 30th anniversary of the Yugoslav Wars.

After last week’s special episode (where a parallel path has begun), let’s start again our journey, still at Tito’s New Year’s Eve.

All of us hope to leave a tremendous 2020 behind. Among the many things that went wrong, an(other) earthquake struck central Croatia in the last days of December, killing at least 7 people.

It was not an isolated incident and it is better to understand the origin of the bad news.

Because this is a phenomenon that is inevitable in this area, as we will see, and its effects have to be mitigated as much as possible.

Year-end anguish

Petrinja, Croatia. Tuesday, December 29.

At 12:19 p.m. the earth is shaking. It is a 4.2 magnitude earthquake. But the worst has yet to come.

The citizens don’t even have the time to realize what is happening (but enough to get out of their homes), that a new quake strikes the city at 12:20 p.m.

The magnitude is 6.4 on the Richter scale. As a comparison, it is similar to the earthquake recorded in 2016 in Central Italy (magnitude 6.5).

Houses, schools and factories fall down like dominos.

The epicenter of the earthquake is 60 kilometers south of Zagreb, in the city of Petrinja (25 thousand inhabitants).

Just the day before, the city has already been hit by a quake of magnitude 5, that caused the first damages.

Twenty-four hours later the mayor of Petrinja, Darinko Dumbović, reports that «half of the city has been destroyed».

In the following days the death toll rises to 7 victims, when the seismographs record three aftershocks - with magnitudes between 3.7 and 4.8 - in the early morning of Wednesday, December 30.

January 2 is declared a day of national mourning.

Again, just a few days ago (January 6), a 5.3 magnitude earthquake hit the destroyed city.

The Croatian prime minister, Andrej Plenković - arrived at the disaster scene with the civil protection and the army - said that 120 million kunas (about 1.5 million euros) will be allocated to support the earthquake victims.

Serbia and the European Union have already announced financial and humanitarian aid programs.

Croatia needs to recover from one of the most powerful earthquakes in its history. We have to go back to 1667, to dig out a worse one: at that time the city of Dubrovnik was also hit by a tsunami.

However, shakings of earth’s surface are not sporadic episodes in this area of the western Balkans. The last years’ events have shown it clearly.

Dramatic years

On December 29, the citizens of Zagreb - close enough to feel distinctly the Petrinja earthquake - experienced moments of anguish that had already lived only a few months earlier.

It was March 22, at 6:24 in the morning. While the nation was in full lockdown for the Coronavirus pandemic - the Croatian capital city was awakened by a violent earthquake.

That was the first warning.

Another shaking, half an hour later. And then, 7 more in the following four days (in an earthquake swarm of 127 shakings), with magnitudes between 3 and 5.5.

Thousands of buildings were damaged, including the Zagreb cathedral: one of the two spires came crashing down, striking the Archbishop’s Palace on its way.

Several dozens of people were wounded and hundreds were evacuated. Nine months later, many of them still don’t know when their homes will be rebuilt. At the moment, they are forced to live in rented apartments, hostels and containers.

The same anguish and uncertainty was recently experienced by Albanians.

We have to turn back the hands of time to November 26, 2019. Just one year before the last quake recorded in the Balkan peninsula.

The Albanian coast, between Durrës, Tirana and Lezhë, was hit by an earthquake of magnitude 6.5. It happened in the middle of the night, at 3:54 a.m., with 16 aftershocks between 4 and 5 on the Richter scale.

This seismic event caused the death of 51 people (other 3 thousands were injured) and enormous damages to the three cities and neighboring towns, as well as to the historical and cultural heritage.

One of the greatest wounds in the recent Albanian history. The responsible wasn’t only nature.

Two months earlier there had already been some warning signals: several slight shakings that alarmed the scientific community.

No emergency evacuation plan was put in place. Some journalistic inquiries have revealed that in the previous years the State resources were redirected or plundered by the corruption in the administrative system.

