XLVI. Kuala Lumpur, Bosnia

9,000 kilometers away from Sarajevo, during the War a community of Bosniaks found refuge in the Malaysian capital city. A relationship strengthened by work, faith and the fight against COVID-19

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the Italian newsletter whose aim is to give a voice to the Western Balkans’ stories, on the 30th anniversary of the Yugoslav Wars.

It is 11 a.m. on a classic rainy day. But it is very hot.

Some Bosnians meet in a bar downtown and they discuss the issue of the COVID-19 in the country, over a coffee.

Serbia is achieving great results, while Sarajevo has just started the vaccination campaign. The pandemic is scary and the number of cases is rising.

Calmly, they finish their Bosnian coffee, they say goodbye and return to their homes.

In Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia.

Why is a group of Bosnians living more than 9 thousand kilometers away from “home”, rooted for decades in a Southeast Asian city?

And why are they discussing the Malaysian government’s decision to help Bosnia and Herzegovina with tens of thousands of doses of the COVID-19 vaccine?

Behind a veil of tragedy and rebirth, there is an extraordinary hidden story.

(Not) so close to homeland

Before the beginning of the Nineties - when our story actually starts - there was a small but tight-knit community of Bosnians in Malaysia.

They were technicians and engineers sent by the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s companies to work in Malaysian branches, such as the energy giant Energoinvest.

After Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union’s rupture, Marshal Josip “Tito" Broz kick-started the Non-Aligned Movement and tried to use its connections for the economic development of the Federation.

Southeast Asian doors were opened to Yugoslav State-owned enterprises, from Indonesia in the Sixties to Malaysia in the Seventies.

For Bosnians, there was not only an economic incentive, but also a religious factor to consider.

In Malaysia, Islam was and still is the State religion: it was an hospitable habitat for Bosniaks, the Slavic ethnic group of Islamic faith. To be precise, both Bosniaks and the majority of Malaysians believe in Sunni Islam.

This is why the opening of economic relations between the two countries also stimulated a cultural exchange between Sarajevo and Kuala Lumpur.

The Bosnian community in Malaysia was enriched with students and professors at the International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), thanks to many scholarships in Economics, Islamic Sciences and Social Sciences.

The goal was to integrate these disciplines. Double degrees and courses offered in English and Arabic then broadened the academic offer.

A few months before the start of the Yugoslav Wars, Kuala Lumpur was a second homeland for dozens of Bosniaks.

Few months later, the ethnic cleansing carried out by the Serbian President, Slobodan Milošević, forced hundreds of other Bosnian Muslims to find refuge in that new home, on the other side of the world.

Community of refugees

Between 1992 and 1995, the visa-free departure point for Malaysia - via Croatia - was an option considered by many Bosniak families.

They found a government ready to welcome them, a great defender of the persecuted Europeans’ rights.

In particular, the Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad. He totally embraced the Bosnian cause, taking tough positions during the War.

He recalled everything in his autobiography, where he vehemently dwelt on the «great upset» caused by the genocide in Bosnia:

«What the Serbs did was unimaginably cruel, but what the Europeans did was equally appalling and their inconsistency was shameful. If a dog gets stuck in a drain, they spend time and money to rescue it. Yet they refused to help innocent people who were being killed».

The Bosnian refugees who managed to reach Kuala Lumpur were hosted in the southern district of Serdang. Another group, in the nearby Kajang area. A third group settled in the Malaysian State of Sarawak, on the island of Borneo.

Especially in the capital city, Bosnian Muslims began to rebuild their community, with all its social and cultural characteristics: Serdang became the center of cultural events and of Bosniak religious holidays in Malaysia.

The children attended Malaysian schools, integrating into the new society. At the same time, they kept alive the memory of the Bosnian language, history and culture, thanks to a school opened within the community.

In May 1994, the Malaysian daily New Straits Times featured on its front page Bosniaks gathered in Serdang to celebrate the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha.

But the newspaper kept often an eye open on the events in Sarajevo, in those tragic years.

When the war in Bosnia ended in 1995, the majority of the Bosniak diaspora’s members decided to go back home.

