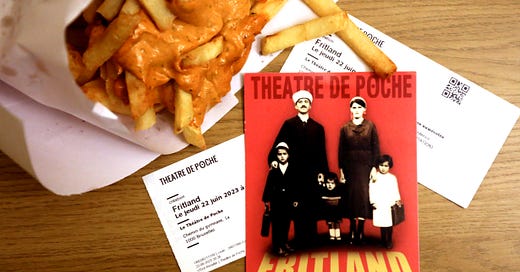

S4E6. 'Fritland'. Belgian fries in Albanian sauce

Interview with Zenel Laci, author of the play named after Brussels' most famous fries shop and produced by Théâtre de Poche. Story of a migrant family, of personal redemption, patriarchy and freedom

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter (and website) with blurred boundaries.

A red-and-white tent, the sizzle of potatoes thrown into boiling oil, the smell of fried food that envelops anyone who approaches an unforgettable sign: Fritland. The land of frites, Belgium’s famous fries.

If Belgium is the kingdom of frites, Brussels reigns as the undisputed master. But that red-and-white tent in the heart of the Belgian capital hides a unique story.

To the people of Brussels, Fritland is the ultimate fries shop. However, the most Belgian of all the Belgian businesses was founded 35 years ago - and it is still run - by a non-Belgian family.

The story of Fritland begins in Albania. With a voluntary escape and exile, with the dream of a father to reach the United States. With the arrival in Belgium and a fries shop. With the work of an entire family, children included.

And it’s the courage of a son who finally finds the strength to say ‘no’ after years of living within a rigid patriarchal structure, starting a new life of his own. Out of Fritland, finally in Belgium.

And now Fritland is no longer just a fries shop. It is a play staged in Brussels. Fritland, by and with Zenel Laci.

That son who left his ‘Albania in Belgium’ to find himself. And today, after the success of his play at Théâtre de Poche, tells BarBalkans the story about his family and Fritland.

His story.

Albania in Brussels

How was it possible for an Albanian family to start one of the most typically Belgian businesses in Belgium?

«In 1952, my grandfather left Albania. He was a royalist and a member of King Ahmet Zog’s army, he wanted to continue to defend democracy. But one day he was warned that the communists were ready to arrest him. He had only one day to prepare and leave with his family.

He just wanted to save himself. Instead, my father - who was 16 years old - wanted to go to the United States. He stayed in Kosovo some time and got married. After eight years in a refugee camp in Croatia, they needed to travel from Yugoslavia to Italy before heading to the United States. But in 1962 my family was refused the US visa.

At that time Belgium offered free education for children, housing and jobs. So my family moved there in 1963. My parents and grandparents were born in Albania, my older sisters in Kosovo, my older brother in Italy, me and my other brother in Belgium. This is the story of our journey!

However, my father always had that dream of the United States, even when he was in Belgium. By chance, a Portuguese in Brussels offered to leave him his fries shop: if he wanted to make easy money, that was the best business. Potatoes are cheap, but what is expensive is the labor. So he told us: “Everyone at work, no matter the age”.

It was 1978. My father noticed a place called Pizzaland, the land of pizza. Therefore, he thought: “We make fries, our store has to be called Fritland!”

I had to drop out of school and started peeling potatoes for many hours a day. In those days it was something very common, because we had to get out of poverty. I started working at the counter of the shop when I was 16.

The business began to be successful. It was an incredible opportunity for people who had recently discovered what frites were. And it is still there, run by the family».

How did your family’s relationship with Albania develop in Brussels?

«From the time we were in exile, we had no contact with Albania for 40 years. If you cannot go back to your country, everything is mythicized: that was the most beautiful country in the world, everything was magnificent. This is what we are fed, without any real image. And we don’t ask questions.

For example, in elementary school the teachers did not understand my nationality: Albanian? Italian? Where is Albania? Next to Greece there is only Yugoslavia, right? Albania had withdrawn from all the Treaties, it did not exist anymore, it did not have a name.

Besides, I came from a family where we did not read. One day, a client overheard us and he told me about Ismail Kadare and The General of the Dead Army. It was someone from outside the family who made me discover that Albanian writers existed, that we were not just mechanics or bus drivers».

There was a lot of traditionalism in your family, while the professional activity is all ‘Belgian’. Isn’t it a contradiction?

«It was indeed a contradiction. But this was the reality: inside the house is Albania, outside is Belgium. And even if the fries shop ‘is Belgian’, in any case it was Albania. The structure of the people was Albanian, only the products were Belgian.

