S4E16. A 40-year queer struggle

In 1984, Magnus movement organized Yugoslavia's first LGBT Festival in Socialist Slovenia. Researcher Aleksandar Ranković reveals the role and the legacy of these organizations in present-day Balkans

Dear reader,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter with blurred boundaries.

Some struggles have revolutionized an era, a specific political context, and an established way of thinking. However, some of these struggles have been put on hold by unpredictable external events. As if suspended, frozen.

But each time they leave a seed, which would lead even after several years to new struggles in new social and political contexts, revolutionizing the newly established ways of thinking.

This is the case of a little-known issue. The struggle of LGBTQI+ communities in the Balkans over the past 40 years and their common root in the queer movements of the Eighties in socialist Yugoslavia.

A topic that is extremely close and topical, as evidenced by some current references to queer claims for rights and space within a socialist State structure.

BarBalkans will explore this almost forgotten past with the support of Aleksandar Ranković, PhD student at the Department of Contemporary History at the University of Vienna. He will shed light to queer activism between the Eighties and Nineties in Yugoslavia and its legacy in LGBTQI+ struggles in former Yugoslav countries.

Discovering which seeds were left from that 1984 of cultural and social upheaval and what foundations are laid for a more equal and just society. With no discrimination and where everyone can love freely.

How everything started

When can we trace the rise of the queer movements in the region?

