S5E16. The shadow of lithium looms over Bosnia

Residents of the Majevica mountain massif oppose a new mine project in the heart of the natural park. As in Serbia, economic and geopolitical interests are closely intertwined

Dear reader,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter with blurred boundaries.

A new threat to both the environment and democracy is unfolding in the Balkans.

At stake is a park renowned for its breathtaking landscapes and untouched wilderness—its future now hanging in the balance.

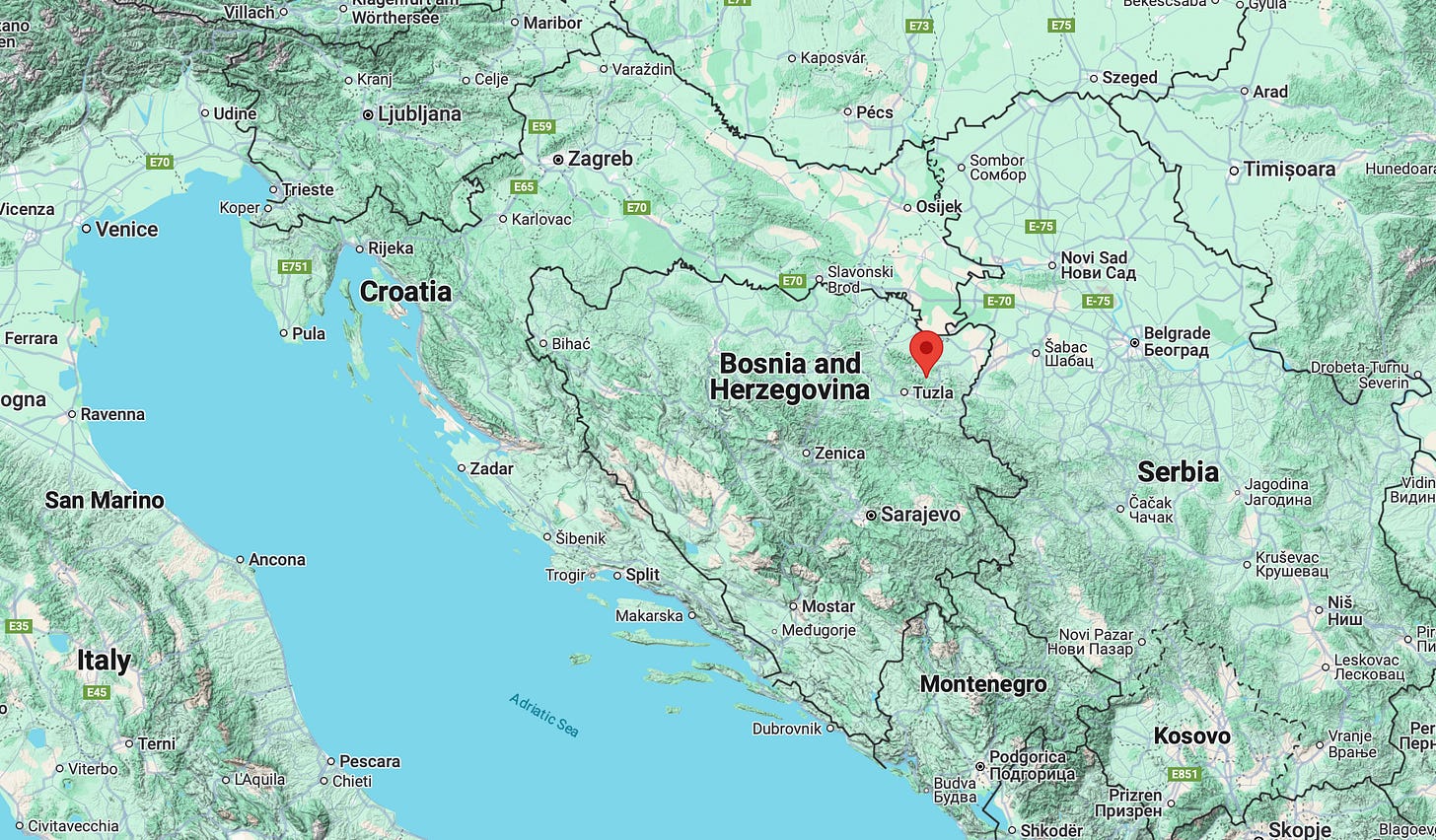

For months, the Majevica mountain massif in Bosnia and Herzegovina has been in the spotlight—not for its potential inclusion in the EU’s Natura 2000 network of protected sites, but for a far more contentious reason.

The discovery of a lithium deposit in Lopare, deep within the park, has triggered a race to exploit one of the most coveted resources of the century.

Once again, economic interests threaten to override the voices of local communities, fueling environmental destruction and disregarding grassroots opposition in pursuit of political and geostrategic gains.

BarBalkans is a newsletter powered by The New Union Post. Your support is essential to ensure the entire editorial project continues producing original content while remaining free and accessible to everyone.