Despite the Malaysian hospitality, the distance from homeland, the tropical climate and the very different culture played an important role in their choice.

In the late Nineties and early 2000s, only a small group of Bosnian Muslims remained in Kuala Lumpur.

However, the experience of the Bosniak community was not only a sui generis war diaspora, but also a case of reverse brain drain, with a multiplier effect on the home country.

In those years, the number of students at the International Islamic University Malaysia had increased. They were the protagonists of the return migration.

The international exposure and the cultural diversity of Southeastern Asia shaped their worldview, while the familiarity with technologies made those young people professionally specialized.

Young, educated and proficient in English, in Bosnia they quickly found an employment in international companies and organizations, and they had an impact on post-war society.

Something that was made possible by the Bosniak diaspora in Malaysia. And the red thread connects even the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

An indissoluble bond

In the Western Balkans - and especially in Bosnia - the vaccination campaign is proceeding slowly.

[If you need a good insight, I recommend you the 41st episode, “The vaccine battle for Middle-earth”]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Bosnia and Herzegovina has registered 200,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 out of 3.7 million inhabitants. The mortality rate is 4.3%, with 8,762 deaths.

The difficulties of the European “partner-country” convinced Malaysia to intervene.

In comparison, the country has registered 428,000 confirmed cases, but out of 32 million inhabitants. With 1,610 deaths, the death rate is less than 0.4%.

