It is June 1992.

The siege of Sarajevo has caused the first massacres, such as the one in Markale market [you can listen to the latest episode of BarBalkans - Podcast here].

International public opinion has begun to understand what is happening in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the atrocities committed by the Army of Republika Srpska.

In response to Belgrade’s support, the United Nations imposed sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Belgrade, which is banned from the international community.

However, as the war continues, the Western powers are divided, exacerbating a conflict that is now out of control.

Ferments in Belgrade

The Western harsh economic sanctions seriously shake the power of the Serbian President, Slobodan Milošević.

Milošević himself calls the UN Resolution 757 as «ridiculous» (he is long prepared for this eventuality), but part of the public opinion reacts with anger.

Opposition parties - which united into the Democratic Movement of Serbia (DEPOS) on May 24 - demand Milošević’ resignation and organize a protest rally on June 4, gathering thousands of people in Belgrade.

Students, professors, artists and intellectuals join in. But the real problem, as already seen in March 1991 protests, is that anti-Milošević arguments do not have a hold on the masses.

The regime’s propaganda presenting the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (although it would be fair to say Serbia) as the victim of a global conspiracy and the Serbian President as the man of destiny is much more appealing.

Moreover, opposition parties show a general inability to play their role, as often happened in history.

In early June, the results of May 31 Yugoslavian parliamentary elections are published: the elections that DEPOS decided to boycott.

This is how, in Serbia, Milošević’ Socialist Party reaches 50 percent of valid votes, while 35 percent goes to Vojislav Šešelj’s Radical Party.

The Parliament in Belgrade is in the hands of nationalists, more or less radical. As a consequence, most of moderate and educated society begins to leave the Serbian capital. Young students, especially.

After the danger has passed, Milošević begins to strengthen the regime, ensuring that the special police forces have more personal, more weapons and more equipment.

In the meantime, he acts on the leadership of the Federation.

On June 15, he works to have Parliament elect Dobrica Ćosić as the first President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. He is a puppet of the Serbian President, but he is extremely popular.

As a Serb has been elected to the presidency of the Federation, the Constitution would provide for a Montenegrin to assume the leadership of the Federal Council.

On the contrary, Milošević offers on a silver platter the role of federal Prime Minister to billionaire Milan Panić. He is a former cycling champion, who escaped Yugoslavia in 1955 and got rich in California with the pharmaceutical company ICN.

The U.S. President, George H. W. Bush, guarantees a temporary lifting of the air block on Serbia to let him come back home.

Without batting an eyelid, Milošević welcomes Panić in Belgrade as President of Serbia and the real leader of all Yugoslavia.

The Western world divided over Bosnia

What really emerges in June is Milošević’ ability to circumvent all the restrictive measures put in place by the Western world, thanks to the warehouses full of foodstuffs and the reserves of energy and raw materials.

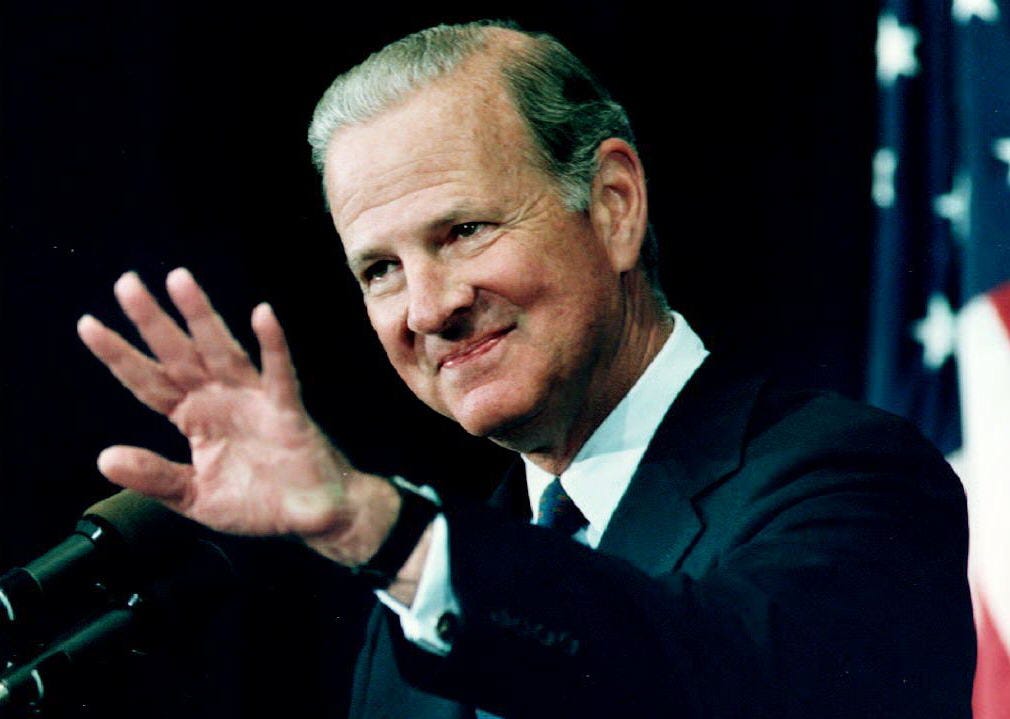

This is why - as the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the siege of Sarajevo continue - the U.S. Secretary of State, James Baker, considers the extreme solution.