A familiar story

It was March 2024 when the Swiss company Arcore AG published the results of its geological and mining research in the Lopare area, about fifteen kilometres from Tuzla, in the northeast of Republika Srpska (the Serb entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina).

The deposit is estimated to contain 1.5 million tonnes of lithium carbonate, 94 million tonnes of magnesium sulphate, and 17 million tonnes of boron.

The planned lithium mine is located within the Majevica mountain massif, an area currently undergoing assessment for potential designation as a Natura 2000 protected site.

Majevica’s natural park has emerged as a thriving tourist destination, drawing both hikers and travellers eager to explore a region still largely undiscovered for its historical and cultural richness.

The deposit could mark a turning point for the Tuzla region and Republika Srpska as a whole. Its president, Milorad Dodik—who is engaged in an unconstitutional bid for secession from Sarajevo—has hailed the deposit as “an opportunity for development not to be missed.”

Read also: XXXII. Tomorrow’s oil

However, the ecological consequences could be severe. Majevica lies near the watershed of the Gnjica River, a tributary of the Sava (which ultimately feeds into the Danube), and the Janja River, which flows into the Drina.

Beyond the vast amounts of water required for lithium extraction, the risk of groundwater pollution threatens to contaminate the region’s main waterways.

This looming threat has sparked local resistance. Residents are rallying against plans to exploit the deposit, launching a petition to block the approval of extraction concessions.

It’s a story the Balkans know all too well.

In Serbia’s Jadar Valley, the local community has been fighting since 2004 to stop multinational mining giant Rio Tinto from opening a lithium mine.

This environmental and social struggle is spreading like wildfire across Serbia, becoming part of a broader movement against corruption in the regime of President Aleksandar Vučić.

And with it, the true scale of the economic and geopolitical interests tied to lithium mining is coming to light.

It's still a European issue

After Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina is now drawing the attention of multinational mining companies due to its lithium deposits. According to research by Arcore AG, the Lopare mine could remain operational for up to 65 years.

Demand for lithium is rising steadily and is expected to grow for the foreseeable future, as it is a crucial raw material for batteries—not only in smartphones but also in electric vehicles.

In short, lithium will be central to the transition towards a low-carbon economy.

This is why international players are racing to secure as much of it as possible—including the European Union, which urgently needs this critical mineral for the green transition of its automotive sector.

Brussels reinforced this urgency with the EU-Serbia Memorandum of Understanding on the strategic partnership on sustainable raw materials, battery value chains and electric vehicles, signed in Belgrade in July 2024.

An agreement that is already exposing the EU’s vulnerability to pressure from authoritarian leaders, as economic interests take precedence over the rule of law—the very foundation of the EU project.

“If this is true—if fundamental democratic principles are being compromised for short-term economic gain—it would be a short-sighted and neocolonialist approach,” warns Slovenian MEP Vladimir Prebilič (Greens/EFA) in an interview with BarBalkans. “Striking deals with autocrats simply to secure access to raw materials should never be the EU’s strategy.”

Instead, “any form of assistance or cooperation must be rooted in our fundamental democratic values,” Prebilič insists, stressing that “while democracies are not perfect, they are far superior to autocratic regimes.”

According to the Slovenian MEP, “if we want to remain honest with our partners, we must encourage them to uphold democratic principles”—particularly in the Balkans, where “any political deterioration would have direct consequences” for the rest of the continent. “Ignoring this would be extremely unwise.”

This is why, Prebilič makes clear, the European Parliament “will never support” the exploitation of resources “if it goes against the will of the people and democratic principles,” whether in Serbia or Bosnia and Herzegovina.

What the EU institution can do, he adds, is “raise public awareness, support those fighting for their rights and national well-being, and ensure that candidate countries stay on a path aligned with European values.”

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of the road.

Today, at our bar, BarBalkans, we remain in the heart of a Bosnian natural park, exploring the vineyards that flourish on the slopes of the Majevica mountain.

The ancient Celts called this land Lubnichi (Ljubniča), meaning ‘fruitful’. Austro-Hungarian maps from the 19th century attest to the fertility of this area, which supplied the Empire with high-quality grape varieties for premium wines.

Following the world wars of the 20th century, the tradition of viticulture was almost lost. That was until 2013, when Pajić Winery was founded in the village of Bukvik, with the first 1.5 hectares of vineyards planted with Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot, and Chardonnay.

The Pajić family is dedicated to restoring this heritage, a commitment reflected in their wine labels. The design features an old map unearthed in the archives of the Vienna land register, a testament to Bukvik’s winemaking legacy.

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 17th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

Behind every original product comes an investment of time, energy and dedication. With your support The New Union Post will be able to elaborate new ideas, articles, and interviews, including within BarBalkans newsletter.

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of The Yugoslav Wars every month on Spreaker.

Discover Pomegranates, the newsletter on Armenia and Georgia’s European path powered by The New Union Post

If you no longer want to receive all BarBalkans newsletters, you can manage your preferences through Account settings. There is no need to unsubscribe from all the newsletters, just choose the products you prefer!