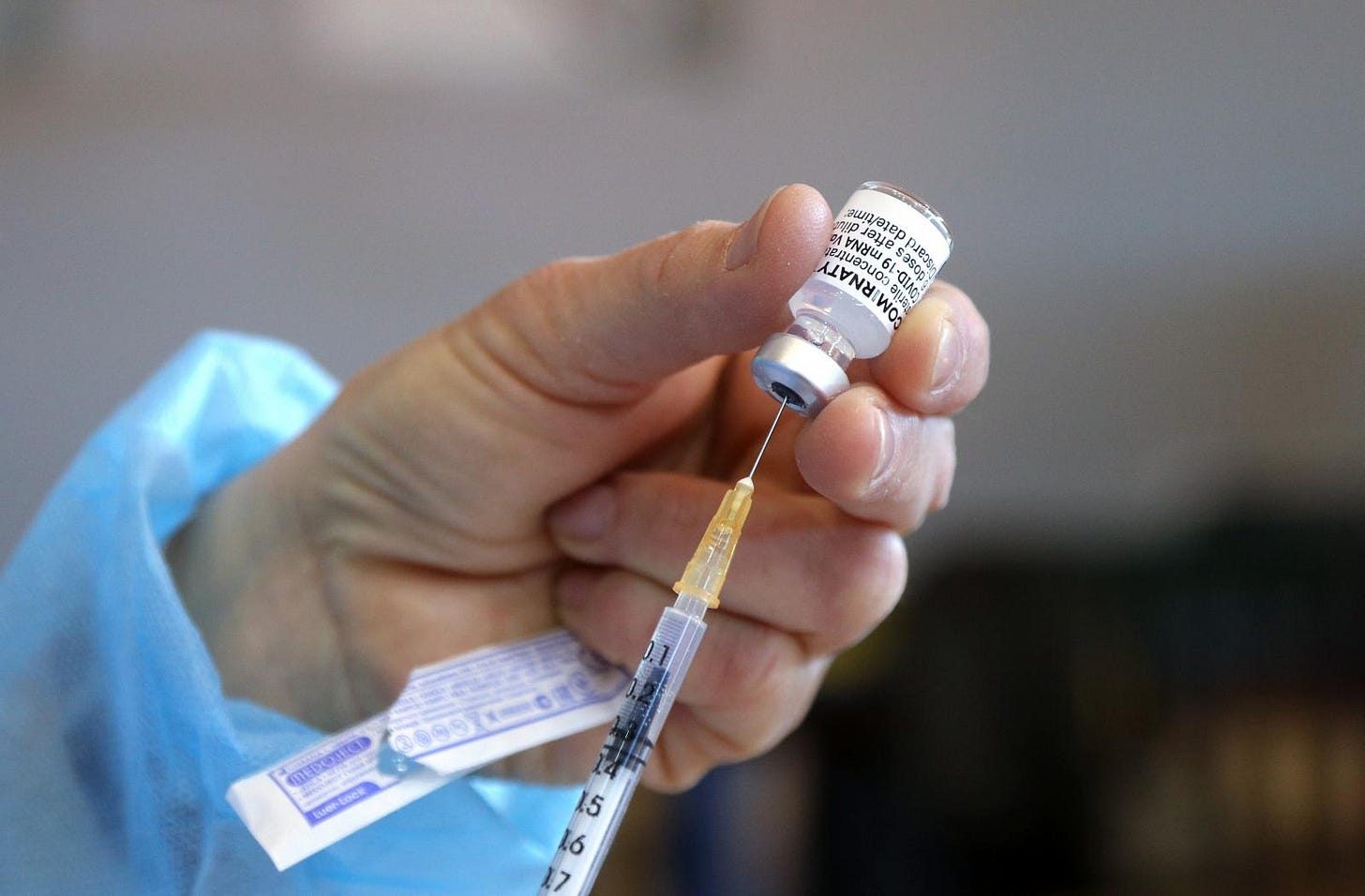

Given these data, in early April the government in Kuala Lumpur agreed to send 50 thousand doses of COVID-19 vaccine to Sarajevo.

The Minister for Special Functions, Mohd Redzuan bin Md Yusof, explained that the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina asked for support «to address the increase in infections and the difficulties of the European community».

The Malaysian government has not yet decided which type of vaccine will be delivered, as it needs to consider the logistical capability of Bosnia and Herzegovina first.

The agreement must be as simple as possible, to ensure that the support will not be a burden or go wasted.

Both the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Health will take over the delivery: «We understand that not all countries are as lucky as Malaysia», the Minister added. «From what we have received, we have set aside the amount for them».

Decades of close relations between the two countries made Malaysian intervention natural in a time of difficulty for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

There is a little bit of Bosnia in Kuala Lumpur.

There is a little bit of Malaysia in Bosnia.

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

Like the transplanted Bosnian community in Malaysia, today the experience at our bar, the BarBalkans, is a bit different.

Let’s discover teh tarik, the Malaysian national drink.

Introduced to the Malaysian peninsula by Indian Muslim immigrants, the drink is made of black tea mixed with hot condensed milk.

The word teh tarik is composed of two terms from two different languages: teh means “tea” in the Hokkien dialect, while tarik means “pulled” in Malay. The name comes from the process of preparation.

The mixture of black tea and condensed hot milk is poured back and forth repeatedly between two vessels from a height, giving it a thick frothy top.

Furthermore, this process cools the drink down and improves the flavor.

Traditionally teh tarik was brought to workers in Malaysian rubber plantation. Since then, it is common to associate this drink with a great energy source.

Even the Bosnian community in Kuala Lumpur has absorbed this custom and the group still living there is used to alternate teh tarik with traditional Bosnian coffee.

But also many families who have returned to Bosnia still prepare this drink today, in memory of the experience in their second homeland, 9 thousand kilometers away.

Let’s continue the BarBalkans journey. We’ll meet again in a week, for the 47th stop.

A big hug and have a good journey!

BarBalkans is a free weekly newsletter. Behind these contents there is a lot of work undertaken. If you want to help this project to improve, I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating. As a gift, every second Wednesday of the monthyou will receive a podcast with an article about the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

If you want a preview, just listen to BarBalkans - Podcast. You can find it on Spreaker and Spotify! Don’t miss the next episode on Wednesday!

As always, I thank you for getting this far with me. If you are interested in the Bosnian society, I recommend you these previous newsletters (while here you can find all the others):

If you want to help me to make this experience grow, you can invite whoever you want to subscribe to the newsletter:

Pay attention! The first time you will receive the newsletter, it may go to spam, or to “Promotions Tab”, if you use Gmail. Just move it to “Inbox” and, on the top of the e-mail, flag the specific option to receive the next ones there.

BarBalkans is on Facebook and Instagram, while on Linktree you can find the updated archive.