My father used to say: “You are Albanian, you stay Albanian”. But this is not possible. It was the contradiction between my father, who was the guardian of Albania through this fries shop, and all the people passing by from morning to night, who were free. It took me a while to figure it out: the shop was just a way to make money as fast as possible, to get us to the United States.

We can say that at that time we were not even in Brussels. Fritland was the only place known to be run only by Albanians. My father used to tell us to feed any Albanian who had no money, because for sure they had suffered. And whatever was left over at the end of the night was given to the homeless people in the city center.

Our shop had become a place of well being for many people. Even for Albanian ambassadors - when the country reopened to the world - who were paid in lek and could not afford to live in Brussels. This is how I had the opportunity to meet many Albanian intellectuals».

Inside and outside of the fries shop

How was your integration in Brussels, as the son of Albanian migrants?

«I was born in 1966. When I was in elementary school, Belgium was not prepared to accept us. Belgians accepted the generation of the parents, who were the brawn, but they had not thought about the fact that we had a brain. There was a gap for the generation of children like me in the Seventies.

I remember very well that in the classroom they put Belgian children in the front and everyone else in the back: Turks, Portuguese, Greeks, Hungarians, Albanians. The teachers communicated with Belgians, while they were extremely violent with us.

One day, a teacher slapped me in the face because I stuttered while reciting a poem. Another child was beaten by four teachers, because he had falsified a grade. We were a generation that no one tolerated in school».

Instead, what did Fritland represent to you while growing up?

«As the youngest son, it was hell for me. Until the Nineties no one in Brussels wanted to live downtown. It was extremely violent, we had to fight to save the cash register and the shop.

Especially for me - rather shy, introverted, dreamy, interested in books and nothing else - but I had no choice. It took me a long time to realize that I did not belong there.

No one could say ‘no’ to my father, because Albania, our history and even he himself were mythicized. I think this applies to all the families who experienced exile, who suffered, who saw deaths on the run. Who were we - born in Belgium, with a job, heating, water to wash ourselves - to say ‘no’?

I was the first one who said '“no, I can’t be loyal anymore”. Because it was really a matter of loyalty: the only way to save myself was to leave. I won my freedom at the age of 30, ‘abandoning my family’ but defending my siblings. Just because your father suffered, this does not mean you have to suffer as well».

What was the most difficult moment in Fritland?

«The football match Juventus-Liverpool in 1985. The Heysel Stadium, the city and the police were not ready for hooligans.

On the day of the tragedy, I was alone at work. There had been riots the night before, but only a few more than usual. However, the next day thousands of hooligans arrived and all hell broke loose.

At the shop, we did not have enough food for all those people, who were trying to steal everything. I had to stab, otherwise I would die. I was 18 years old, I went out of my mind to serve them and, at the same time, to defend the shop. They were savages, it was traumatic.

When the tragedy happened, the police decided to close the entire downtown. But my father told us: “Never in the world, there is no law that forces us to close”. Fritland was the only business open: the Albanians defending a piece of Belgian territory, because they thought the police were not able to do it».

And what was the best moment?

«There are two moments. A homeless man had seen me reading in the fries shop, and one day he arrived with two books: The Eye and the Spirit by Merleau-Ponty and Existentialism is a Humanism by Sartre. Joseph was a retired French teacher, affected by a personal tragedy.

We became friends and he helped me explore literature, existentialism, humanism and various literary trends. He read my first text and gave me confidence in myself.

The second moment happened a short time before that episode. At the shop, there were a lot of papers for wrapping chips in paper cones, so I used them to write short poems on customers’ stories. But I would not show them to anyone.

One day, I took the paper with the poem The Bottle at Sea, I put the fries inside and I gave them to a customer. An hour later, he came back: he was eating the chips, when he noticed the sheets and read the poem. He said: “It is wonderful, I just came back to tell you that you have to continue!”»

The curtain opens

What happened after the farewell to Fritland?

«When I left, I did not know what to do with my life for three years. I wanted to attend university and take courses in French literature: I wanted to become a French teacher. But my father had not let me go to high school.

I enrolled at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, but there was too much difference with the young students. They had a freedom that I did not understand. Ironically, I met a group of young communists: me myself, coming from a family escaped the communist regime.

However, I found that the progressive ideals were very good. In fact, I remained a leftist, the only one in the family, even though I never had a party card! Those young people let me discuss politics, the concept of progress and socialism. It had nothing to do with what I had heard about the dictatorship in Albania.

But still, I needed to go to school. The Information Service for Studies and Professions directed me toward the only course that included literature: scenography.