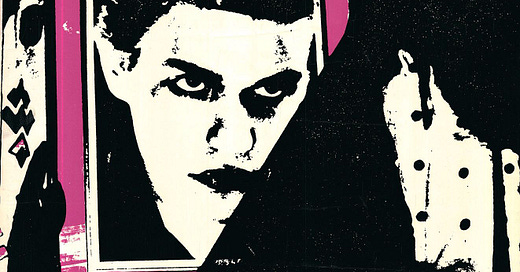

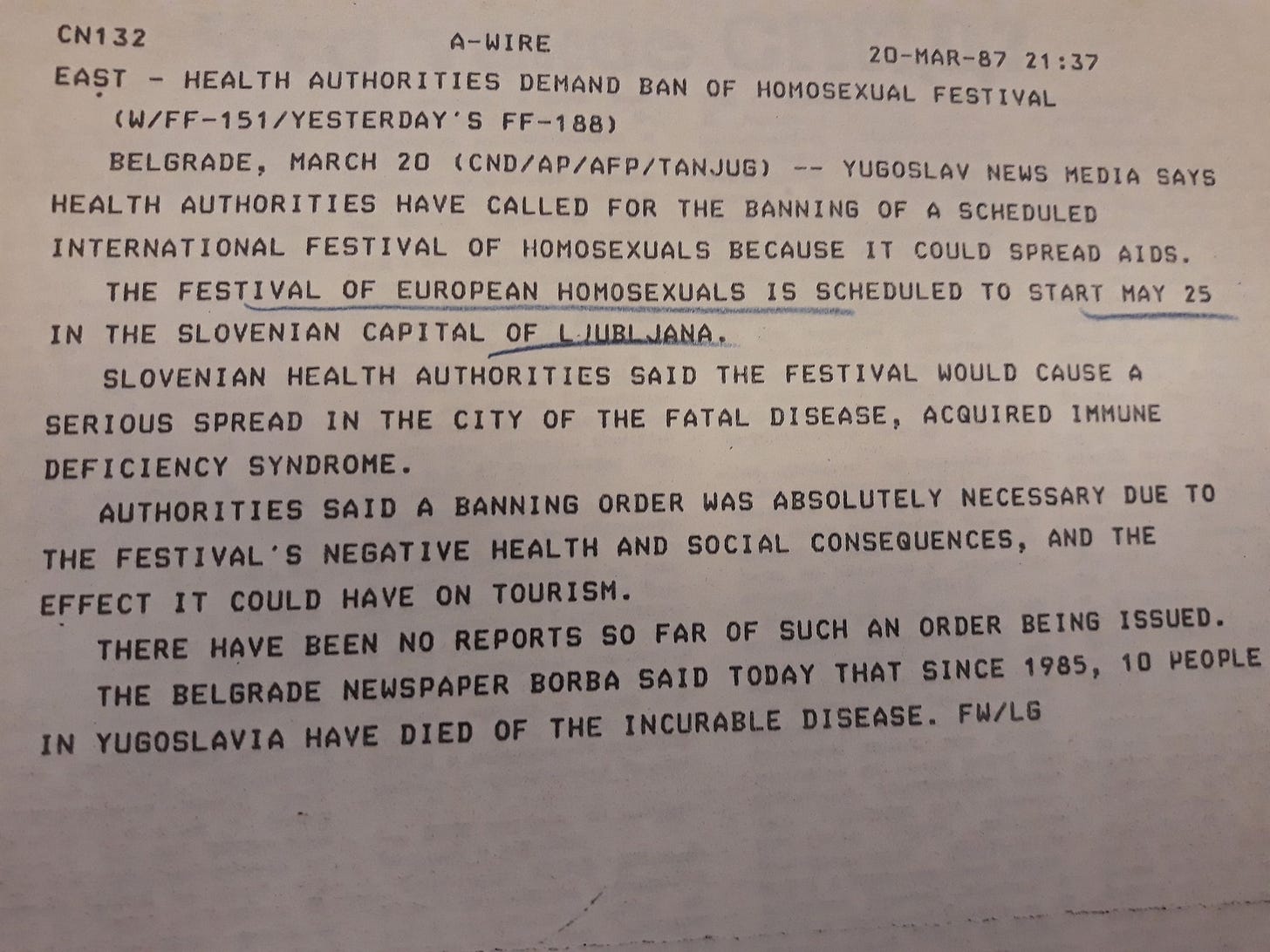

«When we talk about Yugoslavia, the story goes that everything started in 1984, with the emergence of the group Magnus in Ljubljana, in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia. They called themselves “the section for the socialization of homosexuality”.

Magnus was primarily a subcultural/counter-cultural movement, following the classical gay and lesbian liberation movements’ narrative: disrupting normative understandings of sexuality, raising awareness in public, not hiding and conforming.

The first festival - Magnus Festival - was held in April 1984 and it was called ‘Homosexuality and Culture’. This happened in Yugoslavia and was unprecedented, also quite unique across Eastern Europe. Something like this was not possible at all in the Soviet Union or in Romania, for example.

The specifics of Yugoslav socialism allowed LGBT activists to appear in cultural places. This was the beginning of contemporary queer movements in the region».

Read also: S3E9. The legend of fraternal Spomeniks

How was the relation with public authorities in socialist Yugoslavia?

«If we look at this this festival and other cultural activities, Yugoslavia was very liberal. There was clearly a different attitude to censorship, compared to the Soviet Union.

In 1977, homosexuality was decriminalized in the Socialist Republics of Slovenia, Croatia and Montenegro, and in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, while it remained criminalized in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and in the Autonomous Province of Kosovo. However, the attitude also changed there, with reducing persecution.

One of the first issues to be considered is the criminalization and how much male homosexuals - because female homosexuality was not criminalized - were actually persecuted by the State.

Croatian historian Franko Dota wrote the first dissertation on homosexuality in socialist Croatia, showing that roughly around 1,500 people were convicted of homosexuality - called “unnatural fornication” - before it was decriminalized. If we compare this number with other European States at the time, it is relatively low. And if we look at the general framework, the sentences ranged from a few days to six months».

However, it does not seem complete tolerance.

«The story obviously has two sides. Despite Magnus Festival happening every year and it became institutionalized - like a sort of landmark in the Yugoslav discourse on gay and lesbian activism - it does not mean that individual experiences were not quite horrible.