Money and power - as always in the history of mankind - can do everything.

They even make people forget, when they have to design building policies and urban plannings, that earthquakes on the Adriatic coast are an almost obvious phenomenon.

Everything is linked

Yes, you got it right: in this part of the region, earthquakes are not a predictable phenomenon - because no quake is - but almost inevitable in the medium/long term.

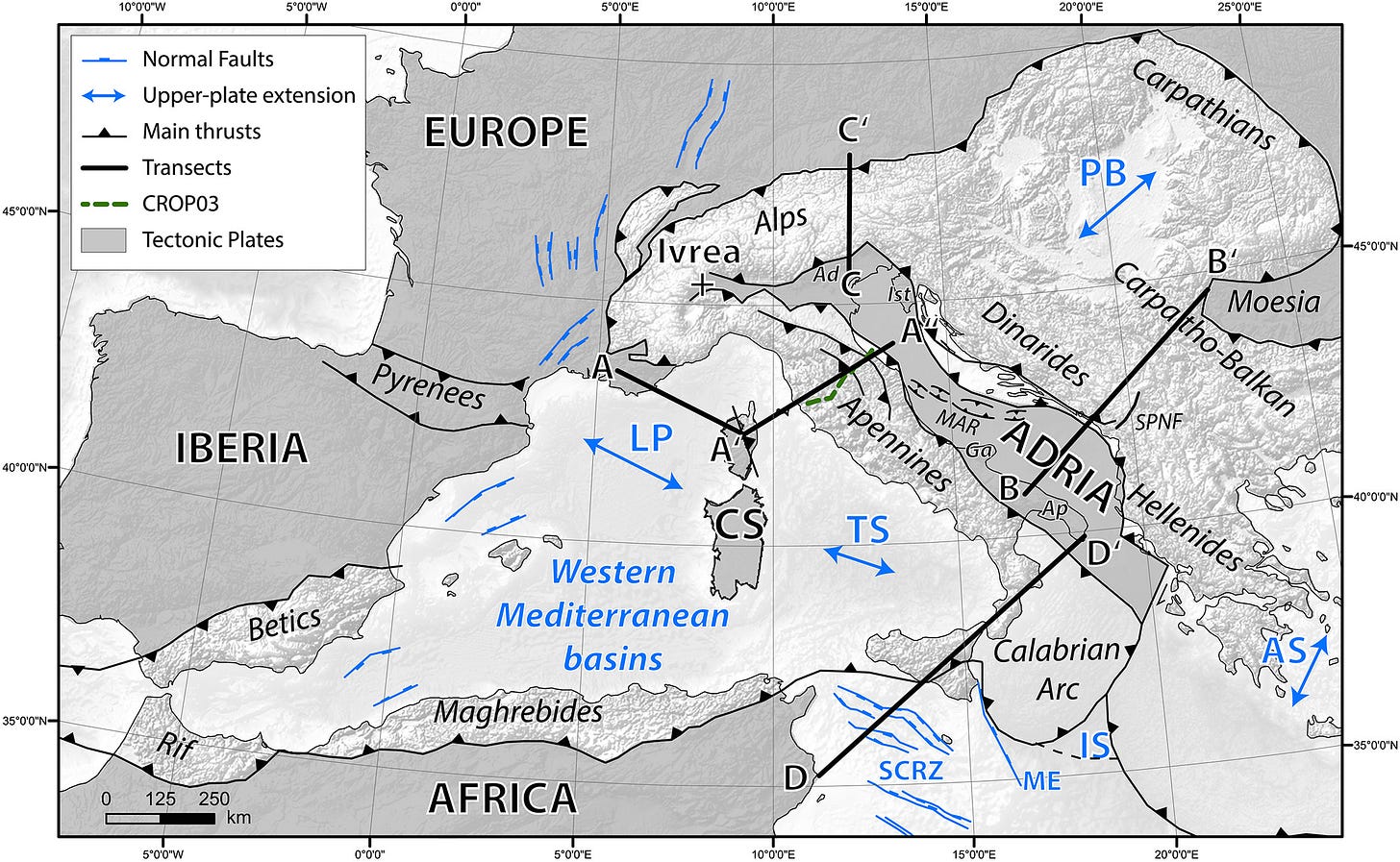

Just look at the map of the lithospheric plates between Europe, Africa and the Mediterranean, and you’ll understand why.

