XXXIV. This is not just a (video)game

Military operations and ethnic cleansing of the Yugoslav Wars are virtually resurrected. Gamification encourages not only Serbian revanchism, but also the European far-right movements

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the Italian newsletter whose aim is to give a voice to the Western Balkans’ stories, on the 30th anniversary of the Yugoslav Wars.

Today we will talk about video games.

Do you think this sounds a little childish or nerdish? I will try to change your mind.

First thing: we will deal with war games, which probably everyone has tried at least once in their life.

But above all, video games that simulate the Yugoslav Wars are not like the others. In this case, the war is of course fought through a console, but historical revisionism and nationalist revanchism jump out of the screen.

From the Balkans, all this can reach you.

But in the real world.

How to refight a war

«Cover me when I run over, drop the bomb!»

Sound of an explosion and bursts of machine guns.

We are in the middle of a conversation between a group of gamers, immersed in the virtual reimagining of Operation Storm, in August 1995. In the video game, they have to prevent the Croats from regaining control of the Republic of Serbian Krajina.

Gamers assume the role of Serbian rebels, engaged in a counter-offensive that never happened. Almost 26 years ago, the Croatian army operation ended with hundreds of civilian deaths and about 200 thousands Serbs forced to flee their homes. The largest exodus of a Serb population during the Yugoslav Wars.

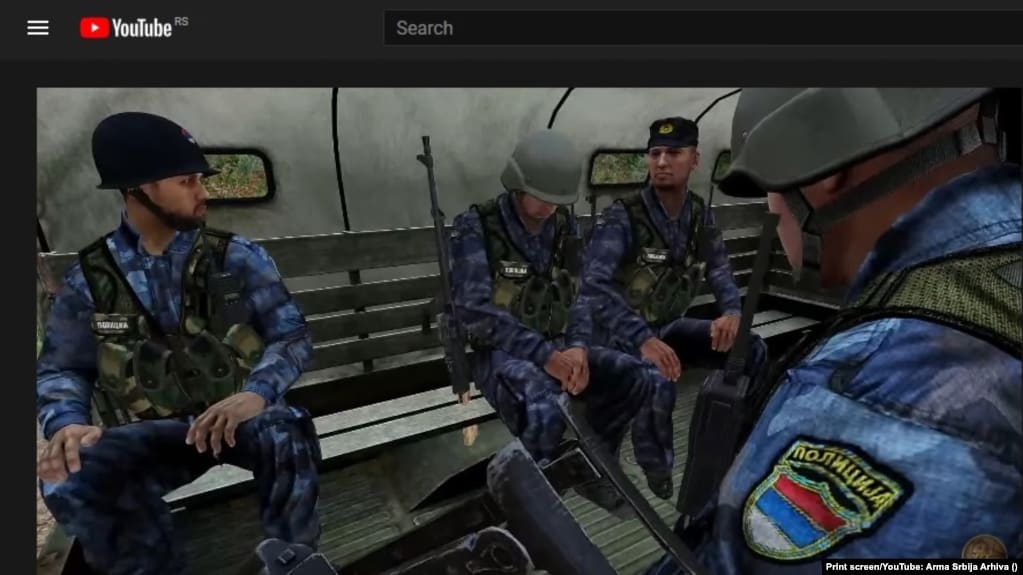

This is one of the war scenarios of Arma Srbija, the most popular online gaming platform in Serbia. We are talking about a first-person shooter, a video game genre centered on a weapon-based combat in a first-person perspective.

Have you ever heard of Call of Duty? This is the same, but the setting is in the Ten Years’ War in the former Yugoslavia.

Gamers publish their recordings on YouTube and share their games with more than 2,600 subscribers.

Most of the time, Arma Srbija’s missions take place where war crimes have been committed. And gamers always fight against Croats, Bosnians or Albanians. Never ever against Serbs.

Another mission, Operation Jashari, simulates the siege of Donji Prekaz village by the Serbian military forces in March 1998. Adem Jashari, one of the commanders of the Kosovo Liberation Army (UCK), was killed along with more than 50 members of his family. Only a 10-year-old niece survived.

«Our task is to liquidate Adem Jashari», reads the description of the video on YouTube, which has almost 159 thousand views.

And then, there is Operation Racak, with over 71 thousand views. This is about “reviving” the massacre of 45 ethnic Albanian civilians by Serbian-led security forces in the Kosovar village of Racak.

The event was one of the factors that led to the NATO bombing campaign in 1999. Obviously, in the video game it is not described as a massacre.

Arma Srbija

Arma Srbija is a spin-off of Arma, a series of tactical military games produced by Bohemia Interactive. The platform allows to simulate missions of armies around the world, from Libya to Afghanistan.

Concerning the military operations in former Yugoslavia, the official game Arma 3 has undergone many changes. These modifications are in jargon called “mod”.

Basically, gamers can do that on their own - from small details to new radical elements - and the mod are incorporated into the original game.

They can create their own scenarios, add content, clothes, weapons, vehicles and structures. They can also change basic components and start new gaming experiences.

The mods are shared on the platform Steam Workshop: since the release of Arma 3 in 2013, over 75 thousand mods have been shared. Producers may risk loosing control of their product modifications:

«We are not specifically aware that there are mods based on conflicts in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, but we would also not be surprised if they exist».

This statement by Korneel van’t Land, Bohemia International spokesman, perfectly explains how easy it is to lose track of people responsible for the original game’s modifications (and even to wash their hands of those).

As the popularity of such mods increases, more and more propaganda and nationalistic elements are incorporated into the video game, rewriting history.