A direct military intervention by the Western powers.

Following some discussions at the White House - that show the impracticality of this option - a working group headed by Baker works on the memorandum Game Plan - New Steps in Connection with Bosnia.

The document is aimed to secure humanitarian aid to Sarajevo, including four actions:

Sending an aircraft carrier to the Adriatic;

Strengthening sanctions, with a block of the Montenegrin port of Bar;

Stopping oil supplies from Romania to Serbia;

Conducting multilateral airstrikes against artillery in the mountains of Sarajevo.

Although President Bush is in favor, Game Plan is scuttled by the opposition in the U.S. military circles to a direct intervention with an international coalition, like the one formed during the Gulf War.

On the ground, UNPROFOR (the United Nations Protection Force) returns to Sarajevo, after its headquarters were moved to Belgrade in May.

On June 8, the mandate is redrafted by Resolution 758, sending 60 military observers and 1100 Blue Helmets. Three days later, the unit commanded by General Lewis MacKenzie reopens Sarajevo Airport.

However, this event does not prevent neither increased bombardment of the city nor the siege of the Muslim enclave of Bihać (in North-Western Bosnia).

The consequence is twofold.

On June 20, Bosnian President, Alija Izetbegović, declares the state of war and general mobilization.

And then, the European Community leaders react harshly, approving a resolution proposed by German Foreign Minister, Klaus Kinkel. The text specifies that «while peaceful means are the priority, the use of military resources is not excluded», in case Serbs and Serbs of Bosnia prevent the flow of humanitarian aid.

This reaction seems to foreshadow unity among the 12 Member States.

Instead, it is undermined by the behavior of the French President, François Mitterrand.

On June 28, Mitterrand flies to Sarajevo without consulting partners. He wants to corroborate the French view of Bosnian conflict: a civil war is taking place, not a military aggression. Therefore, there is no space for external intervention, except for humanitarian aid.

The mission is planned in detail, to the extent that Serbs proclaim a unilateral cease-fire on the eve of his arrival.

Although Mitterrand arrives to symbolically open the airlift to Sarajevo - and Sarajevans welcome him in celebration - his trip is characterized by the controversial relationship between Paris and Belgrade.

The day chosen coincides with the Battle of Kosovo Polje in 1389 against Ottoman troops, celebrated by Serbs as the mythological foundation of their nation (and the reason why Kosovo would unquestionably belong to Serbia).

Moreover, according to several French politicians and military officials, the presence of Islam in Bosnia represents an element of destabilization for all Europe. They are not able to consider the historical and cultural roots, but they see it only as a projection of the Arab world.

And finally, an important role is played by the lens of French centralist tradition, which labels Slovenes, Croats, and Bosniaks as separatists and Ratko Mladić’ troops as authoritative only because of their regular uniforms (compared to the informality of the Bosnian army).

All this prejudice and presumptions lie in Mitterrand’s mission to Sarajevo. But there is also a good dose of malice in preventing, with his physical presence, international military action against Radovan Karadžić’ Republika Srpska.

Obeying UN Resolution 761, Serbs of Bosnia troops relinquish control of Sarajevo Airport to UN Blue Helmets on June 29. Only apparently proving that external military intervention is unjustified.

This is the beginning of the big illusion of the airlift over the Bosnian capital.

The war fronts

Operation Provide Promise in Sarajevo will become the longest-running airlift in history, with 12,951 flights, more than 160 thousand tons of food and nearly 16 thousand tons of medicine conveyed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

However, despite the announcements and grand opening by the French President, it will initially prove to be a fiasco.

Not only because the security in the corridor between the airport and the city is very low, even if French, Egyptian, and Ukrainian Blue Helmets are in charge of it (but no one thinks about the railroad between the Adriatic Sea and Sarajevo).

But also because only 20 percent of the food sent every day reaches the population. Part of the responsibility lies with the Army of Republika Srpska, another part with the head of the Bosnian army, Šefer Halilović, who organizes an illegal network to resell food at a high price, starving Sarajevans.

In the meantime, the situation on the ground in the rest of the Republic is complicated by the attitude of the Croatian President, Franjo Tuđman, who is put under pressure by the international public opinion after the Conference in Graz.

In order to defend himself against allegations of trying to establish Greater Croatia (true), Tuđman orders the withdrawal of three brigades from Posavina, along the Sava River. However, his troops would have the possibility to inflict losses on the Army of Republika Srpska.

This decision allows Serb forces in Banja Luka and Bijeljina to rejoin and create an ethnically compact corridor in the controlled territories in Northern and Eastern Bosnia on June 28.

Territories lost in Posavina are counterbalanced by the advance of Croat-Muslim forces in Dalmatian hinterland.

On June 17, the city of Mostar is liberated from the siege started six weeks before and a large portion of territory on the left bank of the Neretva River is occupied.

This will be one of the last joint operations of Croats of Bosnia and Bosniaks, whose relationship has long been undermined.

Everything is now enough to open a new front of war.

If you liked this article, you can spread this parallel journey and the free weekly newsletter:

If you know someone who can be interested in this newsletter, why not give them a gift subscription?

Here is the archive of BarBalkans - Podcast:

And here the summary of 1991.

Share this post