S4E1. Anilda Ibrahimi. Overcoming limits

BarBalkans is back on the road with the fourth season of this newsletter. And with an exclusive interview with the Albanian writer deeply rooted in Italy, author of novels that combine these two souls

Hi,

welcome back to BarBalkans, the newsletter (and website) with blurred boundaries.

Like every year, when summer is almost over, it is time for us to get back on the road. Before we start the new season, I steal just a few seconds from our guest.

BarBalkans’ fourth year starts with the promise to open this newsletter to external original contributions on everything that concerns the Balkan region. Politics, culture, society, sports, art, film, cuisine, spirituality...

For this reason, BarBalkans newsletter will host articles, reports and interviews by collaborators once a month. They will be published every last Friday of the month and you will receive them directly in your inbox.

These contributions will be transparently paid - it is always sad to point this out, but the general editorial landscape is rather bleak - and they will respect some well-defined BarBalkans’ guidelines.

If you are interested in pitching an article proposal or if you want to learn more about this project, just write to redazione@barbalcani.eu

I thank you for your trust. We will meet on the last Friday of September with the first contribution of BarBalkans - Open bar.

And now we can start with our journey.

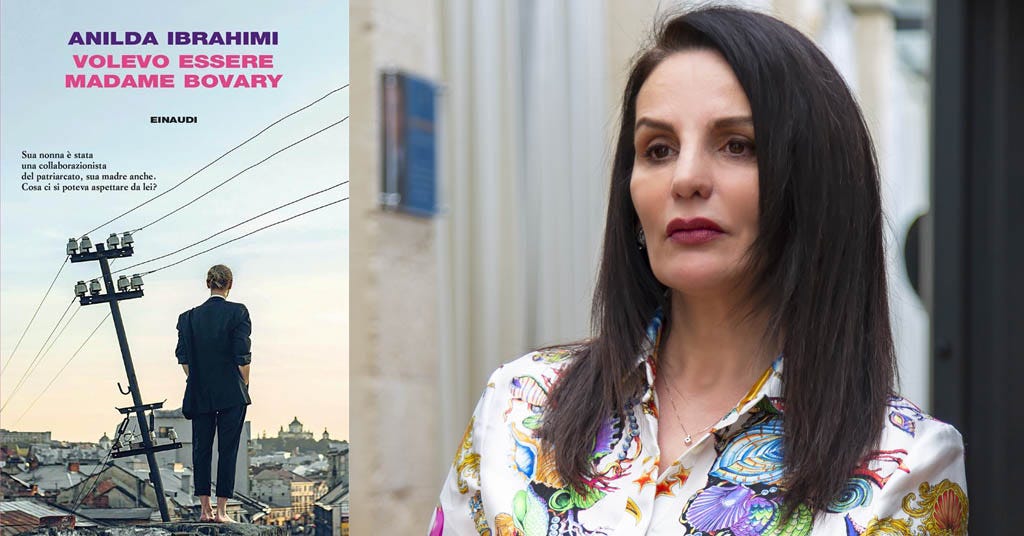

BarBalkans’ fourth season starts together with Anilda Ibrahimi, Albanian writer deeply rooted in Italy and author of Italian novels focused on the history, culture and society of Albania over the last century.

And - perhaps this is no less important - winner of the first edition of the Balkan Playoff, BarBalkans’ half-serious summer contest on Instagram with the most well-known Balkan people.

Ahead of the times

Born in Vlorë, Ibrahimi graduated in Modern Literature at the University of Tirana. In 1994 she moved to Switzerland and then in 1997 to Rome, where she worked as a consultant for the Italian Council for Refugees until 2003.