There were “pink lists” in police stations to identify homosexual people quickly. The police’s understanding in everyday life was that homosexual people were more likely to be criminals.

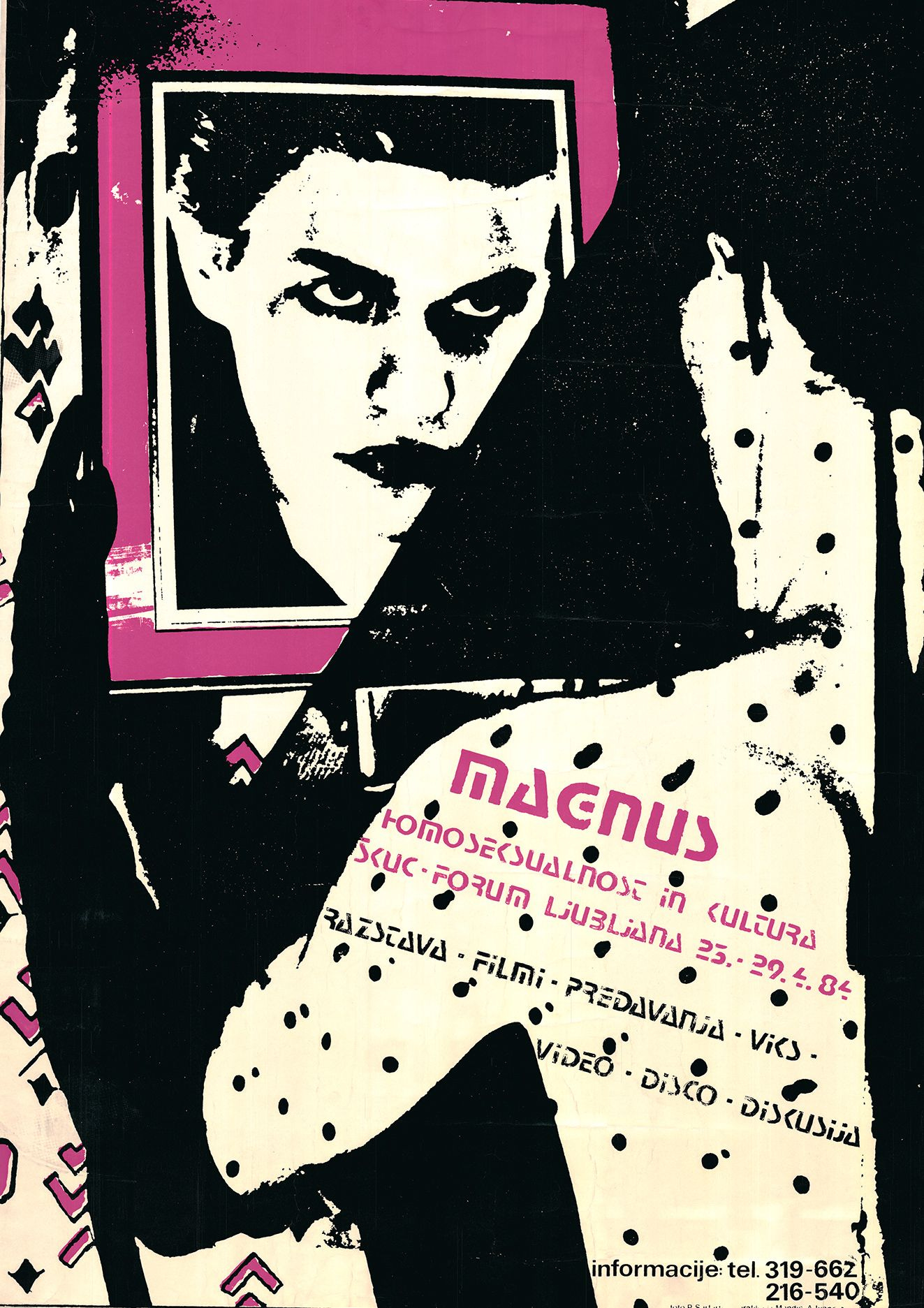

Concerning Magnus Festival, one big incident happened in 1987, when a series of newspaper articles attacked homosexual people because of the AIDS crisis. It was a big factor, which changed attitudes towards homosexuality.