Bohemia Interactive spokesman adds:

«Controversial story settings are usually created by users who feel the desire to know more about certain historical events. If this is really the motivation, then video games can play an important role in how we look at past conflicts, integrating books, films and other media».

But at the same time,

«If someone creates a mod with the idea of spreading hatred or inciting violence, then we consider it very worrying».

This is what normally happens.

The Arma Srbija platform offers users “great joint games with Russian, Greek, and other white communities”, providing “a unique experience of virtual warfare, side by side with Serbian soldiers”.

One of the main developers of Arma 3 mods concerning the Yugoslav Wars is Red Hammer Studios. The official website states that the purpose of Arma Srbija is to give “a realistic representation of the Serbian armed forces”.

In order to become a member of the Arma Srbija platform, a gamer has to fill out a membership form. Then, he can download his favorite mods, join the forum and take the online training. At this stage, he can join a team, after the authorization of an admin.

Arma Srbija is the most popular first-person shooter about the conflicts in former Yugoslavia. But in Serbia there are also other minor video games, that imagine new - never existed - scenarios to fight non-Serbs.

Conflict 2012: Kosovo Sunrise (2009) sets military operations in the future (in 2012). The Albanian guerrillas in Kosovo attacked the international military forces and the player, as the commander of the Serbian forces, must resolve the conflict.

Return to Kosovo and Metochia is a mod of the video game Operation Flashpoint. The mission takes place in winter: Americans have realized they were wrong in Kosovo and now they support Serbs to win back towns and villages.

All this among Serbian patriotic songs, virtually reproduced by the loudspeakers and car radios of military trucks.

Gamifying extremism

Now, you may be wondering what this has to do with you and your life.

If we just talk about Arma Srbija, probably not much. But the extremism of some comments may raise a red flag.

For example, commenting on Operation Jashari, user Magg0t92 writes: “If you need information, I know everything, because my father’s unit led the operation”. User Aleksandar Janjić gives a feedback on Operation Racak: “Nice mod, but it was better in real life in 1999”.

Silence and denial of war crimes in the 1990s are part of political and cultural life in Serbia. It is not really surprising that video games show the same phenomenon.

But there is a problem. If young gamers do not receive a proper education on historical events, how can they distinguish in video games what really happened and what did not?

The risk of historical revisionism and revanchism is already real.

It is time to leave the Balkans.

Linda Schlegel, a PhD student and researcher on online radicalization at Goethe University in Frankfurt, in an article for European Eye On Radicalization writes that more than 2.5 billion people all over the world play war games.

Even if the effects vary from person to person, «there is the possibility that constant exposure to these contents may normalize the perception of violence», explains Schlegel.

In this context, many extremist organizations have developed new games or modified and adapted existing ones to their own needs.

For example, in 2015 one of the Arma mods simulated war scenarios in Syria and Iraq, where an Isis fighter had the aim of killing as many Western people as possible.

The mod was developed by Daesh supporters and it was used to radicalize vulnerable individuals and to recruit young fighters across Europe.

But gamification directly affects also the spread of white, xenophobic and racist extremism in Europe and its connections with online propaganda.

It became clear with the terrorist attack on the synagogue in Halle (Germany) on October 9, 2019.

Stephan Balliet live-streamed the assault with a camera on his arm, in the style of a first-person shooter video game.

CNN has defined it the “gamification of terror”. Jacob Davey, researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, noted that «even people criticizing the attacker shows how these attacks have become gamified: their criticism was that his ‘score’ wasn’t high enough».

This perception has an impact on video games. German far-right network Ein Prozent (under surveillance by Berlin intelligence) created the free-to-play video game Heimat Defender: Rebellion.

As reported by Vice, gamers can choose to play as one of the many figures of the far-right scene in Germany.

The aim is to save the country - killing all the anti-fascists - and to face the supreme enemies: the chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel, and the Hungarian-American philanthropist, George Soros.

If extremism that infiltrates through video games in the Balkans seems far from your reality, you should consider that something similar is happening in Germany.

A EU country, often seen as a virtuous social model.

And now, do you still think that video games are a little childish or nerdish?

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

The link between gamers and energy drinks is well known, for many reasons that you can easily explore here.

This is why today on our bar - the BarBalkans - we find an energy drink that comes from Serbia.

It is Guarana, produced by Knjaz Miloš in the city of Aranđelovac.

Guarana is made from extracts of the guarana plant, that has one of the highest concentrations of caffeine in the vegetable world. In relation to its weight, guarana can contain from 3.6 to 5.8% of caffeine. The coffee plant does not exceed 2%.

This is why Guarana is famous for having the higher caffeine content than almost all other energy drinks on the market.

It will be even more difficult now to sleep a wink.

Let’s continue the BarBalkans journey. We’ll meet again in a week, for the 35th stop.

A big hug and have a good journey!

BarBalkans is a free weekly newsletter. Behind these contents there is a lot of work undertaken. If you want to help this project to improve, I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating. As a gift, every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a podcast with an article about the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

If you want a preview, just listen to the last episode of BarBalkans - Podcast published on Wednesday: you can find it on Spreaker and Spotify!

As always, I thank you for getting this far with me. Here you can find all the newsletters.

If you want to help me to make this experience grow, you can invite whoever you want to subscribe to the newsletter:

Pay attention! The first time you will receive the newsletter, it may go to spam, or to “Promotions Tab”, if you use Gmail. Just move it to “Inbox” and, on the top of the e-mail, flag the specific option to receive the next ones there.

BarBalkans is on Facebook and Instagram, while on Linktree you can find the updated archive.