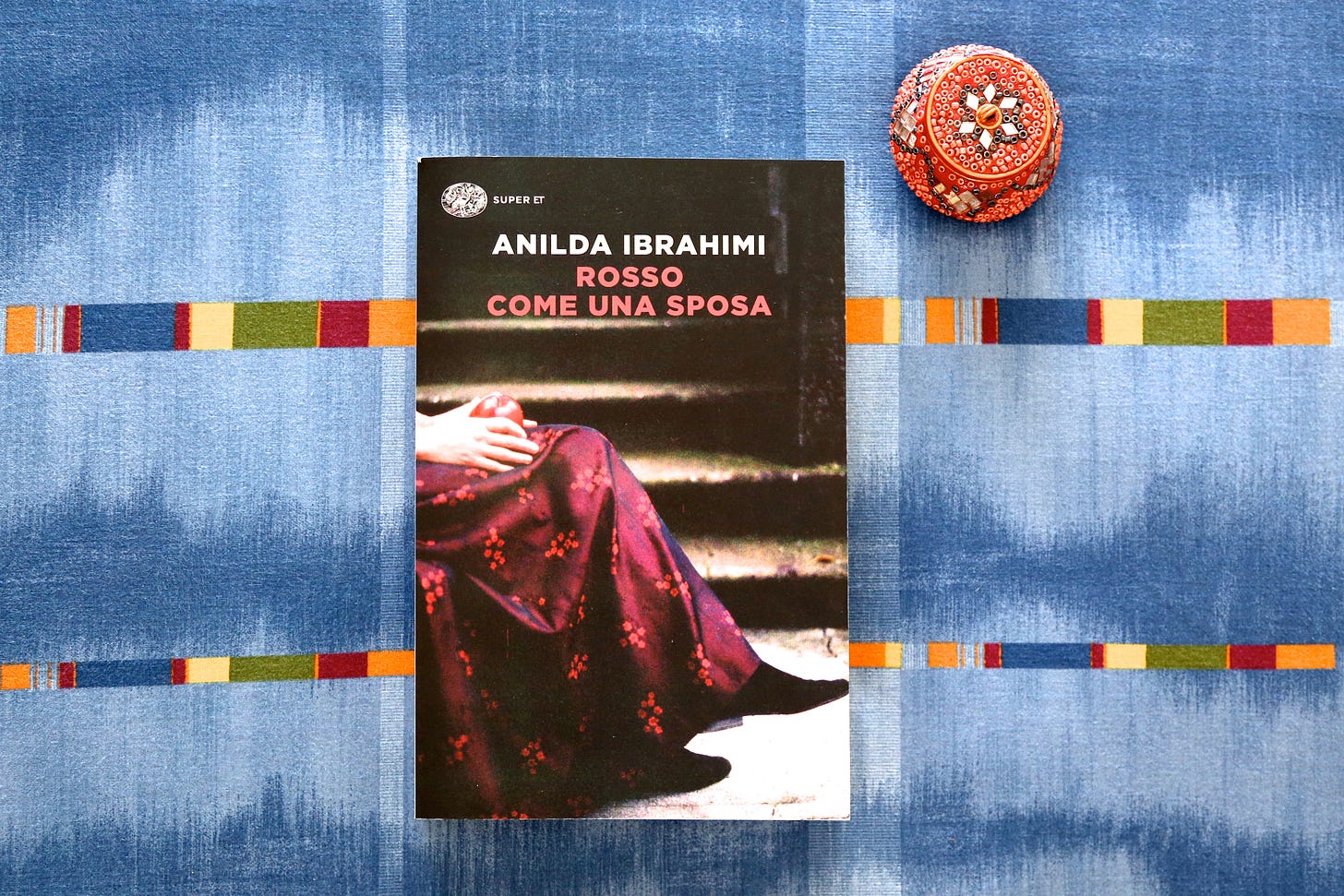

She is journalist and writer. Her debut novel Rosso come una sposa was written in Italian and published in 2008. It is focused on the vicissitudes of the women of a family through the social changes of Albanian history: from the archaic world of the early 20th century to Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and the post-communist society.

She published L’amore e gli stracci del tempo in 2009 - the film rights have already been optioned - Non c’è dolcezza in 2012 and Il tuo nome è una promessa, winner of Rapallo Prize in 2017. Her latest novel, Volevo essere Madame Bovary, was published in 2022.

All of Ibrahimi’s novels are translated into six languages and highlight the strength of Albanian women against the backdrop of historical events in Albania and the Balkans.

What are your sources of inspiration when you devise a new story for a novel?

«I am not one of those writers who suddenly have an epiphany. I think for a long time about the story I want to tell, perhaps this is the phase that lasts the longest for me. I have always been ahead of the times with the stories I have told so far.