These articles suggested that homosexual people in Ljubljana would organize an international Congress, leading to an uncontrollable spread of HIV across Slovenia and all Yugoslavia, with a negative impact on both tourism and the economy.

It was an absurd argument, but it showed the homophobic attitude that developed once this Festival had become institutionalized».

How do you explain this event?

«The festival was scheduled to be opened on May 25, coinciding both with the International AIDS Candlelight Memorial Day and with Dan Mladosti, one of the major federal public holidays in Yugoslavia.

It was perceived as a provocation by federal authorities. This pressure was mounting and, as a result, Magnus Festival was not organized in 1987. There was only a small exhibition in the Students’ Cultural Center in Ljubljana.

I think this story shows that - in a very homophobic environment - LGBT movements were tolerated and ignored, as long as they organized their activism within certain limits of State authorities, because they did not really challenge federal institutions.

However, they were analyzed by State security services. It has been really difficult to research, because the Slovenian State Security Administration’s archive - much like everywhere else in former Yugoslav countries - was largely destroyed in the Nineties. I do not know if it was an operative surveillance and if there were agents following them, but definitely they were part of the securitization of socialism.

Before 1987, Magnus Festival was more focused on cultural aspects of homosexuality, like education and arts. It was really sex positive. But what happened in 1987 reinvigorated the political aspect of this activism, which had always been present.