Without having to recall the whole theory of the genesis of a seismic event, we just need to know that an earthquake is caused by the movements of the lithospheric plates, that can come into collision.

The rock masses are subjected to enormous stress, up to the point of fracture. These fractures release energy transmitted as seismic waves, that reach the surface of the earth and propagate.

In the Mediterranean Sea, the Eurasian plate and the African plate come into collision: this is how the Alps and the Apennines in Italy and the mountain chains in the Balkan peninsula were born during the Alpine orogeny.

But in the Mediterranean Sea there are also other several micro-plates - interposed between the two largest plates - which move in a partially independent way.

One of these is the Adriatic micro-plate: from the Ionian Sea it stretches over the entire extension of the Adriatic Sea, up to the Po Valley in Italy.

With a south-west/north-east movement, this micro-plate pushes against the Italian and Balkan Alps, while the southern part rotates counterclockwise, sliding under the Apennine chain.

These different movements are responsible - each in its own way - for the earthquakes in Central Italy in 2012 and 2016, as well as for the quakes in the Balkans during the last year and a half.

As the U.S. Geological Survey (the US government agency that deals with geology and earthquakes) shows, the areas where the most violent shakings from 1900 onwards happened (magnitude higher than 6) are the Aegean Sea, the Anatolian peninsula, the Balkans, the Italian peninsula and the north-west coast of Africa.

The Balkans, indeed.

We cannot be surprised every time the earth shakes here.

It’s time to make prevention again. Through emergency plans, to be implemented quickly in case of need, and building plans that take into account the seismicity of the region.

Any other talk is meaningless.

It will be just another body count.

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road. We need a ray of hope to start again.

What better than sitting down at our bar, the BarBalkans, and letting our trusted host tell us a new story?

We are in Zagreb. Among the buildings that have remained intact, there is one that is somehow... peculiar.

It is the Museum of Hangovers. The first museum dedicated to the most memorable alcoholic nights of people from all over the world.

Traffic signs, plant pots, musical instruments. A collection of the strangest objects found the morning after a boozy night.

Shared stories, zigzag paths “from the bar to home”, glasses that test your reflexes. Interactive experiences that introduce and accompany real life stories.

Rino Duboković, a university student from Zagreb, had this idea in 2019, after a night at the bar with friends telling each other about their most incredible experiences.

The Museum of Hangovers’ history began in that bar.

What is the purpose? «To have a laugh, of course, but at the same time to make people aware of the bad consequences related to alcohol», Duboković told CNN.

Prevention, first of all.

Let’s continue the BarBalkans journey. We’ll meet again in a week, for the 30th stop.

A big hug and have a good journey!

BarBalkans is a free weekly newsletter. Behind these contents there is a lot of work undertaken. If you want to help this project to improve, I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating. As a gift, every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a podcast with an article about the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

If you want a preview, you can listen BarBalkans - Podcast every month on Spreaker and Spotify!

As always, I thank you for getting this far with me. Here you can find all the English newsletters published in 2020.

I invite you to subscribe to BarBalkans with your e-mail address, to receive the newsletter automatically every Saturday morning:

Pay attention! The first time you will receive the newsletter, it may go to spam, or to “Promotions Tab”, if you use Gmail. Just move it to “Inbox” and, on the top of the e-mail, flag the specific option to receive the next ones there.

BarBalkans is on Facebook and Instagram, while on Linktree you can find the updated archive.