In the first novel Rosso come una sposa I told a generational story of matriarchy, where women are not described as victims. Of course, they suffered and had to carry all the weight of life on their shoulders, but they also were resilient and, above all, had a unique strength. They showed a strong female solidarity - an overused word nowadays - that was real, as a reaction to a male-dominated society. They understood that the only way to cope with patriarchy was to unite among themselves.

In L’amore e gli stracci del tempo I wrote about ethnic rape, that is sexual violence against women to strike at the honor of men. “Filling their bellies”, affecting the ethnic composition of a territory. Women were just mere containers of male seed, and this was all part of a plan put in place by men.

In Non c’è dolcezza I told the story of motherhood in all its forms. A woman decides to give birth to a child for her friend who cannot have babies, the equivalent of the modern-day surrogacy.

In Il tuo nome è una promessa I wrote about reception: a Jewish family that is welcomed in Albania during the Holocaust and saved along with almost three thousand refugees.

And the last one, Volevo essere Madame Bovary, about the impact on women’s life of the absence of sentimental education.

Personal history certainly plays a role, but it is not everything. I appreciate collective stories, with issues that matter to us as a community».

History and life stories

How do life stories of ordinary people help the narration of a broader and less known historical context?

«When I write a novel, small stories interest me the most. Ordinary people living their lives, until something happens overwhelming their destiny. My characters find themselves in the middle of History, even if they did not choose it.

Zlatan and Ajkuna in L’amore e gli stralci del tempo are two of them. So is Abigail in Il tuo nome è una promessa: the same country that saved her from the Holocaust, holds her captive for almost 40 years.

There are no extraordinary heroes in my stories, no winners or losers, just excerpts of life described gently. My stories do not presume to establish the truth, I am a writer. The writer does not establish the wrongs of History, but tells what happened at that time. And I narrate it in my own voice.

I do not tell about victims, but about people who stood in the middle of History and how it changed their fate. There is always one constant: piety even for evil.

However, there are recurring topics in all my novels: History, the issues of identity and women’s emancipation».

The protagonists of your novels are all women. Is this just a biographical choice, or is it the result of a socio-political feminist reflection?

«I had time to consider the issue of women’s emancipation over the years. It took me years, I needed to understand and to reconstruct what really happened.

Albania was a country with a strong Islamic character. But following 500 years of the Ottoman Empire, communism arrived. In Rosso come una sposa I write about emancipation in that era, by telling how women became free thanks to communism. And this was true.

In the Ottoman era a woman was worth half of a man, as the Quran reports. While in the holy texts of communism, it was written that men and women were perfectly equal. How could it be reconciled? Simply, making women like men, and everything was solved.

In truth, nothing was solved, because men decided that women had to become something else, yet again. The slogan was “woman as an active force equal with man”, but not vice versa. Men did not have to do anything, only women had to adapt to their model, to become the New Man.

With the fall of the communist regime, things changed again. I don’t follow the current situation in Albania so much, I have been missing for almost 30 years. But from a distance, I notice a not so positive change. And I am not talking about the life in Tirana and the new rich, but the rural populations.

But in both contexts, women still have to undergo changes and become something that they have not decided. The new world comes and make them still something else».

Which character in your novels are you most fond of?

«I am fond of almost all my characters. In fact, I would be quicker to mention which one I find repulsive.

I am talking about the character of Enver in Il tuo nome è una promessa. I wanted to tell that dictatorships or circumstances can only make people worse, but not transform them. Because there are characters who remain upright at the cost of death, like Zlatan in L’amore e gli stracci del tempo.

All your novels have been published in Italian. What is the reason of this choice?

«I write only in Italian, and I would not start the reflection from the idiom, but from the word ‘language’. I quote Herta Muller: “Homeland is language, that is possible only where there is free communication between equals”.

My narrative in my mother tongue would have been totally different. Not because of the idiom, but because of the “language” that Italian gave me.

One fundamental thing happens during a dictatorship: the impoverishment and deformation of language. Nothing is natural, words are rationed and hostile to life, because of dictatorships’ perversions.

I was born and raised in the midst of a dictatorship. If I had started writing in that idiom, my language would have been the one imposed on me. I would have named and described the world through the same language I had known since childhood.

I would not have had a second chance, because it is impossible to learn a new language in the same mother tongue».