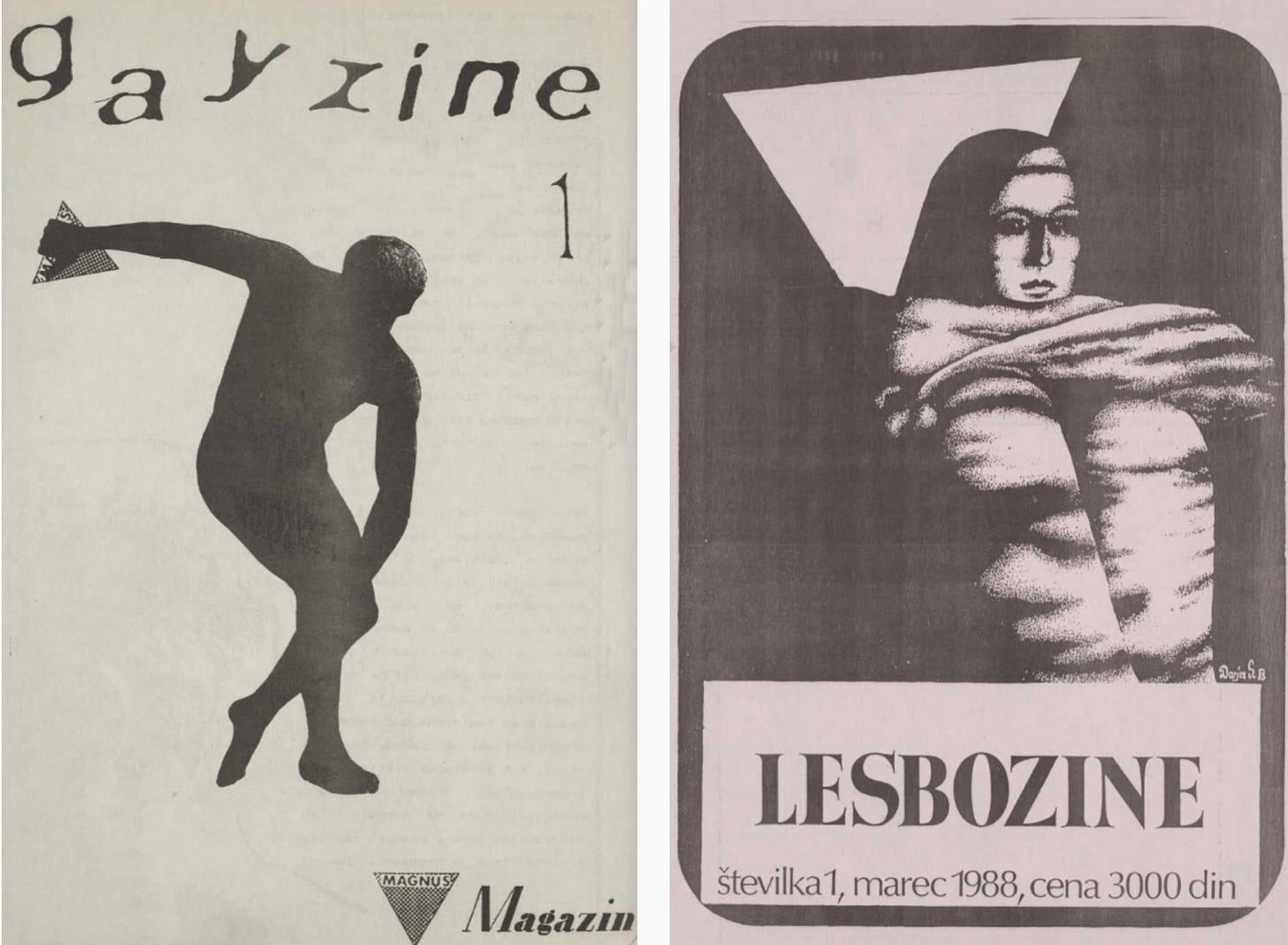

Magnus and the lesbian group LL had joined different activist groups - peace activists ecologist, antimilitary groups - rallying for a more inclusive and democratic society in the Eighties. Even if “democracy” at that time in Yugoslavia meant probably “democratic socialism”.

There was a real interest in a reform of Yugoslav socialism, they were not underground dissidents. They wanted to critically inscribe themselves in this socialist State, institutions and society. For example, these movements wanted a non-discrimination clause in Yugoslav Constitution, to participate and become full members of socialist self-managed society in Yugoslavia. As homosexual people».

From antimilitarism to civil war

What are the main findings of your studies concerning the participation of queer movements in Yugoslav society?

«In my dissertation, I focused on the connections between Magnus and LL and anti-militarism to reform the Yugoslav People’s Army.

In the Eighties, there was a debate about compulsory military service in the Yugoslav People’s Army and civil service as an alternative. Some people were against militarization of society and the classic narratives about the male body.

More interestingly, in the mid-Eighties, the Yugoslav People’s Army conducted a trial period for women lasting two years, with plans for extension. The idea was that women were also to be part of the socialist architecture of defense. When this became public, the question concerned Yugoslav feminism and its varying perspectives on official attitudes towards female emancipation.

On one hand, it would entail greater integration into socialist State structures. But on the other hand, it would be another burden for women, not only within the family and as workers, but also as defenders of socialism. Lesbian women occupied this gap and opposed to the militarization of women in Yugoslav society».

Read also: S4E15. The feminist fight of Serbian Gen Z

What was the impact of the wars in the Nineties?

«In general, the collapse of Yugoslavia precluded this organized activism in Ljubljana, Zagreb and Belgrade from being part of Yugoslav socialism, even if they remained active throughout the Nineties.

There were many radical changes in the way LGBT movements understood the situation, as they were not only activists but also citizens of their respective Republics. They were part of the Yugoslav society and experienced the dissolution and the war from different angles.

At the beginning, there were hopes that something was changing. In the new likely independent Republics - obviously, in 1990 they could not predict the war - these movements would have the possibility to influence the creation of new national Constitutions and secure a place for homosexual people in the new States. There were huge hopes for democracy, anti-discrimination laws and LGBT rights.