I enrolled in that course, I was 30 years old and already had a child. I worked like crazy and I made it. I had a diploma, but I actually fell in love with theater. So I started writing and staging».

And why did you finally decide to talk about Fritland specifically?

«So many people over the years had asked me why I did not write the family history. I did not feel up to it: I was the youngest, I had heard a lot about it but had not experienced it. But it stayed in a corner of my mind.

Then, I wanted to write about my years at the fries shop, letting Brussels speak through the customers I had seen in 18 years of work, day and night. The Stock Exchange district and the rest of downtown were not like today.

I was thinking of a show on the people I met and I had identified myself as a character, become the pretext to talk about all the customers. This is how I started writing and staging it in 2017 with actor Thiebault Vanden Steen.

Thiebault advised me to talk with the director of the Théâtre de Poche. He read the script and told me that he had already seen many plays about customers in a store, in a bistro or in a restaurant. But he also stressed that “you have a pearl, but you do not realize it. The pearl is you”.

He proposed me to write the play of my life at Fritland and promised me that he would produce it at Théâtre de Poche on one condition: that I would be the one to perform it. Even though I was not an actor.

This is when I started talking about my family, the story of Fritland. And especially about a young man of Albanian origin, who had dreams and who was in his place in the world. That fries shop, which was both an inspiration and a prison».

What does this play mean to you?

«I was 52 years old when I made it. I wanted to share the Albanian hospitality: at the end of the show, we serve fries like when I was a child, as a tribute to my father. Because all has been forgiven. I continue to tell the story with honest and sincere communication.

And when I peel the potatoes during the show, it is like I am talking to my father, to my grandfather and to Albania. It makes me comfortable on stage. But it was difficult for me to become an actor and to tell this story.

The first time we rehearsed, I realized I was not good at it. Denis Laujol, who is on stage with me, thought of a way to help me if I had difficulties. But then I improved with time and we decided that we needed a dramaturgy.

At the beginning of the play, Denis acts as a lion tamer with me. But what is really intriguing is that I am the one who emancipates himself as the show goes on».

‘Fritland’ was also performed in Albanian and in Kosovo. How did it happen?

«I got to know the director of the Balkan Trafik Festival, Nicolas Wieërs, thanks to one of my plays about an Albanian activist and author of Diary of a Kosovo Woman, Sevdije Ahmeti.

Every year, Nicolas chooses a Balkan capital to launch the Balkan Trafik Festival and the press campaign. In 2023 it was in Kosovo and he invited me there to represent the play. It was a great opportunity to perform in Kosovo.

Then, the director of Théâtre de Poche, who was involved in the project, told me: “You can do it in Albanian here too!” The play was produced in both languages, allowing Albanians who just arrived in Brussels and had no knowledge of French to have access to a play in a theatre».

How did your family react to this play?

«Since I left Fritland, I had not seen family for three years. I needed to rebuild my life, to understand what Belgium and Brussels meant to me. After bottoming, I got back up. I had to form new connections, as I had a rejection of Albanian culture.

In 2017, as my brother heard that I was going to make a show about the family and Albania, he was convinced that I wanted to be offensive and mean. On the other hand, I was certain that it would be cathartic.

The director gave us two years to create, recreate and stage the show. In 2019, at the premiere, the whole family was there: my father and sister had died, but my mother, brothers and the Albanian community were there. It is very rare for a renowned theater to host a play about Albania or Albanianness.

At the end of the play, everyone cried. A very patriarchal, archaic, proud community had never undergone introspection. And it was really cathartic. My mother said: “I saw and I heard it all, bravo!” And also my brother admitted: “All right, I got it”».

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

Today our bar, the BarBalkans, meets Fritland in a very special way, thanks to Zenel Laci:

«The show has been a great success. Denis and I fry the fries for everyone at the end of every show. One day, the director asked me: “Why isn’t there an Albanian sauce for the fries?” I thought he was joking. But the following year, he repeated: “Where’s the Albanian sauce?”

Well, we did it and it has been very appreciated, even if tested by chance. So, we have patented the ‘Albanian sauce’ and we are going to start selling it at Fritland, to see if it works!»

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 7th stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

If you have a proposal for a Balkan-themed article, interview or report, please send it to redazione@barbalcani.eu. External original contributions will be published every last Friday of the month in BarBalkans - Open bar section.

Your support is essential to realize all that you have read. And to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone.

An independent project like this cannot survive without the support of the readers. For this reason I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating:

Every second Wednesday of the month you will receive a monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening in the Balkans - right in that month - 30 years ago.

You can listen to the preview of BarBalkans - Podcast on Spreaker and Spotify.