Beyond the borders

You are born, raised and graduated in Albania, and for the last 26 years you have being living in Italy. What is your relationship with the two countries?

«I have a resolved relationship with both my countries. On one hand, there is the power of belonging to two different places at the same time, but there is also the danger of not catching what is happening around you.

I don’t live clinging on to the past, I have been working so much on the migration/mobility relationship, memory and storytelling. I can quote the artist Chris Marker, who says in the documentary Sans Soleil: “We don’t remember, we rewrite memory”.

Albania is an effervescent, dynamic country, that has gone from pre-modern to post-modern society, skipping modernity. And this is strongly perceived.

The country and its architectural development are the paradigm of this change. Its identity even in the past was compromised, with all the transitions of history and the dominations. But at least there was a bright side: those passages had the merit of telling Albanian history over the centuries.

Instead, globalization sweeps everything away and makes everyone equal in the name of an equality that does not exist. The uniformity is part of a larger context, that is liquid society, and this is also reflected in cultural identity. As Zygmunt Bauman predicted, in this liquidity there is a fluidization that subjects every reality, and all entities pass from the solid to the liquid state losing their definition.

However, I think that this phenomenon affects the whole world, as both singular and cultural identities are in crisis. And it has created relationships based on inferiority and superiority between peoples and cultures.

On the other hand, Italy is going through another phase, which affects all Western democracies. I think they are in crisis, for the first time since the end of World War II.

Democratic capitalism created prosperity and growth, along with social and civil rights. Instead, liberalism is in great pain right now, along with dead socialism. It is enough to say that a democracy that no longer responds to the needs of voters becomes a non-democracy in the long run».

What do you think about the integration of Albanian community in Italy?

«The Albanian community has had a horizontal integration like no other. Of course, it did not happen in a day, it took 30 years. We cannot make comparisons with the present, so much has changed.

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, a new Europe was being redrawn, and this was not just about geographical borders. Now conflicts and wars have increased. And in any case, beyond all rhetoric, Italy is often left alone to deal with all the flows that by necessity arrive on our shores».

“Beyond the Border of Words”. The theme of borders was chosen for the 2023 edition of the Festival of Literature in Lecce, and you are artistic director since its birth.

«In the 2023 edition we started precisely from the word ‘border’, ignoring its geographical meaning. We considered it not as an insurmountable barrier, but as a territory where we become our own borders moving around, traveling and creating new territories. Tracing a path where boundaries are no longer static, but dynamic.

The “border” is not the line drawn, but the boundary to be crossed, in order to consecrate differences and create a common space of co-existence. I am increasingly convinced that this is the only way to overcome borders».

What new projects are you working on?

«I am writing a new novel. I usually don’t talk while writing, because I change so many things along the way.

I can only say that this time it is an all-Italian novel. Words and soil».

Pit stop. Sittin’ at the BarBalkans

We have reached the end of this piece of road.

Today at our bar, the BarBalkans, we read only Ibrahimi’s novels. And the author herself recommends us what to drink.

«I recommend rakia, which is included in almost all my novels. Rakia is not simply a fruit spirit, this liquid has the magical power to heal everything.

And a house without rakia is no home!»

Let’s continue BarBalkans journey. We will meet again in two weeks, for the 2nd stop of this season.

A big hug and have a good journey!

Your support is essential to realize all that you have read. And even more.

A job well done needs many hours and energy. Also to keep BarBalkans newsletter free for everyone and to make it an increasingly original product, with new ideas, interviews and collaborations.

An independent project like this cannot survive without the support of the readers. For this reason I kindly ask you to consider the possibility of donating:

In any case, BarBalkans newsletter will remain for free. And this will never change, it is a matter of principle. The right to be informed should be granted to anyone who wants and feels this need.

The only difference, for those who will decide to support the project, will be the access to a content reserved for subscribers. The monthly article-podcast on the Yugoslav Wars, to find out what was happening - right in that month - in the Balkans 30 years ago.

A sort of time machine, to deepen a topic that is often mentioned but with too little knowledge.

The preview with highlights is open to everyone - you can find it on Spreaker, Spotify, Apple Podcast and Google Podcast - while the detailed article published every second Wednesday of the month is only for subscribers.