When they realized what was actually happening, many of them were disappointed, because the conservative ideas of family and sexuality returned, together with hyper militarization of society and normalization of killings. LGBT people were still excluded.

All the conflicts were also reflected in the groups themselves. At the beginning of the Nineties, the Slovenian gay and lesbian magazine Revolver published some anti-militarist articles in Serbian by an author based in Belgrade. A huge debate inside LGBT movements in Ljubljana emerged, if they should or should not give a space to “the aggressors”, while Slovenia was under attack.

And as the war lasted, the situation became more complicated. There was sort of a hierarchy of needs, especially in Serbia: lesbian and gay people wondered “how much can we speak about homosexual love, when our own country is organizing genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina?”

The radical nature of the events completely shifted the political landscape for these activists. And I think this is also why LGBT activism from the Eighties is not well remembered».

The legacy

Can we still find a legacy of the queer activism during Yugoslav times in today’s LGBTQI+ struggle in the Balkans?

«The legacy depends on where you are. Obviously, the common framework disappeared, and Yugoslavia itself disappeared. I would not say that there is any sort of connection with those times.

But sometimes we can see the Yugoslav flag in Pride events, especially in Zagreb and Belgrade. Zagreb Pride 2006 was called Internacionala [International, ed] and its main symbol was the Red Star.

It may seem like a sense of Yugo-nostalgia among the activists, and this argument is often used to discredit these references in Pride events. But I think that these symbols and these references to the Eighties are actually a way to rethink LGBT rights and queer communities in general».

In which terms?

«The narrative emerged from the 2000s is that the national authorities have to implement the technical framework in the process of joining the EU - they have to introduce the rights - and then, at the end of the process, everyone will be perfectly protected and accepted. But the everyday experience show that, even if there are the rights, the situation for homosexual people as individuals has not changed.

I think the appearance of Yugoslav symbolism in Pride events indicates that queer policies can be more radical, as they are connected to broader social questions of class, political autonomy and more radical global developments.

A way to express that “we do not unquestionably support this liberal consensus on minority rights, because we encompass more than just a minority group and can have an impact on various fields”.

All of this raises a question on what it means to be a queer person in a hyper-authoritarian and proto-fascist society, like in the case of Serbia, where there is a lesbian Prime Minister but zero protection for the LGBTQI+ community.

Police can come to your flat, beat you up and leave, and there will be no political responsibility. At the same time, the Prime Minister does not even comment on the violence, even though she has a partner and a child. This is the total paradox of this democratization model».

Leggi anche: S3E2. Marching for pride

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of the road.

Talking with our host at our bar, the BarBalkans, we really need something to keep the spirits high, before starting again our journey.

«I would be up for Turkish coffee, that is always good for heated political debate», Ranković recommends.

And do not forget that coffee in the Balkans must be drunk slowly. For philosophical and, most of all, practical reason. Trust us!

Read also: S4E13. Gastronationalism tastes like nothing

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 17th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

If you have a proposal for a Balkan-themed article, interview or report, please send it to redazione@barbalcani.eu. External original contributions will be published in the Open Bar section.

The support of readers who every day gives strength to this project - reading and sharing our articles - is also essential to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone.

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support BarBalkans will be able to elaborate new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans - right in that month - 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of The Yugoslav Wars every month on Spreaker and Spotify.

If you no longer want to receive all BarBalkans newsletters (the biweekly one in English and Italian, Open Bar external contributions, the monthly podcast The Yugoslav Wars for subscribers), you can manage your preferences through Account settings.

There is no need to unsubscribe from all the newsletters, if you think you are receiving too many emails from BarBalkans. Just select the products you prefer!

Hmmm... Ranković likely has good intentions, but he shifts the narrative to a socialismolatriac field where his ideologised past is exclusively socialism/communist party rule focused. Also, he knows little of the events related to LG (then just LG, later LGB, and later yet LGBTQ) liberation in the 1980s and early 1990s I took part in.